Using an in-depth assessment of young children’s diets to develop a Multisectoral Nutrition Communications Strategy in Punjab province, Pakistan

Dr Muhammad Nasir is a medical doctor and Programme Manager in the Primary and Secondary Healthcare Departments of the Government of Punjab.

Eric Alain Ategbo (PhD Nutrition) is Chief, Nutrition, UNICEF, Pakistan.

Dr Saba Shuja is a medical doctor and Nutrition Officer with UNICEF, Pakistan.

Dr Wisal Khan is a medical doctor and Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF, Pakistan.

Dr Shafiq Rehman is a medical doctor and Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Pakistan.

Background

Pakistan’s most recent National Nutrition Survey (NNS 2018) identifies worrying levels of child malnutrition. The national prevalence of stunting in children under five years old is approximately 40% and wasting prevalence is nearly 18%1. Poor complementary feeding practices among children aged 6-23 months is reported to be one of the main causes of undernutrition, particularly stunting in the South Asia region. Research has shown that children in South Asia are more likely to be stunted if there is delayed introduction of complementary foods, a young child’s diet is low in diversity, and a child is given too few meals2.

Between Pakistan’s NNS in 2011 and 2018, there was a decline in three of the four complementary feeding indicators, which is likely to be due to a combination of factors: ongoing economic limitations within households, feeding and caregiving constraints and an increase in the marketing and availability of low quality ‘junk’ foods. Only one in seven children (14%) aged 6-23 months receive a meal with minimum dietary diversity (at least four different food groups); one in four children (18%) receives the minimum number of meals per day; and less than one in 20 children (about 4%) are provided with complementary foods that meet the requirements of a minimum acceptable diet for children aged 6-23 months1. Although a greater proportion of children receive adequate complementary foods in urban areas, the situation is very poor in both urban and rural localities underscoring the need for significant improvement in the diets of young children across the entire country1.

Infant and Young Child Feeding counselling session in Lahore, Punjab province. ©UNICEF/Pakistan/Zaidi

Filling the ‘information gap’ on complementary feeding in Pakistan

Pakistan’s Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) strategy (2016-2020) when formulated in 2015, lacked an evidenced social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) component and in particular, a good understanding of complementary feeding. This gap triggered a National Complementary Feeding Assessment (NCFA) to generate evidence around beliefs and behaviours and to better understand the enablers of and barriers to optimal feeding practices across the various provinces. The NCFA also looked at the decision-making processes in households with regards to infant and young child food choices. Added to this, IYCF counselling, while part of many nutrition programmes in Pakistan, has been low in coverage and of poor quality. Understanding the reasons for these challenges is necessary if barriers are to be overcome.

The Government of Pakistan conducted the NCFA between 2017 and 2018 to provide, for the first time, in-depth information needed to strengthen its IYCF approach. Specifically, the NCFA comprised:

- In-depth secondary analysis of data on complementary feeding practices from the Pakistan Demographic Health Survey (2013-14);

- Formative qualitative research on complementary feeding behaviours and practices; and

- Cost of Diet and Optifood Dietary Analysis3 to analyse the cost of a nutritious diet.

This article describes the findings of the NCFA, and the experiences and lessons learned in strategically using this evidence to influence the development of a Multisectoral Nutrition Communications Strategy in Punjab province, Pakistan.

Key findings from the NCFA

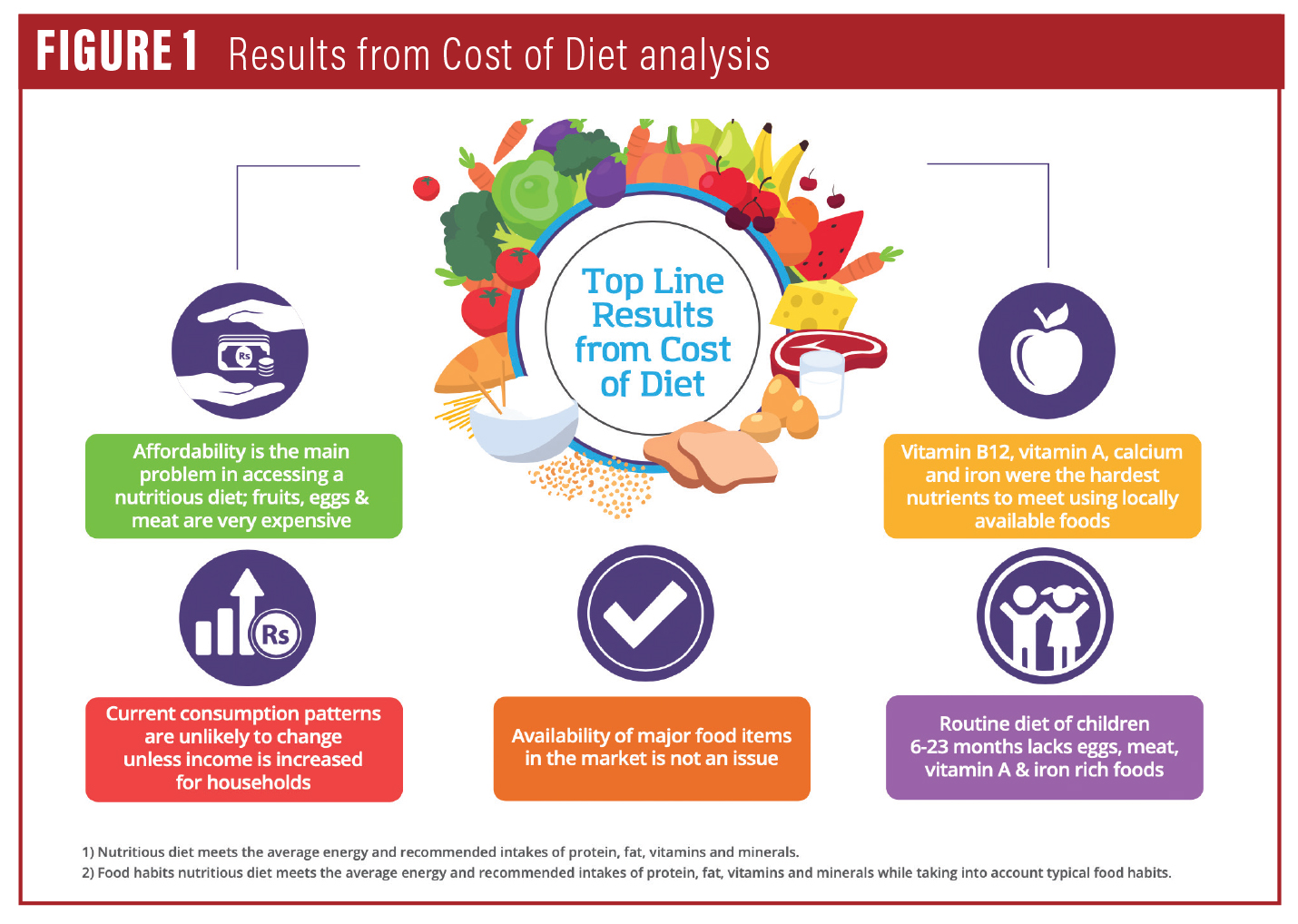

The NCFA highlighted that affordability is the main problem in accessing nutritious foods during the complementary feeding period, notably fruits, eggs and meat, which are all very expensive. Despite affordability issues, mothers and caregivers are believed to prefer more expensive but convenient foods such as infant cereals, which are perceived to be more nutritious. Added to this, households are known to sell more nutritious foods such as eggs and milk from their own produce to obtain cash and can use this cash to purchase complementary foods. Availability of the main food items in local markets was found not to be a barrier, except in difficult geographical terrains such as mountainous regions where geographical access was constrained.

Most children aged 6-23 months are fed the same food as the rest of the family; thus family eating behaviours influence the diets of young children. The caregiver’s dietary preferences also restrict the consumption of some nutritionally rich and less expensive foods, such as millet, which is widely perceived as ‘bird food’. Meanwhile, the consumption of unhealthy processed foods (such as chips; papar (a local snack food); and biscuits) is common among young children, suggesting that caregivers consider these foods an acceptable component of young children’s diets.

The NCFA also identified a lack of knowledge on dietary diversity among healthcare providers, whom, along with grandmothers and fathers, were found to be important influencers of complementary feeding practices.

Dietary analysis

The Optifood Dietary Analysis identified vitamin A, iron, zinc, folate (for children aged 12-23 months) and calcium to be important ‘problem’ nutrients, along with vitamins B1, B3, B6 and B12 (for children aged 12-23 months) and folate (for children aged 6-11 months), which were lesser problem nutrients. The Optifood analysis also showed that the problem nutrients could be largely increased using food-based recommendations (e.g., increased consumption of eggs, roti and milk, as well as home-based fortification), with supplementation needed to address dietary gaps in vitamin A, iron and zinc.

Figure 1: Results from Cost of Diet analysis

Designing a context-specific communications strategy for Punjab province

Additional analysis was conducted to provide region-specific information on key barriers, enablers and influencers of feeding practices in Punjab province. The findings were used by the Multi-Sectoral Nutrition Centre (MSNC), housed in the Planning and Development Department of the Government of Punjab, to support its Multisectoral Nutrition Communications Strategy to improve complementary foods and feeding practices. This information was synthesised into priority themes for programme actions and key messages for communication approaches, with an emphasis on effective, context-specific SBCC interventions. The MSNC, in collaboration with the provincial health department and UNICEF, developed a Communication Messages booklet on nutrition for frontline workers and communities, which acts as a resource to support positive and sustained behaviour change in key nutrition practices.

Under the leadership of the provincial government stakeholders, the messages are being delivered through various communication channels, including nutrition education counselling by Lady Health Workers (LHWs)4 with individual mothers, caregivers and their influencers; community engagement by LHWs with mothers’ groups and fathers’ groups; and text messaging, websites and social media platforms, such as Facebook. The Communication Messages booklet is also used a guiding resource by the staff working in health facilities with responsibility for IYCF counselling.

Challenges in converting evidence into action

The findings of the NCFA were well received and accepted by the provincial Department of Health and keen interest was shown by the policy makers and programme planners in using these findings to inform programming. However, translating the evidence from the NCFA into communication actions was the main challenge faced in Punjab. For example, as this was a multi-sector communications strategy, there was high demand from sectors to include a large number of communication messages that are not based on strong evidence.

A prioritisation workshop was organised with relevant stakeholders from each sector and communications experts for a consultative process to decide on which interventions and messages should be prioritised. Areas for joint implementation of activities were then identified (for example, integration of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) messaging on the hygienic preparation of complementary foods as part of IYCF messaging). This process resulted in the formulation of prioritised and harmonised nutrition messages focusing on feeding practices, brought together in the Communication Messages booklet.

Next steps

The qualitative findings of the NCFA will continue to play a crucial role in driving advocacy and behaviour change campaigns on complementary feeding, in other provinces as well as Punjab. The Punjab Multisectoral Nutrition Communications Strategy lays out a potential road map of communication activities and practices that could be adopted and adapted to create a cohesive and sustainable behaviour-change campaign across the country. The findings of the NCFA will also inform the upcoming process of revamping Pakistan’s IYCF communication strategy with clear benchmarks to track the progress of communication efforts in improving the feeding practices of young children.

Footnotes

1National Nutrition Survey (2018) https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/media/1951/file/Final%20Key%20Findings%20Report%202019.pdf

2UNICEF (2020). Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period. UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund.

3Optifood is a software application that allows public health professionals to identify the nutrients people obtain from their local diets, and to formulate and test population-specific food-based recommendations to meet their nutritional needs.

4Lady Health Workers are Pakistan’s cadre of salaried community health workers.