Poshan Nanglo: Piloting a new tool for nutrition behaviour change in Nepal

Sophiya Uprety is a public health nutritionist with 12 years’ experience in Nepal, contributing to nutrition policy and programmes. As a Nutrition Officer for UNICEF Nepal, she was involved in nutrition interventions for recovery from the 2015 earthquake.

Stanley Chitekwe is the Chief of Nutrition for UNICEF Nepal. He has more than 17 years’ experience working with UNICEF in Africa and now in South Asia.

Introduction

Nepal was hit by a devastating earthquake measuring 7.4 on the Richter scale in April 2015 and the government declared 14 out of 75 districts severely affected. As part of emergency response and recovery, comprehensive nutrition interventions including infant and young child feeding (IYCF) and treatment of moderate and severe acute malnutrition and micronutrient supplementation are being implemented in the 14 severely affected districts. The recovery activities are set to continue into 2018.

Child undernutrition is a prevailing issue in Nepal, with rampant inequities. Although some progress has been made in reducing stunting prevalence among children under five years old (stunting has decreased from 49 percent in 2006 to 37 per cent in 2014), it remains high, while wasting rates have stagnated at 11 per cent (2014) (GNR 2017). The inequity is most visible in the mid and far-west regions of the country, especially among disadvantaged dalit and terai caste groups, among the lowest wealth quintile, and among those children whose mothers either have no education or are educated to primary level only.

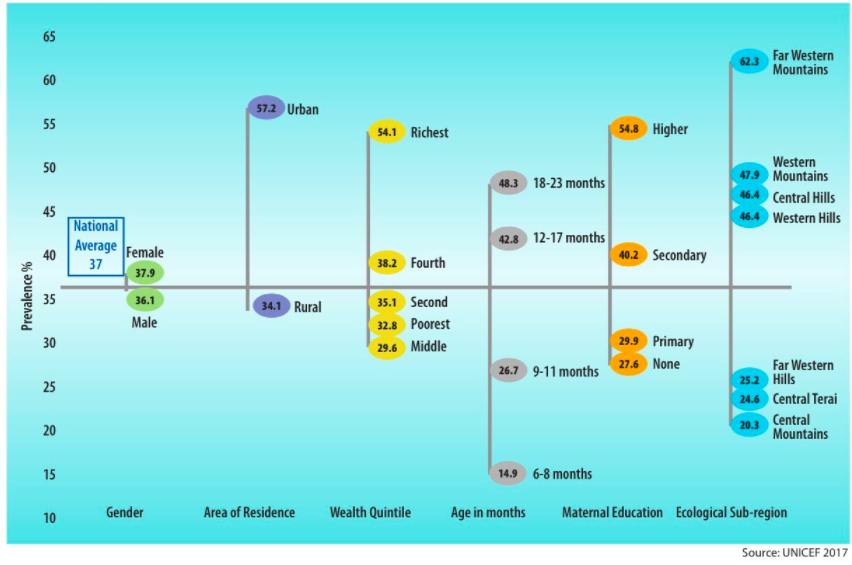

Figure 1: Minimum Dietary Diversity of children aged 6-23 months and Inequity (NMICS 2014)

Optimal IYCF practices, one of the key underlying determinants of child undernutrition, remains a challenge, with wide disparities (see Figure 1). At present, only 37 percent of children aged 6-23 months receive a minimum acceptable diet (GNR 2017).

Behaviour change communication (BCC) is an important IYCF promotion strategy and there is an urgent need to explore innovative, complementary approaches to improving IYCF and to test their feasibility, as well as their effectiveness for scaling-up.

Display of local foods

Poshan Nanglo (‘tray of food’) is a display of seven complementary food groups that are locally available. These are presented by female community health volunteers (FCHVs) in a nanglo, a traditional flat, round, bamboo tray widely used in Nepali kitchens. Nutrition workshops and trainings in Nepal are often accompanied by an attractive display of foods at the venue, an approach adapted for the community level. The same concept was used to encourage the display of seven food groups (grains, roots and tubers; legumes and nuts; dairy products; meat and fish products; eggs; vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; other fruits and vegetables) for IYCF counselling. Using the nanglo, a common item used by all strata of society, for arranging the food display is thought to help associations with food at the household level. The aim of Poshan Nanglo is to reinforce minimum dietary diversity in line with the standardised IYCF promotion slogan ‘harek bar khana char’ (‘consume at least four out of the seven food groups in every meal’). Poshan Nanglo displays were implemented as part of the BCC component of the Nutrition Week campaign, an extension of the well established national vitamin A campaign, in the 14 severely earthquake affected districts (INEHD 2015).

In view of the potential to replicate and scale up the approach, the tool was piloted in three districts of Kathmandu Valley to test its acceptability by the FCHVs and to understand their perception of its effectiveness. Training for the Poshan Nanglo display was integrated with the refresher trainings for the FCHVs that took place prior to Nutrition Week in 2016. FCHVs provided the nanglo and the foods displayed, hence there was no additional cost involved with the implementation. Data collected on its use (63 FCHVs were purposively selected from urban, periurban and rural areas) aimed to evaluate whether this tool was more effective than other educational materials, such as flipcharts for nutrition BCC.

Key findings

FCHVs found the Poshan Nanglo display of real food to be more effective for counselling than flip-chart pictures for a number of reasons:

• Display materials were easily available (foods can be tailored to local contexts and seasonality);

• Mothers appeared more interested and listened carefully (this may be due to the multi-sensory learning experience of being able to ‘see and touch’ real food as opposed to looking at pictures);

• Easier to show and explain the ingredients used in preparation of nutritious complementary foods, such as sarbottam pitho lito and jaulo (used to make porridge);

• Easier to counsel on the use of Baal Vita (multiple micronutrient powders (MNPs)), since it is recommended to add the powders to the porridge.

Poshan Nanglo also breaks the literacy barrier for both promoters and beneficiaries as it does not require the ability to read. Furthermore, it brings supplementation as well as food-based approaches together and promotes both at the same time. Integration with the vitamin A supplementation programme provides opportunity for counselling on utilisation of MNPs. Poshan Nanglo also gives visibility to the role of food, thereby facilitating agriculture-nutrition linkages and helping to promote the concept of household food production. Such food displays are equally relevant in rural as well as urban areas, since they can even help to encourage the mothers/caretakers to increase dietary diversity. For example, rural households with livestock such as cows, buffalo and chickens can be encouraged to prioritise milk and milk products and eggs for children. They can also help address not just undernutrition but increasing problems of overweight/ obesity since they help sensitise people to ‘real’ nutritious foods rather that packaged foods high in calories that are increasingly found to be given to children, especially in urban areas.

This is a low or even ‘no-cost’ intervention, since orientation of the concept was integrated into existing trainings and display items were provided by the volunteers themselves (an estimate for the cost of the two-hour orientation and food cost is approximately US$5 per FCHV). The plan is to maintain this approach for scale-up.

Some challenges

Displays of perishable foods, especially dairy and meat products, were prone to deterioration during long campaign hours. Similarly, the FCHVs were faced with a dilemma when children played with the displayed foods and sometimes even wanted to eat items like fruits, which affected the comprehensiveness and arrangement of the display.

Another potential challenge is that some households might not be able to afford all the foods in the display, but care was taken to ensure that the Poshan Nanglos contained foods commonly found in the different communities and even in the households.

The pilot study only presented the perspectives of the FCHVs and the viewpoints of the mothers and caretakers have yet to be understood. Data collection was completed one and a half months after the intervention and there is therefore some possibility of respondent recall bias.

Next steps

There is a strong network of more than 50,000 FCHVs across Nepal who are government-funded and trained. The uptake of the tool by FCHVs in Kathmandu Valley and positive perceptions of the FCHVs sampled indicate the potential for a wider coverage and impact of this simple, homegrown solution on IYCF to strengthen nutrition BCC efforts. The next step would be to conduct a more robustly designed evaluation to measure the impact on IYCF knowledge, attitude and practices of mother/caretakers, as well as include beneficiaries’ perspectives on the Poshan Nanglo itself as a BCC tool.

In addition to the nutrition campaign, there is potential to include Poshan Nanglo in other existing platforms, such as mothers’ group meetings convened by the FCHVs on a monthly basis. Participants could be gradually encouraged to contribute food items and jointly organise cooking demonstrations of complementary foods. UNICEF is currently working to support the scaling-up of the concept as part of Multi-sector Nutrition Plan II in 28 of the 75 districts.

References

GNR 2017. Global Nutrition Report (2017) Nutrition Country Profiles: Nepal.

INEHD (2015). Cost-effectiveness Analysis of CNW for Emergency Nutrition Response in Earthquake Affected Districts in Nepal.