Improving social protection programmes to support mothers and young children’s diets in Bangladesh: Combining cash transfers with behaviour change

The Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, Government of Bangladesh, provided information and editorial support for this article.

Dr Md Shah Nawaz is the former Director General of the Bangladesh National Nutrition Council.

Masing Newar is the Programme Policy Officer for the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

Colleen O’Connor is the Nutrition Officer for the World Food Programme in Bangladesh.

Background

Bangladesh has made strides in improving health and nutrition in recent decades, yet it still faces challenges in reducing undernutrition, including micronutrient malnutrition. The prevalence of stunting in children under five years old decreased from 47% in 2007 to 28% in 2019 and the country is on course to meet the global targets for both child stunting and overweight, although the prevalence of wasting is 9.8% is higher than the regional average of 8%1.

Young children’s diets and feeding practices in Bangladesh are very poor. Recent analysis found that only 28% of breastfed children and 17% of non-breastfed children aged 6-23 months achieve a minimum acceptable diet. This is mostly due to low dietary diversity and is most evident in the poorer sectors of society1. Ending such wealth inequities is behind the growing focus on social protection programmes as part of a multi-system approach to improving young children’s diets and feeding practices amongst the most vulnerable. The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) is also seeking to streamline social security programmes and life-cycle risks, including early childhood needs, through the National Social Security Strategy (NSSS).

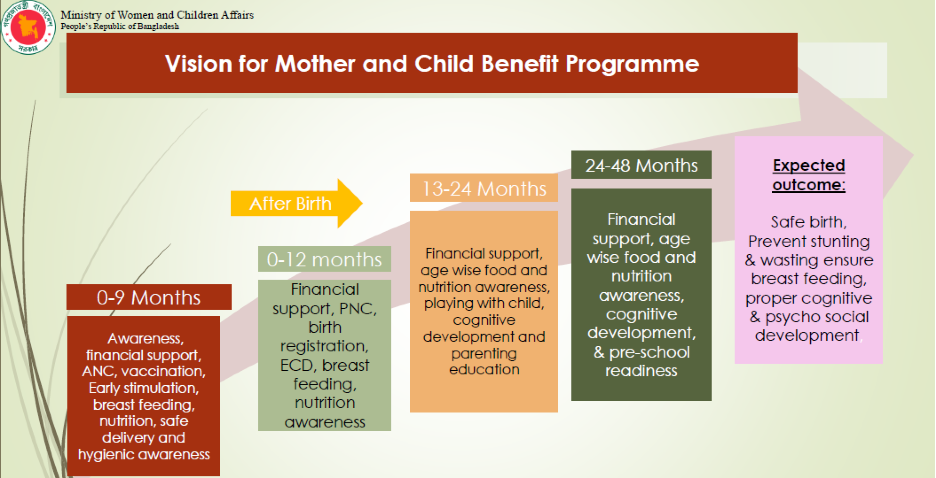

This article explores the GoB’s new Mother and Child Benefit Programme (MCBP) and its potential contribution to improving nutrition; in particular the diets of infants and young children and vulnerable young mothers. Comprised of two existing social safety net programmes and including new components, the MCBP seeks to address nutritional vulnerability by prioritising support to infants and young children aged 0-4 years and their mothers.

Women attending a Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) session on nutrition as part of the Mother and Child Benefit Programme (MCBP). © WFP/MehediRahman

Women attending a Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) session on nutrition as part of the Mother and Child Benefit Programme (MCBP). © WFP/MehediRahman

Enhancing the evidence base for action

A Fill the Nutrient Gap (FNG) analysis was conducted by the GoB’s Cabinet Division with support from the World Food Programme (WFP) in 2019 to assess the barriers faced by the most vulnerable to accessing and consuming healthy and nutritious diets in Bangladesh2. A lack of knowledge amongst household members on infant and young child feeding (IYCF), as well as limited decision-making power and mobility for women and adolescent girls, were found to be key barriers to achieving a minimum acceptable diet, in addition to financial barriers2. It was also found that the cost of a nutritious diet in Bangladesh is over twice that of an energy-only diet. Children from the poorest households are twice as likely to be stunted as children from the richest households3. Added to this, recent evidence showed that combining behaviour change communication (BCC) with cash transfers (CT) resulted in greater reductions in childhood stunting than CT alone in Bangladesh4. The findings from these key studies led to the design of new components and changes in the MCBP.

One of the policy recommendations resulting from the FNG analysis was that “transfer values for social protection need to be almost doubled to enable positive nutrition outcomes for all pregnant and lactating women and young girls”, as this can have a direct impact on the health and nutrition of young children through the life-cycle approach. Currently 13% of households in Bangladesh are unable to afford a nutritious diet, assuming optimal choices are made. Social protection programmes such as the MCBP could reduce the percentage of households unable to afford a nutritious diet by up to 50% (assuming optimal food choices). Providing micronutrient supplements or fortified rice could add to this reduction.

Early social protection programmes

Bangladesh has various social safety net programmes targeted at reducing vulnerability, poverty and inequalities for a range of population groups. The rural-based Maternal Allowance (MA) and the urban-based Lactating Mother Allowance (LMA) programmes, both under the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs (MoWCA), targeted poor pregnant women who were admitted to the programme based on set criteria5. The MA and LMA aimed to reduce maternal and infant mortality, increase rates of breastfeeding, and increase utilisation of delivery and prenatal care services by providing improved linkages between services, as well as BCC sessions, which were run by a resource pool of frontline staff from various ministries. The BCC sessions are reported to have encouraged greater coordination and cooperation between the different ministries involved (health, education, and women and children’s affairs) at both national and sub-national levels.

Nearly one million women were selected by MoWCA and enrolled yearly each July (the start of the financial year in Bangladesh), so only women pregnant at that time could be admitted to the programme. They received a monthly cash transfer of about USD 6 (500 Bangladeshi taka (BDT) for 24 months. The women could only participate and receive the allowance once, for either their first or second live birth.

The pregnant women directly receiving the monthly stipend were encouraged to spend it on a nutritious diet for themselves and thereby contribute to the health of their unborn child. After the child’s birth, the money was intended to cater to the nutritional requirements of the mother, then later for age-appropriate complementary foods for the child.

Moving forward with a new programme

The MCBP was introduced in July 2019 and implemented by MoWCA with technical assistance from WFP. It combines the previous MA and LMA and introduces new programme components based on the research outlined above, as well as prior programme evaluations and monitoring visits. The core components of the programmes – monthly CT and BCC – have been retained and are accompanied now by nutrition training, improved linkages to health services and a new child benefit programme.

The MCBP aims to reach 7.5 million children 0-4 years of age by 2030 all over the country with the aim of achieving safe births; preventing stunting and wasting; and ensuring breast-feeding, optimal complementary feeding and proper cognitive and psychosocial development of young children. This will be measured through MoWCA’s monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system, as well as through the effectiveness of BCC modules and a research study to be conducted by an external international organisation.

Figure 1: Vision for the Mother and Child Benefit Programme

Piloting new approaches to improve MCBP impact on young children’s diets

A piloted approach has been adopted in eight upazilas (administrative regions) in both urban and rural areas.

BCC sessions are no longer exclusively for programme participants are now open to all pregnant women and mothers of young children, as well as to their immediate families/caregivers (e.g., husbands, mothers-in-law, etc.). Together with technical partners, several training modules are being developed within a comprehensive training framework to deliver age-specific information on health, nutrition and early childhood development.

Tailored messages are delivered over the course of the woman’s pregnancy until the child is four years old. The messages are delivered at BCC courtyard community sessions by government community-resource pool workers, at antenatal care visits in the health facility, and at household visits. For example, a pregnant woman may receive information concerning which micronutrient supplements to take during pregnancy, while new mothers get messages emphasising the importance of breastfeeding and complementary feeding. Once the child has reached six months of age, new messages will be disseminated on age-specific quantities and frequency of complementary feeding, in addition to messages on continued breastfeeding. Further supporting messages on hygiene and responsive feeding are also shared.

Increasing programme access

MCBP has been further improved through the use of a digital self-enrolment process. An eligible woman can now self-enrol on a rolling basis by going to her Union Data Centre (in rural areas) or her municipality office (in urban areas), and so no longer has to wait until each July. Once her data is put into the digital system, it is linked to the Government-to-Person (G2P) payment system, which enables payments to be made on a monthly basis to the individual’s account, effective immediately6. The mother can begin using the CT for nutritious diets immediately. Research indicates that, by receiving regular small monetary transfers, a household is more likely to invest in better diet, rather than in a large purchase of assets or investments, as is the case when a lump-sum payment is received5. The monthly transfer value is currently about USD 9 (800 BDT).

Challenges and lessons learned

While the new programme has addressed many shortcomings of its forerunners, some challenges persist in its early stages. The MCBP’s digital information system is not integrated with other digital systems, such as those run by the Ministry of Health, which collects children’s health information from birth onward. The Union Data Centres where women enrol are often located far from where the women live and lack reliable electricity and connectivity, necessary for enrolment. This can result in multiple trips to centres for the women, which can be costly as well as physically demanding.

Moreover, the centres are currently independent operators and are not held accountable for the accuracy of their data inputs, often resulting in incorrect data entry. As a result, a high number of CTs have bounced back due to incorrect or mismatching information. While the first transfers functioned well, subsequent transfers faced operational challenges and were delayed.

CTs are not always spent only on food, but also on health, education, farming and business investments, as well as debt repayment. The assumption that small and regular CTs will lead to better diets is challenged, given the low decision-making authority of women in Bangladesh.

The next steps for the MCBP pilots include establishing a comprehensive M&E framework and a formal grievance mechanism, as per the recommendations of a review, before the programme is rolled out nationwide.

Footnotes

1Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). 2019. Progotir Pathey, Bangladesh Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Key Findings. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS).

2Fill the Nutrient Gap Bangladesh – Concise Report (2019). Cabinet Division, Government of Bangladesh, in collaboration with WFP.

3James P Grant School of Public Health and National Nutrition Services. (2016). State of food security and nutrition in Bangladesh 2015. Dhaka, Bangladesh: James P Grant School of Public Health and National Nutrition Services.

4National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), and ICF. 2019. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18: Key Indicators. Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, and ICF.

5Akhter U. Ahmed et al (2016) in collaboration with data analysis and technical assistance International Food Policy Research Institute, WFP. Which kinds of social safety net transfers work best for the ultra poor in Bangladesh?: Operation and impacts of the transfer modality research initiative. Dhaka: International Food Policy Research Institute: World Food Programme, Bangladesh, 2016.

6Although the MA and LMA projects were designed to transfer the allowance monthly, in reality it was done quarterly and, in some cases, annually.