Combining a mid-day meal, health service package and peer support in Karnataka State, India

Combining a mid-day meal, health service package and peer support in Karnataka State, India

Uma Mahadevan is Principal Secretary in the Department of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj. Prior to this she was Principal Secretary, Women & Child Development in the Government of Karnataka.

Vani Sethi is a Nutrition Specialist (adolescent and women’s nutrition) in the Nutrition Division, UNICEF India country office, New Delhi.

Khyati Tiwari is the Nutrition Specialist for UNICEF for the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka.

Arjan de Wagt is Chief of the Nutrition Section, UNICEF India country office, New Delhi.

Background

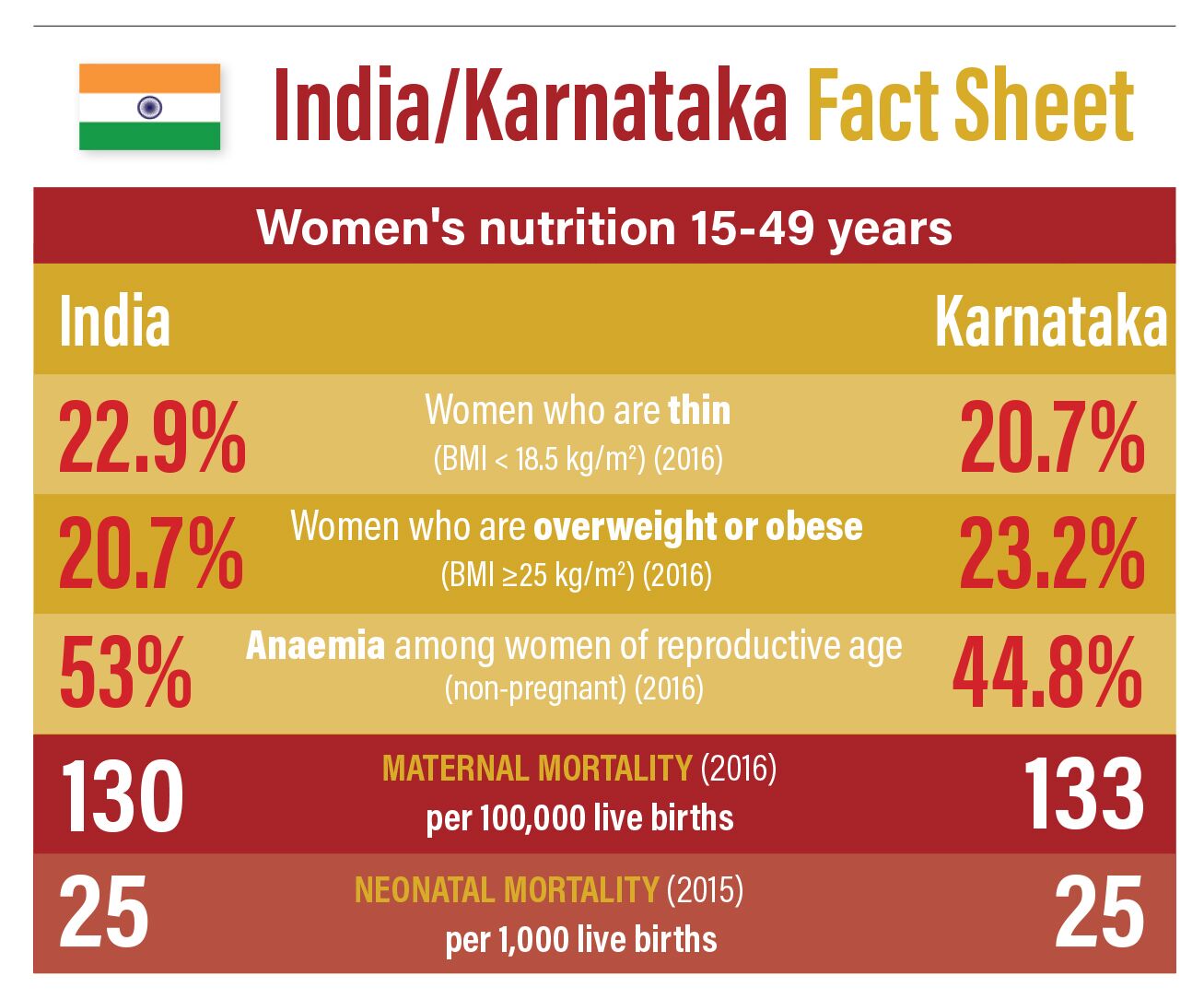

Karnataka is a Southern Indian state with a population of 68.7 million and one of the highest economic growth rates in the country1. Paradoxically, the state continues to have high rates of maternal mortality2; over 21% of women of reproductive age (WRA) are too thin (low body mass index); and 40% of WRA are anaemic3. Karnataka is also the second-largest drought-prone area, with nearly 60% of the state affected by recurring drought each year during the past decade4, aggravating food and water security crises, increasing migration and disrupting routine services. Data shows that the diets of women in the state are deficient in essential nutrients, with low daily consumption of milk, pulses, green leafy vegetables and animal foods4.

Nutrition services for women are delivered largely through the flagship programmes of two state departments: Women and Child Development (WCD), and Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). However, there is evidence that only just over one third of women are receiving the full antenatal package 3. To improve the situation for women in Karnataka, a scheme was launched that focused on layering interventions, including a hot cooked meal, health services and counselling, to deliver maternal nutrition in one platform. This article describes the launch of the Mathrupoorna (‘complete motherhood’) programme in Karnataka and lessons learned for scaling up Karnataka’s nutrition services for women.

The Anganwadi services scheme5 is a nationwide programme with six mandated basic services, which are modified in various states. Every state receives some central government funding for the scheme, but also contributes its own resources. Under the WCD, the Anganwadi services scheme provides a balanced energy protein supplementary food for pregnant and lactating women for 25 days a month. The supplement is intended to provide 600 kilocalories, 18-20 grams of protein and 50% of the recommended dietary allowance of nine essential micronutrients.

The MoHFW aims to deliver a number of interventions to pregnant women via its monthly facility and community outreach antenatal care (ANC) sessions, including: micronutrient supplements (iron and folic acid and calcium); deworming; weight-gain monitoring; medicated mosquito nets (in malaria-prone areas); and counselling.

Integrating services

In spite of these efforts, data shows that just 33% of pregnant women received the full antenatal service package; 45% consumed at least 100 iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets in pregnancy3; and, more encouragingly, 62% of pregnant women received supplementary food3. The challenge faced by the state was universalisation of coverage of the supplementary food services (which was being provided as a dry ration at that time) and combining this with the delivery of health services in one platform.

Such integration had already been accomplished in the neighbouring states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh in programmes that replaced the dry supplementary food with a cooked meal alongside the provision of IFA supplements after the meal under supervised conditions. This ‘one full meal’ scheme had also provided an amalgamated platform of nutrition services (food, micronutrient supplementation, deworming, gestation weight-gain monitoring and fortnightly nutrition health education) to pregnant women, helping reduce the intra-household distribution of the supplementary food and promoting participation in self-help groups. In both states, improvements were observed in reach of counselling and supplementation services6.

Launching the Mathrupoorna scheme

To address the coverage challenges in delivery and uptake of supplementary food services, Mathrupoorna began as a pilot in four districts of Karnataka in order to generate learning to inform scale-up of the programme in the state. An estimated 5,000 women took part in the pilot.

The scheme, which is self-selective, includes a daily mid-day meal to be eaten at the Anganwadi centre by pregnant and lactating women (PLW) at a fixed time (normally between 11 am and 2 pm), for 25 days a month. The meal meets 40-45% of recommended daily caloric, protein and calcium requirements, at a daily cost of INR21 (USD0.3) per person.

After each meal women are administered a supervised dose of IFA or calcium. Counselling sessions on various themes, from diet to health services, entitlements and family planning, are delivered by the Anganwadi worker at least once every two weeks. The platform is also used for gestational weight-gain tracking of each pregnant woman and provision of health services such as blood-pressure monitoring; tetanus toxoid vaccination; deworming and assessing other signs of nutritional and health risks through clinical and anthropometric measures (height, weight, MUAC and clinical signs) once a month as part of four ANC checkups. The Anganwadi worker keeps a record of services received by the women in the programme, their pregnancy weight gain and the weight of their children at birth.

Lessons learned through pilot testing

An evaluation of the pilot scheme helped to identify a number of issues that needed to be addressed before scaling up the programme.

1. Objections to the replacement of the dry take-home ration with the mid-day meal at all levels (village, block, district) resulted in some reluctance to participate in the scheme.

Discontinuing the dry ration was not popular initially with beneficiaries for many reasons, including time constraints and preference for a take-home ration. There were also political reasons to support continuation of this supplement that needed to be addressed by consensus-building at state and district level. Furthermore, the Anganwadi workers and helpers, who are the main implementers in the delivery of the scheme, needed their concerns to be addressed before rolling it out.

2. Institutional and human resource

capacity constraints can limit the roll-out of a complete package of services.

Anganwadi workers at smaller centres without helpers found it challenging to cook the mid-day meals in addition to their other responsibilities. Additional help with meal preparation required an extra INR500 (USD7.2) per month to incentivise helpers.

3. A customised menu was needed to encourage consumption of the cooked meal.

One of the most common reasons women refused a hot cooked meal was the lack of variety in taste. Wide variation in taste preference across the region needed to be addressed, and districts were therefore given the autonomy to modify the menu according to local needs, provided the nutritive value was not affected.

4. Community participation was essential for improving participation in the scheme.

In Karnataka, Balvikas Samithis (child development committees) consisting of representatives from the village already existed within the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS)7. These committees were restructured to include mothers as chairs, and wider membership of PLWs, grandmothers and fathers of children coming to Anganwadis.

The Samithis are responsible for:

• Ensuring demand and supply of food, such as rice, pulses, oil, eggs, chikki8, milk and vegetables at the Anganwadi;

• Supporting Anganwadi workers to mobilise all eligible beneficiaries to attend the centre;

• Ensuring the quality and hygienic preparation of the meals;

• Ensuring the availability of basic services, such as safe drinking water, a toilet etc.

5. Convergence across at least three government departments (WCD, Department of Health (DoH) and the Department of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj) was essential to ensure availability of supplies and services.

WCD issued multiple instructions through government orders for the effective implementation of the Mathrupoorna scheme, such as a joint order with the DoH to ensure the availability of relevant micronutrient supplements at the Anganwadis.

6. Overcoming sociocultural issues and superstitions is important to ensure uptake of the scheme.

Counselling is one of the main tools to address deeply entrenched beliefs regarding nutrition in pregnancy and lactation, caste and wealth-related discrimination. While initially most of the pregnant women would face the walls to eat in order to avoid the ‘evil eye’9, within a few days they had turned around and started eating together facing each other. The state has introduced the Mathrupoorna counselling flipbook to strengthen advice. This covers such topics as the importance of early pregnancy registration, ANC, anaemia prevention and treatment, food taboos and myths and dietary diversity.

Scaling up the scheme

Following review, the scheme has now been scaled up to 65,911 Anganwadi centres and reaches over 629,000 PLWs every month. Programme data comparing the year December 2017 with December 2018 shows that the reach of the Mathrupoorna service package increased by 11% for consumption of at least 100 IFA tablets, 23% for administration of single-dose deworming tablets, 8% for participation in at least two counselling sessions, and 6% for eating one full meal per day for at least 21 days at the Anganwadi centre.

In order to enhance the quality of care and optimise the contact opportunity, a number of new activities have been introduced to assess nutritional status, such as monitoring upper arm circumference (MUAC) and weighing machines for pregnant women and height measurement for children. Supervisors and Anganwadi workers visited the homes of PLWs in slums and migrant communities to encourage this hard-to-reach group to enrol in the programme and thus increase coverage. Provision has now been made for a family member to take the hot cooked meal home in situations when women were advanced in their pregnancy and for the first 45 days following delivery. Meal timings were also adjusted to times that were convenient for the women in the scheme to access, and Anganwadi workers and helpers are now provided with hot meals for their own consumption.

Lessons learned

An external evaluation carried out in March 2019 found the Mathrupoorna scheme was being utilised by the community and awareness levels are fairly high among women being served. While Anganwadi workers were supportive of the scheme, they were also concerned that time spent on it may be detracting from their other activities, such as pre-school education. Many workers were also concerned about food waste, due to uncertainties regarding the demand for meals on the day. The need for additional personnel at Anganwadis to help implement the scheme in order to avoid over-burdening already-busy frontline workers is a key learning point.

Way forward

The Mathrupoorna scheme has emerged as a promising platform for delivering a combination of services to the most disadvantaged. Some challenges remain. These include reducing the burden of frontline workers by engaging more with women’s self-help groups, and maintaining demand and increasing uptake and coverage for the programme.

Footnotes

1http://www.census2011.co.in/census/state/karnataka.html

2www.censusindia.gov.in/vital_statistics/SRS_Bulletins/MMR%20Bulletin-2014-16.pdf

3National Family Health Survey (2015-16)

4Karnataka State Natural Disaster Monitoring Center, 2017. Report of drought assessment in Karnataka.

5An Anganwadi is a type of rural childcare centre in India, which provides basic healthcare in a village.

6http://unicef.in/Uploads/Publications/Resources/pub_doc10151.pdf