Unlocking the power of maternal nutrition to improve nutritional care of women in South Asia

Unlocking the power of maternal nutrition to improve nutritional care of women in South Asia

Zivai Murira is the Nutrition Specialist at UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, based in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Harriet Torlesse is the Regional Nutrition Advisor at UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia, based in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Nutrition has never been as high on the political agenda in South Asia as it is today. All countries have committed to Sustainable Development Goal 2 to end hunger and many have developed and resourced multi-sector nutrition plans to meet the global targets on child stunting, wasting and overweight. However, there is a danger that women will be left behind in the regional momentum to improve nutrition unless greater attention is given to the nutritional care of women.

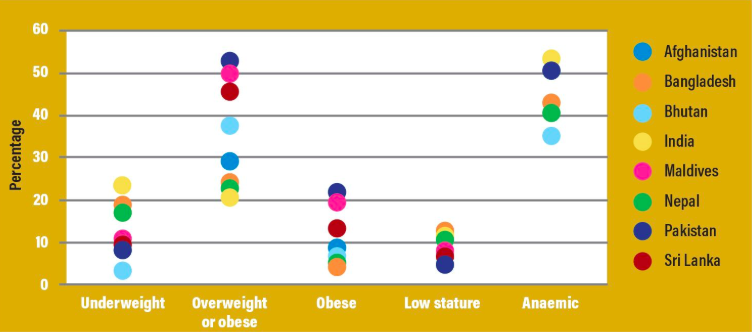

Poor maternal nutrition increases the risk of life-threatening birth complications and diminishes the health and wellbeing of women. The nutritional status of women is improving in South Asia, but progress is uneven and slow. One in five women is underweight (body mass index <18.5 kg/m2); one in 10 are of short stature (height <145 cm); and anaemia is a severe or moderate public health problem in seven out of eight countries1 (see Figure 1). Disparities persist, with undernutrition concentrated in the most marginalised and disadvantaged communities and groups. Meanwhile, the nutrition challenges are becoming even more complex, because the prevalence of overweight is increasing at an alarming rate in women and now exceeds underweight in all countries in the region, except Bangladesh and India.

Figure 1: Nutritional status of women in South Asia

Poor maternal nutrition also has consequences for children. Despite high rates of economic growth, South Asia has a disproportionate number of children under five years old who are stunted (59 million) and wasted (26 million) (Joint Malnutrition Estimates, 2019). The region also has the highest proportion of low birth weight infants in the world (27%)2. This paradoxical phenomenon has been coined the “South Asian Enigma” and is rooted in gender inequalities: there is consistent evidence from South Asian countries that children are more likely to be stunted or wasted if their mothers have a short stature, low body-mass index, are less educated, or gave birth in adolescence1.

Policy and programme solutions to maternal malnutrition require a combination of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive solutions that address immediate, underlying and basic causes. In the context of South Asia, which has the second-lowest regional score on the 2017 Global Gender Gap Index, approaches must address women’s empowerment and place women at the centre of these solutions.

In 2016 the World Health Organization released its Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience for women, which include eight nutrition-specific interventions. A recent review3 found that almost all countries in South Asia have policies on the two interventions that are relevant in all contexts (counselling on healthy eating and physical activity to prevent excessive weight gain, and iron and folic acid supplementation). However, few countries have adopted the six context-specific nutrition interventions and it appears that some may not have fully considered the conditions under which they apply.

In addition to these policy gaps, a range of barriers at maternal, household and health system-level reduce the likelihood that women receive nutrition-specific interventions during pregnancy1,3. Even long-running interventions reach too few women; for example, less than 40% of pregnant women take iron folic acid supplements for at least 90 days in Afghanistan, India and Pakistan. Many of the maternal and household barriers reflect women’s low empowerment, such as low women’s education and knowledge, low self-efficacy, and inadequate support from husbands. Health-system barriers vary from one setting to another, but can be overcome with well-designed, community-based programmes that are based on formative research, reach pregnant women in their homes and communities, engage influential family members, and strengthen the capacities, supervision and motivation of community health workers.

While the health system plays a crucial role in improving women’s nutrition, it cannot act alone. Coordinated actions by food, health and social protection systems are needed in South Asia to improve the dietary intake of women by increasing the supply, affordability and desirability of nutritious foods, and enhancing the knowledge and skills of women to prepare them. The health and education systems should work together to reach school-age and adolescent girls with interventions to improve their nutrition literacy and nutrition status. In addition, a positive legal and policy environment to end child marriage, combined with initiatives to keep adolescent girls in school and promote positive societal attitudes towards girls, can help to empower adolescent girls and protect them from early marriage and adolescent pregnancy.

Efforts to improve maternal nutrition have been greatly constrained by the lack of data and information to bring visibility to the issue, build accountability and guide decisions. Most – but not all – health information management systems in the region include an indicator on the coverage of iron and folic acid supplementation, but countries are not tracking other essential interventions, such as nutrition counselling and calcium supplementation. In addition, greater investment in studies, research and evaluation is needed to illuminate the context-specific pathways to improving maternal nutrition.

Many of these issues were raised at the regional conference organised by the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia on Stop Stunting/The Power of Maternal Nutrition in 20184. This conference brought together government representatives from all eight SAARC member countries, development partners and researchers to discuss the nutritional care of women during pregnancy and postpartum. The conference culminated in a set of 10 key actions to guide country and regional plans to improve maternal nutrition (see Box 1). One of these actions is to find opportunities to exchange knowledge and experience between countries on efforts to improve maternal nutrition; this need catalysed the development of this special, themed issue of Nutrition Exchange.

Women, children, families, communities and nations will all benefit if South Asia’s women are well-nourished. As stakeholders concerned about the wellbeing of women and prosperity of the region, we must do more to bring maternal nutrition to the forefront of national approaches to disrupt the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition and reach global nutrition targets. With tremendous political momentum on nutrition in the region, we need to grasp this opportunity now and build the evidence and confidence that change is possible. The articles in this issue share the experiences of countries in the region to improve the lives of women and their children through a range of nutrition interventions.

Footnotes

1Torlesse, H. & Aguayo, V. (2018). Aiming higher for maternal and child nutrition in South Asia. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14(Suppl 4), e12739. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30499249

2UNICEF-WHO (2019) Low Birthweight Estimates. Levels and trends 2000-2015 www.unicef.org/media/53711/file/UNICEFWHO%20Low%20birthweight%20estimates%202019%20.pdf

3UNICEF (2019). Policy Environment and Programme Action on the Nutritional Care of Pregnant Women During Antenatal Care in South Asia. UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia: Kathmandu.

4UNICEF & SAARC (2018). Stop Stunting | Power of Maternal Nutrition. Scaling up the Nutritional Care of Women During Pregnancy. Conference Report. UNICEF Regional Office for South Asia: Kathmandu.www.unicef.org/rosa/reports/stop-stunting