Tackling overweight and obesity in Ecuador : Policies and strategies for prevention

Angélica Ochoa-Avilés is a professor/researcher at the Food Nutrition and Health Unit, Department of Biosciences, Cuenca University, Ecuador.

Gabriela Rivas-Mariño is the coordinator of the National Nutrition and Food Security Unit at the Ecuadorian Ministry of Public Health.

Roosmarijn Verstraeten is an independent nutrition consultant and collaborator at the Department of Food Safety and Food Quality, Ghent University, Belgium.

Child and adolescent nutrition and health

in Ecuador

Food labelling regulations

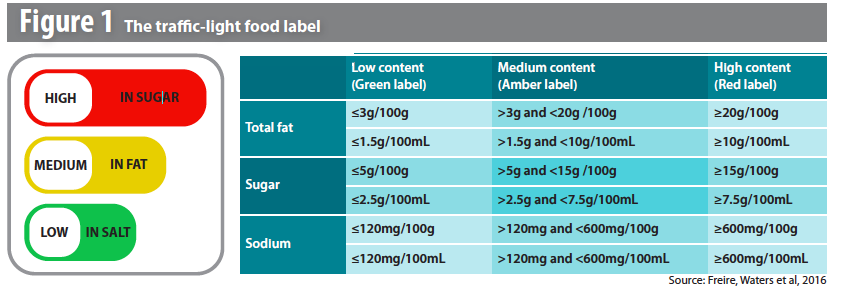

A key policy in the fight against obesity is implementation of traffic-light labelling of processed foods and beverages. This system applies to all the pre-packaged, processed food items containing artificially added fat, sugar or salt, produced nationally or internationally and sold in Ecuador. The labels classify processed food as having a low, medium or high content of total fat, sugars and salt, as described in Figure 1. The label is a simple and useful tool that can help people

choose what they buy and eat. An evaluation showed that children, adolescents concerned about health issues and adult women pay more attention to the label when selecting products (Freire, Waters et al, 2016). Moreover, the population has adjusted eating behaviours in response to a

red label, with reported reductions, for example, in the frequency and amount of consumption of such food items. Instead, people prefer food options with yellow and green labels and natural foods and beverages such as fruits, vegetables and water (Freire, Waters et al, 2016).

Latin American Coalition and the World Cancer Research Fund.

Regulations for in-school food tuck shops

In April 2014, the Ministry of Health (MoH) issued an agreement to regulate the functioning of in-school food tuck shops, which established regulatory committees at national and local level to protect the health of school children. To prevent possible conflicts of interest, the food industry does not form part of these regulatory committees. This is in order to overcome constant industry pressure to block the implementation of the agreement. The regulations prohibit the sale of:

(i) any product with a high sugar, salt or fat content (with a red traffic light); (ii) products containing artificial sweeteners and caffeine; and (iii) energy drinks. In addition, food tuck shops are obliged to sell fruits and vegetables and to offer free, safe water. According to MoH 2016 national reports, 70% of schools comply with the bans relating to red traffic lights and 95% comply with the obligation to sell fruit and vegetables. A more in-depth evaluation of the strategy is planned in 2017.

Physical activity lessons and food taxes

Since 2014, in parallel with the in-school food tuck shop regulations, the Ministry of Education (MoE) stipulated an increase in physical activity lessons from two to five hours per week in the national education system. Unfortunately, neither the results nor an evaluation of this initiative have been reported since its implementation, although the MoH is planning to monitor the initiative in 2017. In May 2015, Ecuador’s National Assembly approved a law to increase taxes on sugary and non-sugary drinks. This fiscal measure imposes a tariff of US$0.18 (18 cents) per 100 grams

of sugar added to processed beverages. For non-sugary drinks, including those that use artificial sweeteners, a rate of 10% of the price is imposed.

Healthy eating and physical activity in

schools: the ACTIVITAL programme

A research group from Cuenca University, in collaboration with researchers from Ghent University in Belgium, implemented the ACTIVITAL programme from 2009 to 2012 to improve dietary and physical activity behaviours among 1,430 school-going Ecuadorian adolescents aged 11-16 years.

The programme involved 20 schools in the urban area of Cuenca, Ecuador’s third-largest city. It consisted of interactive classes taught by schoolteachers on healthy eating and physical activity; participatory workshops with parents and food tuck shop staff on topics such as healthy eating,

physical activity, portion sizes, and food safety; preparation of healthy breakfasts; motivational talks by famous local athletes; and the creation of walking trails in the schools.

the intervention group. The intervention ameliorated the trends towards lower fruit and vegetable intake and less physical activity during adolescence (Ochoa-Avilés, 2015).

• As the programme was not included in the school curriculum, teacher participation was voluntary rather than compulsory, but researchers could not wait for the revised curriculum due to funding constraints;

• Portion sizes of dishes offered by the food tuck shops were large, with high levels of carbohydrates, and low in protein, fruit and vegetables, but there was strong resistance to reducing portion sizes from staff and teachers for cultural reasons and because of the simultaneous initiation of the in-school food tuck shop regulations (described above). A lesson learnt is the

importance of involving all stakeholders in the design, implementation and evaluation of policies to enable the acceptance of feasible and locally adapted strategies.

• Despite recognition of its positive results, ACTIVITAL has not been scaled up due to a national agenda focus that prioritises under 12-year-olds rather than adolescents and the challenge of the MoH and MoE in implementing a joint strategy, since each ministry has different objectives,

frameworks and authorities, and budget issues.

Next steps

Although actions have been taken to promote healthy eating and physical activity, more efforts are needed. Having a national agenda along with a strong political will has helped Ecuador put in place powerful strategies at the national level, but these achievements need protection by: (i) ‘scaling up’

the regulations into laws; (ii) reinforcing the surveillance and monitoring systems for the regulations; (iii) scaling up local, successful interventions; and (iv) increasing the national budget for health promotion.

References

Freire WB, Belmont P, Mendieta M, Silva M, Romero N, Sáenz K, Piñeiros P, Gómez L, Monge R. Resumen Ejecutivo Tomo I. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición del Ecuador. In: Ministerio de Salud Pública INdEyC, editor. Quito, Ecuador, 2013.

Freire WB, Waters WF, Rivas-Mariño G, Nguyen T, Rivas P. A qualitative study of consumer perceptions and use of traffic light food labelling in Ecuador. Public Health Nutrition. 2016:1-9.

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Presentación Defunciones 2011 Ecuador. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos; 2011 (updated 07/01/2013.)

Ochoa-Avilés AM. Cardiovascular risk factors among Ecuadorian adolescents: a school-based health promotion intervention. Ghent University, 2015.