Leveraging the power of multiple systems to improve diets and feeding practices in early life in South Asia

Zivai Murira is the Nutrition Specialist at UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, based in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Harriet Torlesse is the Regional Nutrition Advisor at UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, based in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The day a baby takes his or her first bite of food is a celebrated milestone. It marks the end of dependence on a mother’s breastmilk alone, and a new phase of discovery – new tastes, textures, and smells. Every bite provides additional nutrients to fuel the growth and development of a child’s brain and other vital organs. And every meal is an opportunity for caregivers to give loving, nurturing care.

It can also be an anxious time for caregivers. How much food to give? How many times a day? Which foods are nutritious and safe? These are questions that many caregivers experience. But these issues are compounded many times over for the millions of families in the region who lack the know-how and resources needed to feed their children in the best way possible.

We know there is an immense problem with the diets of young children in South Asia because over half of the world’s wasted children and 40% of the world’s stunted children under the age of five years live in the region1. While diarrhoea and other diseases also cause undernutrition, it is clear that poor diets and feeding practices play a major role. In fact, research has shown that children in South Asia are more likely to be stunted and wasted if they begin complementary foods too late, consume too few meals and lack dietary diversity2.

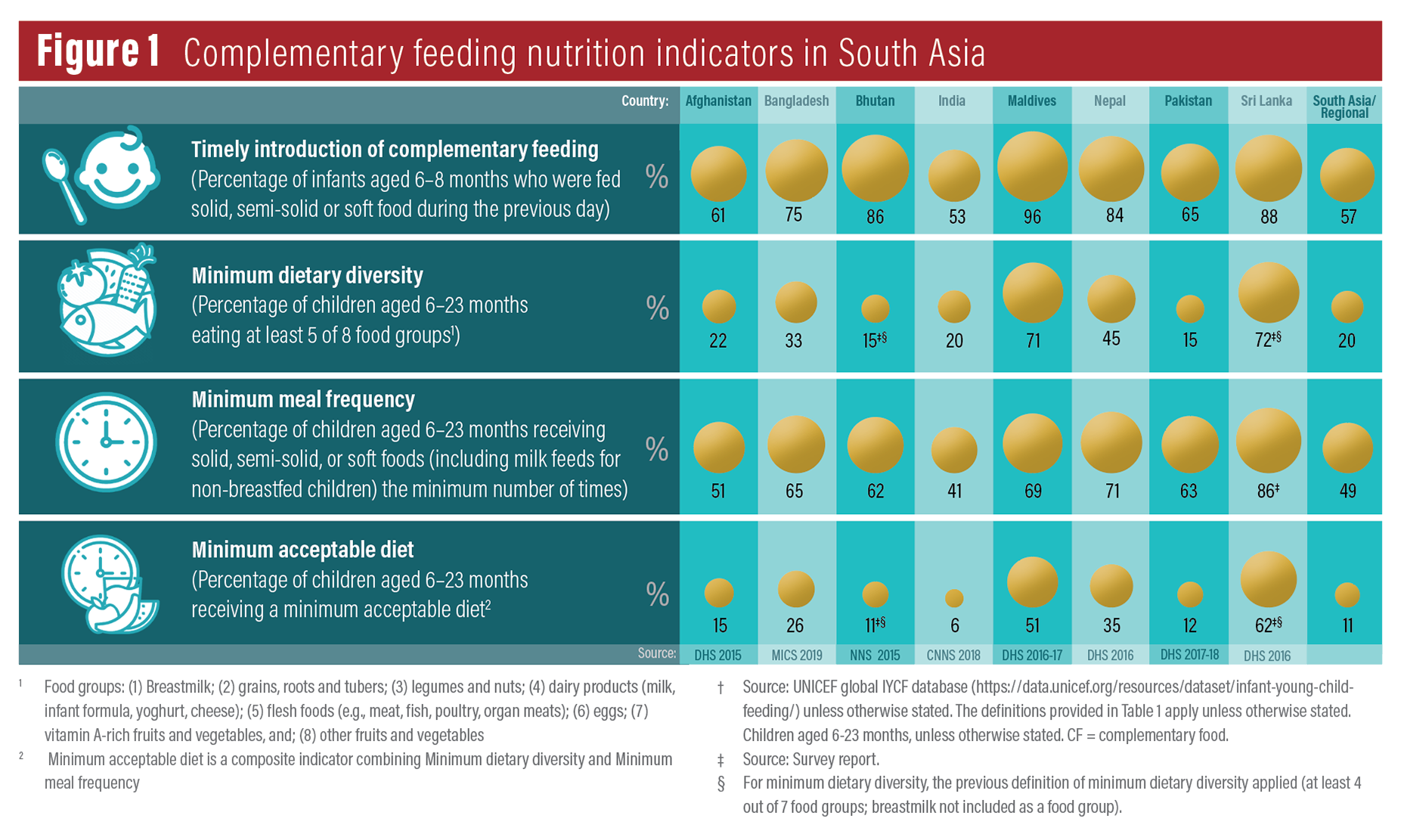

Complementary feeding needs to start at six months of age, but 40% of infants in South Asia are not receiving these foods at age six to eight months. Added to this, an estimated 80% of children aged 6-23 months consume diets that contain less than the minimum of five recommended food groups and 60% are given too few meals per day3. The consumption rate of nutrient-dense foods is particularly low. Only 25% children aged 6-23 months are fed meat, poultry or fish, and only 45% are given any fruits or vegetables4. The diversity of children’s diets is narrower in poorer households; a sign of the income constraints they face5. Continued breastfeeding is still the social norm in South Asia, and the region has higher rates at one year old (82%) and two years old (70%) than any other region in the world3. However, South Asia lags behind other regions on all other aspects of complementary feeding.

New challenges are also emerging. With the growing influence of the food and beverages industry in driving consumer preferences in the region, there are reports of alarming increases in the consumption of unhealthy foods and beverages in early childhood. These unhealthy diets are not only associated with an increased risk of overweight and related health problems in later life: a recent study in Nepal found that young children who frequently consume unhealthy foods and beverages are more likely to be stunted – possibly because these foods are displacing more nutritious foods from their diets5.

To find solutions to the challenges that families face in feeding their young children, we must better understand the drivers and determinants of poor diets and feeding practices in South Asia. These are complex and inter-related and vary considerably across and within countries. In the highlands of the Himalayas, snow can cut off communities from fresh foods for months every winter, while in urban areas, some families are turning to the convenience of unhealthy processed foods. New parents across the region are often surrounded by a cacophony of well-meaning advice on how to feed their young children, often from elder family members who may be more influenced by enduring sociocultural beliefs and taboos. The poorest families simply cannot afford to make the nutritious food choices that health workers advise them will benefit their children. And young children often lose precious nutrients to infections when foods are prepared, stored and fed under poor water, sanitary and hygiene conditions.

Our approach to these myriad problems has often been too narrow, fragmented and disconnected. For example, while the health system has led in educating and counselling caregivers on complementary foods and feeding practices, agricultural policies are too focused on grains and give insufficient attention to crop diversification, while social safety nets are failing to provide the lifeline that many poor households need to purchase nutritious food.

We must rethink how we conceptualise, design and implement programmes in order to improve the access to and consumption of nutritious, safe, affordable and sustainable diets for children in early life. And this is needed now, more than ever. The Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted the lives and livelihoods of millions across the region, as governments strive to halt the transmission of the virus. Job and income losses, rising food prices, constrained physical access to food markets and widespread disruption of health and nutrition services means that poor households face immense difficulties in feeding their family members, including young children.

As we work to respond to these pressing needs both during and in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is imperative that we use this opportunity to reimagine public policy and build stronger systems to meet children’s nutrition needs in early life.

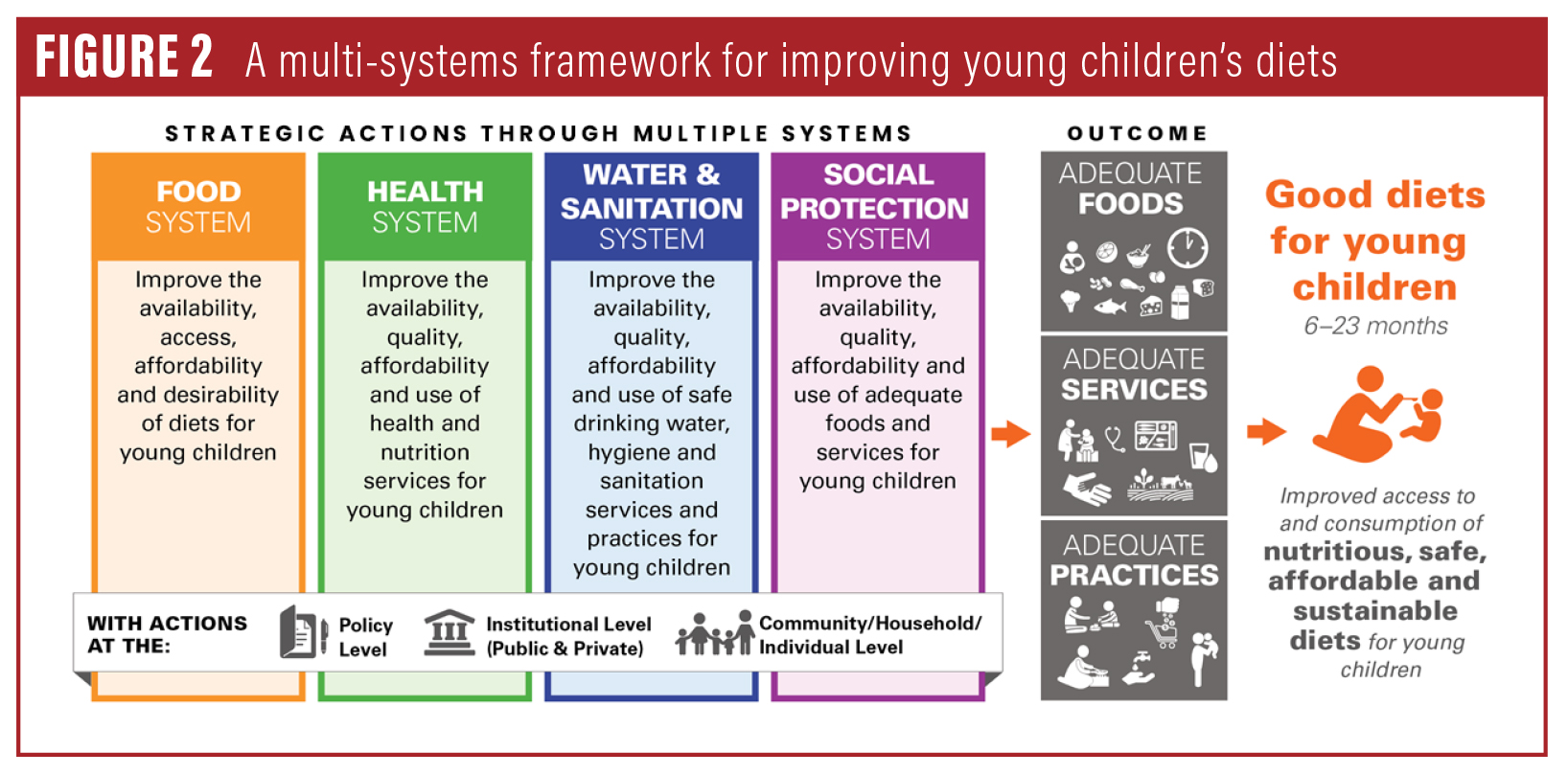

This work is already underway in South Asia. A regional conference was organised by the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) on ‘Stop Stunting | Improving Young Children’s Diets in South Asia’ in September 2019 in Kathmandu, Nepal to galvanise regional and country action to accelerate efforts in improving diets and feeding practices in the region. SAARC member states agreed that no single system or stakeholder group can address all the barriers to optimal diets and feeding. Instead, the collective actions of multiple systems (notably the food, health, water and sanitation, and social protection systems) and stakeholders (government, development partners, academics and the private sector, as well as communities, households and individuals) are required (see Figure 1).

Led by government, these systems and stakeholder groups should work together to:

- increase the availability, access, affordability and desirability of food (‘adequate food’);

- increase the availability, quality and use of services in health and nutrition, social protection, and water and sanitation (‘adequate services’); and

- improve feeding, care and hygiene practices (‘adequate practices’).

It is proposed that every country in the region identifies and prioritises a set of strategic actions across each key system, based on a situational analysis of the barriers, bottlenecks and enablers to achieving adequate food, services and practices to support optimal diets and feeding practices in early life. These strategic actions may vary by context and may be needed across three intervention levels: policy; institutional; and community, household and individual. These These actions should be integrated into multi-sector and sector plans, with resources focused first on the most deprived geographies and population groups, and scaled up in a phased manner.

The Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath risk undoing the progress that has been made across the region to improve nutrition. It is crucial that we build systems that are resilient to shocks so the rights of young children to adequate food and care are protected at all times, especially when they are most vulnerable. We must ensure that children do not carry the scars of poor diets and feeding practices in early childhood for the rest of their lives.

Adapted from UNICEF (2020). Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period. ©UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

Adapted from UNICEF (2020). Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period. ©UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

Footnotes

1UNICEF, WHO, & IBRD/WB (2020). Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: Key Findings of the 2019 Edition of the Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. New York, Geneva, Washington DC.

2Torlesse, H. & Aguayo, V. M. (2018). Aiming higher for maternal and child nutrition in South Asia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(Suppl 4) e12739. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12739.

3UNICEF (2020a). UNICEF’s expanded database on infant and young child feeding. https://data.unicef.org/resources/dataset/infant-young-child-feeding/

4UNICEF (2019). The State of the World’s Children 2019. Children, Food and Nutrition: Growing well in a changing world. UNICEF, New York.

5Pries, A. M., Rehman, A. M., Filteau, S., et al. (2019). Unhealthy snack food and beverage consumption is associated with lower dietary adequacy and length-for-age z-scores among 12–23-month-olds in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. The Journal of Nutrition, nxz140. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz140.