Nepal’s success story: What helped to improve maternal anaemia?

Dr Ram Padarath Bichha is Director of the Family Welfare Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal.

Kedar Raj Parajuli is Chief of the Nutrition Section in the Family Welfare Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population, Nepal.

Pradiumna Dahal is a Nutrition Specialist with UNICEF Nepal.

Naveen Paudyal is a Nutrition Officer with UNICEF Nepal.

Stanley Chitekwe is Chief of the Nutrition Section, UNICEF Nepal.

Introduction

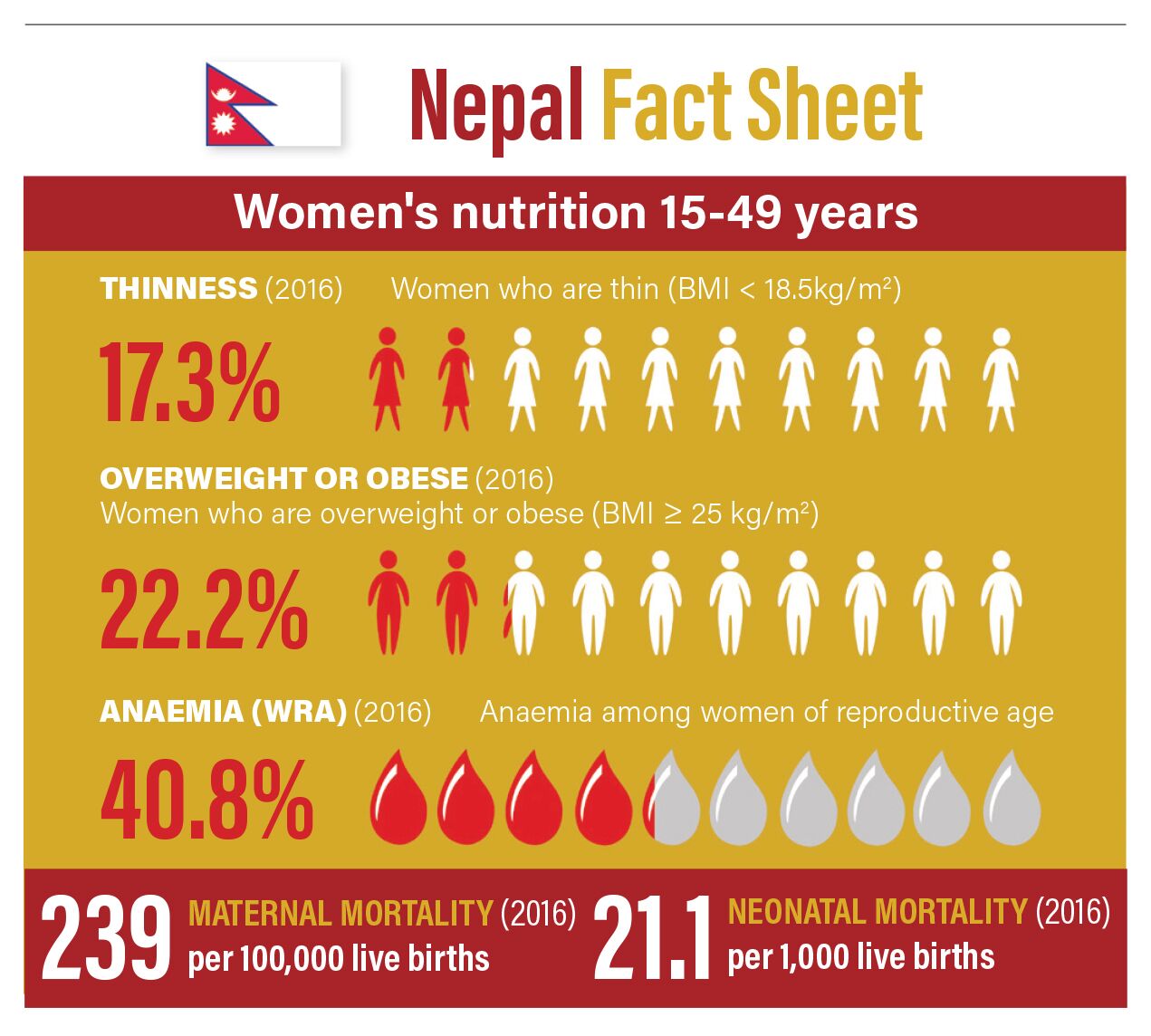

The nutritional wellbeing of women in Nepal remains a challenge. Undernutrition (body mass index <18.5 kg/m2) among women of reproductive age (15-49 years) is declining and currently affects 17%, while prevalence of overweight among women in this age group is steadily increasing and is now at 22%1. Prevalence of anaemia is of moderate public health significance; 20% of non-pregnant women in this age group are anaemic. However, there has been a significant reduction in prevalence of anaemia among pregnant women over the past two decades. In 1998 it was alarmingly high with 75% of pregnant women with anaemia; by 2016 this had decreased to 46% prevalence of anaemia among this same group1.

This article explores Nepal’s success in achieving a significant reduction in maternal anaemia and in the increased uptake of iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation by pregnant women between 2002 and 2016. A number of factors played a role in this story, including government commitment to address the problem, an increase in health facilities and antenatal care (ANC) coverage, mobilisation of frontline workers and strong, decentralised governance structures.

Maternal anaemia in Nepal

The prevalence of anaemia in women of reproductive age varies by regions in Nepal. It is highest in the low-lying area in the south of the country known as the Terai (58%) and lowest in Gandaki Pradesh province (28%), which has mountainous and hilly areas. Pregnant women who are not educated are almost twice as likely to be anaemic (40%) compared to those who are educated (22%), and only 49% of women are currently meeting the recommended minimum dietary diversity2.

Distribution of IFA tablets among pregnant and postpartum women was initiated in the 1980s to improve micronutrient status and reduce the prevalence of anaemia; however, by 1997, only 10% of pregnant women were found to be consuming IFA tablets and just 2% of women consumed at least 90 tablets (the recommended quantity)3. Research carried out by the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), Micronutrient Initiative (MI; now Nutrition International (NI)) and UNICEF showed that lack of awareness and limited access to IFA tablets were key barriers to improving coverage and utilisation4.

A national strategy for anaemia control

In 2002 the Government of Nepal launched a national strategy for controlling anaemia among women and children. This included increasing the coverage of and adherence to IFA supplementation among pregnant women; promoting dietary modification, with an emphasis on foods containing bio-available iron; and food fortification initiatives to increase dietary iron intake. The main delivery platforms for IFA supplementation in the strategy were: health facility antenatal and postnatal clinics; outreach clinics (maternal and child health workers and village health workers); and female community health volunteers (FCHVs).

By 2016 there had been a sharp increase in IFA tablet coverage (at least 90 tablets consumed), with 90% of women aged 15-49 years receiving some IFA tablets and a decrease in anaemia among pregnant women2.

Increase in health facilities

Over the last decade the MoHP has focused on upgrading health facilities and ensuring that quality health services are provided to mothers and children at the community level. This has resulted in increased service utilisation. For example, antenatal care (ANC) coverage more than doubled between 2001 (40%) and 2016 (84%)1. The increase in uptake of IFA between 1990-2016 closely correlates with a dramatic change in the proportion of women receiving at least four ANC visits (an increase from 14.3% in 2001 to 69% in 2016)1, suggesting that access to ANC platforms is a driving factor in uptake of IFA.

The role of female community health volunteers (FCHVs)

FCHVs are the building block of Nepal’s public health system, bridging the gap between communities and families, and the formal health system. By mobilising this near 52,000-strong cadre recruited from the communities in which they work, the government was able to bring the supplements closer to the household level. As part of the intensification of the IFA tablet distribution programme, FCHVs received specific training on IFA distribution, as well as on counselling to increase adherence to IFA and the importance of dietary diversity and foods rich in iron. FCHVs also play a key role in promoting utilisation of available maternal and child health services and raise awareness on IFA and other health and nutrition programmes through monthly mothers’ groups and one-to-one counselling during household visits. The distribution of IFA is reinforced by other frontline workers through primary health centres and outreach and ANC clinics.

Government ownership

Nepal has been through numerous programme phases for anaemia control. In 2005-2006 the first five-year plan of action was prepared and gradually scaled up to all 75 districts by 2012, with training and capacity-building support from donor partners such as Micronutrient Initiative (65 districts), UNICEF (seven districts) and others (three districts).

One of the main contributions to the programme’s success is the high ownership by the government. The MoHP has allocated budget for the procurement of IFA as an essential medical supply since 2004/2005, with 130 million tablets being purchased in 2016/2017. This commitment has helped to prevent supply gaps and enabled the delivery of IFA to FCHV level as an integral part of the public health system. After the recent devolution and decentralisation of procurement functions, any shortfall in supplies has also been effectively managed at the local level.

In 2016 the MoHP began weekly IFA supplementation for adolescent girls (10-19 years of age), using existing school health and nutrition platforms. School teachers and students are mobilised to detect pregnant women in the community and to encourage them to visit FCHV’s house to collect IFA tablets. The FCHV network is also being used to reach adolescent girls who are out of school, identifying them through child clubs and peers. The aim is to reach 1.38 million adolescent girls by 2021: nearly 1.2 million in this group have been reached by 20185.

Nutrition-friendly local government initiative

Strong local governance and social accountability at the village development committee level6, through which the FCHVs provide maternal and child care services, are other factors that supported the IFA intensification programme between 2002-2016.

Following Nepal’s decentralisation in 2017, local governments of 308 rural and urban municipalities signed a declaration to eliminate malnutrition within the next five years and develop their local government as ‘nutrition friendly’, with effective implementation of the national multi-sector nutrition reduction plan. Many local governments promote four or more antenatal checkups during pregnancy and adherence to the consumption of at least 180 IFA tablets7 through various incentives, such as provision of eggs and iodised salt packs. With support from the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, there are plans to develop indicators for nutrition-friendly local governments, including coverage of IFA and dietary diversity.

Challenges with adherence and coverage

The percentage of pregnant women who consume at least 180 IFA tablets varies by age and geography. Adherence during pregnancy is lowest among the age group 40-49 (26%) compared to women aged 20-29 years (44%); in the Terai region (37%) compared to the mountains (49%); among women who are not educated (28%) compared to women with secondary education or more (59%); and in rural areas (38%) compared to urban areas (44%)1.

Although there was a significant decline in anaemia between the late 1990s and 2006, anaemia among pregnant women increased to 48% in 2011 and was reported at 46% in 2016. The prevalence of anaemia among breastfeeding women has also increased, from 40% in 2006 to 46% in 2016. Next steps are to better understand the reasons for the gaps in coverage and compliance in different target groups, ecologies and provinces. Further analysis of the NNMSS 2016 is underway to better understand the factors contributing to anaemia among women in Nepal.

Lessons learned and next steps

Although country experiences need to be contextualised, there are a number of factors that contribute to the increased coverage of IFA supplementation in Nepal that could be applied elsewhere. These include: bringing maternal nutrition services closer to the community via community-based health worker networks, underpinned by strong social mobilisation, integration and reinforcement through all possible platforms; including IFA in the essential nutrition supplies of the government and ensuring uninterrupted supplies; reporting using the existing sector management information system; strong monitoring and periodic assessments to review the situation; and strong support and collaboration from development partners.

However, it is likely that a combination of strategies is needed to further reduce anaemia among women in Nepal. The MoHP plans to include other components in its updated national nutrition strategy, such as improving the coverage of and adherence to IFA supplements, particularly in low coverage and compliance areas and target groups; improving iron fortification in line with international standards, as well as improving access to calorie-adequate, diverse and nutrient-rich diets; infection control programmes with continued deworming; and improving household and environment sanitation.

Footnotes

1Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS) (2016).

2Nepal National Micronutrient Survey (NNMSS) (2016).

3NNMSS (1998).

4Malla (2001) Anaemia in Nepal Report. Micronutrient Initiative

5HMIS target, MoHP 2018/2019

6Since 2017 VDCs have transitioned to gaupalikas (rural municipalities) under the new federal local governance structure.

7180 tablets is the recommended dose during pregnancy (from Week 16 until delivery)