Nutrition, resilience and the genesis of AGIR

By Jan Eijkenaar

By Jan Eijkenaar

Jan Eijkenaar has been ECHO’s Technical Assistant in support of a resilience approach and the roll out of the AGIR Alliance from September 2012 to April 2015, based in Dakar. This followed a six-year assignment for the establishment and coordination of ECHO’s Sahel Plan in response to food and nutritional insecurity in the West Africa Sahel region. An engineer by training, he has worked in humanitarian emergency aid from the late 1980’s and as an independent evaluator, mainly on the African continent. His expertise and interest covers project and programme design and M&E, strategy and policy work on early response planning, nutrition security and resilience as well as promoting synergies between humanitarian aid, development work and governance.

Jan Eijkenaar has been ECHO’s Technical Assistant in support of a resilience approach and the roll out of the AGIR Alliance from September 2012 to April 2015, based in Dakar. This followed a six-year assignment for the establishment and coordination of ECHO’s Sahel Plan in response to food and nutritional insecurity in the West Africa Sahel region. An engineer by training, he has worked in humanitarian emergency aid from the late 1980’s and as an independent evaluator, mainly on the African continent. His expertise and interest covers project and programme design and M&E, strategy and policy work on early response planning, nutrition security and resilience as well as promoting synergies between humanitarian aid, development work and governance.

Sincere thanks and gratitude to all the great persons and professionals who continue to contribute so much to nutrition care, innovation and equitable access to adequate basic services - fundamental to the notion of resilience and the success of AGIR - in the communities and generously across the sectors at all levels in the West Africa Sahel region. The insight and support of so many ECHO colleagues, partners and counterparts have been invaluable. This article reflects the professional experience and opinion of the author and not necessarily that of the European Commission.

The 2012 Sahel crisis and AGIR’s early beginnings

The Global Alliance for Resilience Initiative (AGIR) is still in its relative infancy; launched in Ouagadougou in 2012, it is expected to run over 20 years until 2032. Yet it has already achieved much. It marks the first common understanding of the persistent and profound causes of vulnerability in the Sahel and West Africa region. It is a political recognition by the region and the world that fundamental and long lasting measures must be put in place to benefit this highly at risk population affected by food and nutrition insecurity. AGIR is framed in terms of ‘resilience building’ and sets an ambitious political target of ‘zero hunger’.

In a region facing enormous challenges, including the probable doubling of the West Africa Sahel population over the next 20 to 25 years from the current 370 million, and staggering malnutrition prevalence that may permanently affect up to half of the future generation, AGIR is an essential undertaking. Every year in the Sahel, since at least 2012, some 20 million people face serious to extreme food and nutrition insecurity and around 1.5 million children1 under the age of five years are expected to be admitted to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) treatment programmes.

Heightened interest in the concept of ‘resilience’ for the Sahel region of West Africa really began following a field mission to Niger and Chad that ECHO2 organised for the EU Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid, Kristalina Georgieva, in January 2012. The severe food and nutrition crisis in the Horn of Africa throughout 2011 was beginning to abate. African leaders at the September 2011 Nairobi Summit were calling for a fundamental change in the approach to responding to these severe recurring crises. Key international actors, including the European Union (EU), USAID, the World Bank and the United Nations (UN), had started to build a high-level initiative. Eventually named SHARE – Supporting Horn of Africa Resilience – it aimed to “close the gap” between relief and development, enhance resilience and promote long-term solutions.

By late 2011, the food and nutrition security outlook for the Sahel and West Africa region looked bleak. Even though there was some disagreement about the likely scale and severity of a 2012 food and nutrition crisis in the Sahel, a joint mobilisation plan by ECHO and DG DEVCO3 at the end of 2011 allowed for the early mobilisation of planning, preparations, pipelines and resources of implementing partners and other donors. It led to an unprecedented Sahel regional emergency response of 1.13 billion USD by the end of 2012.

With both the shadow of the 2011 crisis and the Nairobi call for building resilience - rather than investing in costly repeated relief - still fresh in her mind, the EU Commissioner focussed on an early large crisis response and on generating political interest in a resilience building approach for the West African Sahel region. By that time, ECHO had entered into its 6th annual regional Sahel Plan to combat malnutrition aimed at saving lives at scale and lobbying for a durable reduction and prevention of malnutrition.

ECHO’s approach, activities, partner-network and expertise that it had built up and established since the Niger nutrition emergency of 2005 provided a platform and opportunity to explore the resilience concept for the Sahel region. Meanwhile DEVCO, who were already involved in a resilience approach in the Horn, extended its interest in applying a ‘resilience lens’ to the West Africa Sahel region. Meanwhile, the first signs of preparation for the 11th European Development Funds4 (EDF) were on the horizon. The timing was therefore right for ECHO’s continued efforts to lobby for a Linking Relief to Rehabilitation and Development (LRRD) approach so that prevention and treatment of malnutrition at scale would be funded by development cooperation and national government budgets. This is similar to the ‘resilience’ approach with its inherent goal of eventual phase-out and exit from fluctuating humanitarian funding that had done little to address structural chronic crisis needs.

In effect, the energy and interest behind the regional food and nutrition Sahel response converged, resulting in preparations for the set-up of a resilience initiative in West Africa. However, the particularly strong regional links, interdependencies and economic integration in West Africa compared to East Africa were very clear from the outset. The presence and role of three West African regional organisations (ROs) - CILSS (Permanent Interstate Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel), ECOWAS (Economic Community Of West African States) and WAEMU (West African Economic and Monetary Union) - was a significant factor in facilitating a resilience approach in the region.

With the 2012 crisis in full swing, the hunger-gap approaching and public and political interest high, swift guidance was needed to establish a feasible, robust, politically supported AGIR in the region. The aspiration was also to avoid another short-lived, external, donor-driven and ultimately unsustainable ‘big plan’. The Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC/OECD), part of the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) in Paris and created in 1976 as an international solidarity group for the West Africa Sahel, was willing and able to broker political acceptance and commitment by the region in a short time. The three RO’s therefore agreed to take the lead as the concept gradually took shape in the form of an Alliance - the ‘Alliance Globale pour l'Initiative Résilience’ - AGIR. At that point, important questions remained about the nature of AGIR and how to set it up.

The making of AGIR

AGIR was formally presented at a high level meeting organised by the EU Commissioner in Brussels on 18 June 2012. At that event, an agreement was reached to launch a multi-stakeholder platform led by CILSS, ECOWAS and WAEMU for the West Africa Sahel region called AGIR. The principle aim of AGIR was to push resilience higher up the political agenda and to “encourage greater donor support for sustainable action to strengthen the resilience of the most vulnerable populations”. A series of meetings and outputs were to be achieved before the end of that year, in particular the formulation of a Regional Road Map for AGIR.

The first AGIR meeting of the three RO’s took place in Abidjan on 10 September 2012. The meeting resulted in an official joint position paper on how to approach resilience as part of the regional process of formulating the direction and content of AGIR. The initial vision was to prioritise agricultural production and the development of regional and national agricultural policies. This single-sector focus was a logical continuation of regional food-security priorities that preceded AGIR emanating from the Regional and National Agriculture Investment Plans that are rooted in NEPAD’s5 Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP, 2003) and the regions own subsequent agricultural policy ECOWAP (2005).

Although not really changing the RO’s own strong preference for a dominant agriculture focused orientation of AGIR, the series of extensive consultations with all actors – including civil society organisations, the private sector and international non-governmental organisations (INGO’s) - that followed in October and November that year proved that the process and group of stakeholders as a whole was strong enough to resist the imposition of a single viewpoint.

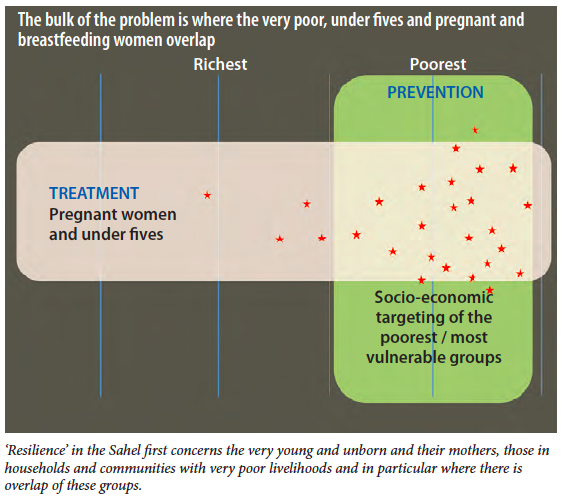

The first really decisive meeting involved AGIR’s Senior Expert Group (SEG) that took place on 7 and 8 November 2012 in Paris at SWAC/OECD. The EU’s delegation, which is the lead donor for the international community in support of AGIR, emphasised the need for a political vision and approach to address the structural drivers of food and nutrition crises focussing on very poor households. With considerable support from other donors (USAID), the UN (notably UNICEF), civil society organisations and INGO’s, the meeting managed to get social transfers, livelihood support and social protection (Pillar 1) as well as nutrition and healthcare (Pillar 2) adopted as two of the four strategic objectives of AGIR for building resilience. Equally important was consensus about the priority target groups of AGIR. These were identified as groups who lacked the most basic resources for the protection of their lives and livelihoods and those most at risk of impaired personal development and capacity to be resilient to future threats of malnutrition and associated morbidity. AGIR’s targeting of the latter category, all children under the age of 5 years and in particular the under 2’s and all pregnant and breastfeeding women, was recognition of the view that a person’s health and capacity to learn, develop and be resilient starts from conception. It also reinforced a formal link with the 1,000-Day Initiative and Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement.

Resilience priorities and benchmarks

A first draft Regional Road Map was quickly written-up by SWAC/OECD and circulated in order to inform the core principles of the political Joint Statement of AGIR. At this point there was little time left before the official launch of the AGIR scheduled to take place in Ouagadougou at the 28th RPCA (Food Crisis Prevention Network) meeting in early December. This high level meeting was to be attended by representatives from the West Africa region, several African and Western countries, the EU, the USA, the UN and other international and regional organisations.

The next decisive moment occurred on the evening of the drafting of the final text before the launch of AGIR on 6 December 2012, when a small team including the EU, USAID, France, UNICEF, WFP and UN OCHA, as well as the three RO’s and SWAC/OECD, finalised AGIR’s formal Joint Statement of principles. This political declaration by the region still lacked quantitative targets for measuring AGIR’s success. Pressed for an answer and just having signed a commitment to start working towards achieving ‘Zero Hunger’ in the West Africa region, ECOWAS proposed ‘Zero Hunger in 20 Years’ as the target. Appropriately ambitious and matching the level of urgency in the Sahel, this was adopted as AGIR’s main stated political purpose. This launched the Alliance, which in the words of SWAC/OECD, “is neither an initiative nor a policy. It is a policy tool aimed at channelling efforts of regional and international stakeholders towards a common results framework”.

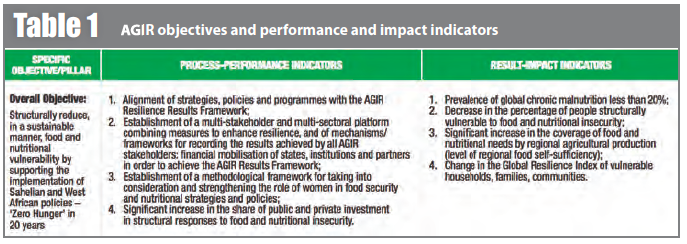

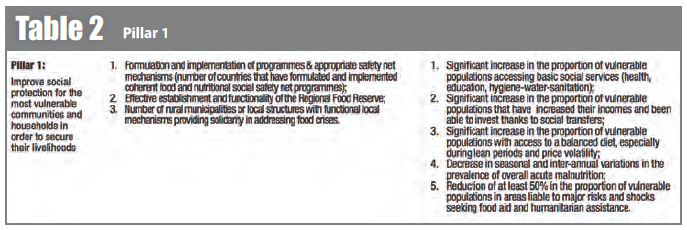

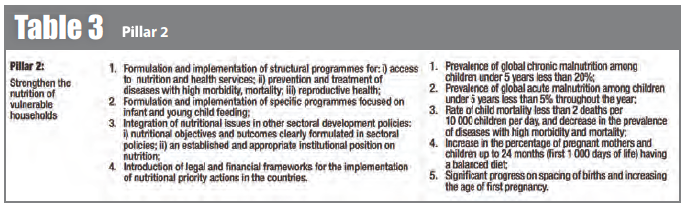

The last vital element to finalise the AGIR Regional Roadmap was identifying and defining indicators for its overall aim and the four underpinning pillars as an example of a measurement framework and as a reference for all subsequent national AGIR roadmaps (now called National Resilience Priorities (NRP-AGIR, or PRP-AGIR in the French acronym).

Held in Lomé in March 2013, just some weeks before the 2013 RPCA in Paris and adoption of the AGIR Regional Roadmap, both ECHO and DEVCO were part of a small drafting team led by the three RO’s and SWAC. With input from the UNICEF expert, vital nutrition indicators and benchmarks were included as main success criteria (Result-Impact Indicators) notably for the Overall Objective and for the 1st and 2nd Pillars, in the document (see Tables 1, 2 and 3).

The 20% chronic malnutrition prevalence ceiling is a critical benchmark (overall and Pillar 2) as is the 5% global acute malnutrition (GAM) rate ceiling throughout the year (Pillar 2). Another key impact indicator is the one describing a significant increase in the proportion of vulnerable populations with a balanced diet, especially during the lean periods and periods of price volatility (see Pillar 1, Table 2).

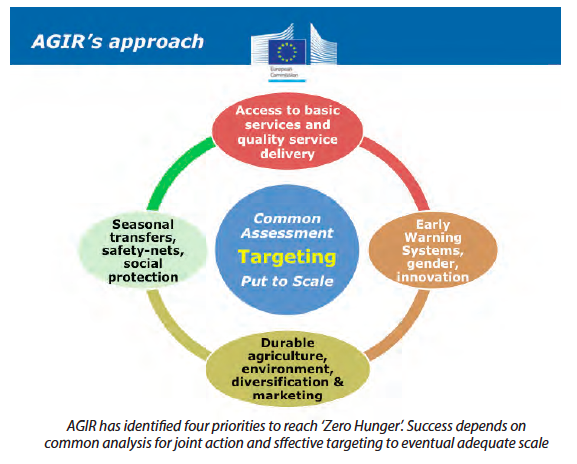

At this point, AGIR had become equipped with a workable toolbox, a balanced set of four strategic objectives and a clear target population. It had ambitious political aims over a realistic timeframe that matched the immense food and nutrition security challenges faced by the region. It also had a reference and measurement framework. All of this had been accomplished in less than 10 months. It represented a major shift from the previous dominant view and priority given to food production and availability, adding vital dimensions of household economy, malnutrition prevention and the priority target groups for building resilience and reducing chronic and acute crisis needs. The AGIR Alliance represents an unprecedented opportunity for the Sahel and West Africa region. The proposed process, principles and parameters to get AGIR implemented and eventually obtain results and achieve impact is a major innovation for the region. It now remains of paramount importance that all 4 AGIR Pillars receive equal and well-coordinated support.

AGIR in practice: the Communes de Convergence approach in Niger

It is still very early to find examples that demonstrate the impact of activities included in the PRP-AGIR process. Niger’s PRP-AGIR, formally adopted in March 2015 as the first National Resilience Priorities document in the region, is integrated into Niger’s national 3N initiative “Nigériens feed Nigeriens" to further strengthen 3N’s resilience dimension. There is a perfect match between the AGIR roadmap and 3N Initiative particularly in terms of the fundamentals: vision, aim and objectives, pillars, targets and modes of implementation approaches. The 3N Initiative is therefore an appropriate framework for the implementation of Niger’s NRP-AGIR ambitions.

With this perspective in mind, the "Communes de Convergence" (‘coming together in local municipalities’) approach was initiated in early 2014 under the 3N Initiative. Designed and launched by 3N’s High Commissioner, with the support of international Technical and Financial Partners (PTF in French) and notably several UN agencies, it is considered a to be a first comprehensive practical application of Niger’s NRP-AGIR. The approach aims to embody 3N’s cardinal principle that the municipality must be the entry-point for action, from identification, planning and implementation to monitoring, completion and evaluation of interventions. The Communes de Convergence approach thus also reinforces the process of decentralisation of governance, given that decisions made closer to where people live are more in tune with their realities and concerns.

Communes de Convergence involves communities, actively and voluntarily from the outset, ensuring that local development priorities contribute to the strengthening of the resilience of vulnerable groups by design and that the Municipal Development Plan (PDC in French) will be aligned to that effect. Priorities include improving agro, forestry, pastoral and fisheries productivity and increasing access to basic social services, nutrition, essential foods, etc.

Thirty-five municipalities have been identified so far for progressive deployment of an initial pilot phase of three years. The goal is to eventually cover all 255 municipalities of Niger. Studies and baseline surveys, as well as a mapping of the presence and capacity of a variety of potential stakeholders everywhere in Niger, were among the criteria for selecting the first batch of municipalities. This joint analysis process involved a series of workshops with the participation of all key stakeholders, including government services at all levels and those involved in implementing projects and programmes in the area.

Out of the 14 key indicators that inform the baseline survey, at least eight directly relate to nutrition and nutrition security. The ambition is to achieve full multi-sector coverage by the collective of actors in the area, as this is considered a prerequisite for the construction of feasible and successful alternatives to recurrent crises, food shortages, cyclical indebtedness of many households, malnutrition and dependencies on short-term aid.

The main working principles include (i) a full effective ownership by the municipality and a budget and capacity available to perform these tasks, (ii) the proper identification of gaps at local governance and technical service levels and the initiative to propose and find solutions, (iii) effective coordination, monitoring and evaluation of actions, of planned investments in the community and their articulation to cover all sectors in synergy, (iv) the inclusion of cross-cutting issues - including gender, population and social cohesion – by all stakeholders, as well as (v) the promotion of a practice of effective multisector implementation by and for all actors.

The Communes de Convergence approach is as much a consultation framework, offering space for dialogue and information and experience exchange in the municipality, as it is a framework for mobilising the necessary funding for the implementation of the selected activities. Backed by strong contributions from the municipal budget, the other part of the funding is sought from PTF’s and implementing organisations and their programmes underway in the area. Chaired by the mayor, the framework includes state and non-state actors, project and programme representatives and the municipal councillors.

With thanks to Mamoudou Hassane, HC3N and AGIR, Niger.

Challenges ahead

At the AGIR Regional Roadmap’s adoption ceremony at SWAC/OECD in Paris early April 2013, DEVCO announced an allocation of at least 1.5 billion Euro of 11th EDF Funds for resilience building by way of a “Food and Nutrition Security and Durable Agriculture” sector focus that will be applied to all West Africa Sahel countries. Even though the modality of EU development cooperation is currently changing towards one of broader ‘state building contracts ‘ rather than more precise sector support, the way that these funds are used for the benefit of the NRP-AGIR will be a measure of the national ownership of AGIR.

This demonstrates how it was hoped AGIR would prove useful, i.e. by ensuring the utilisation of existing funds and programmes in such a way as to orient them to specific objectives and target groups. AGIR is effectively an Alliance that aims to focus the work of actors, policies, programmes and initiatives towards building resilience in order to achieve impact. AGIR therefore is not another fund or initiative, it’s a federating principle.

This ambitious undertaking therefore puts an enormous responsibility for coordination on the shoulders on certain actors, notably AGIR’s international donor support group - the Platform of Technical and Financial Partners (PTFP-AGIR) led by the EU - the ROs and the (16 of the 17 CILSS/ECOWAS countries’) national governments that are engaging in AGIR who are in the process of drafting their own budgeted National Resilience Priorities.

This is where a main challenge for the success of this still young and fragile Alliance is situated; at the level of national coordination. An inclusive process of national dialogue to design, implement, monitor and steer National Resilience Priorities for the benefit of those persons most at risk and affected by food and nutrition insecurity needs to be driven pro-actively and on a permanent structural basis. Widely different sectors and ministries will need to engage, coordinate, design, plan and implement joint approaches on all relevant (community, district, province, national, regional, etc.) levels. This is a huge task.

Aware of these immense challenges, the PTFP-AGIR support group confirmed a sterling commitment to AGIR at the occasion of the RPCA meeting of Abidjan in November 2013, in particular to support the crucial national coordination of AGIR. Unfortunately, progress is slow. Few donors have mobilised dedicated expertise ‘on the ground’ to support national processes to engage successfully with a resilience focus.

Aware of these immense challenges, the PTFP-AGIR support group confirmed a sterling commitment to AGIR at the occasion of the RPCA meeting of Abidjan in November 2013, in particular to support the crucial national coordination of AGIR. Unfortunately, progress is slow. Few donors have mobilised dedicated expertise ‘on the ground’ to support national processes to engage successfully with a resilience focus.

International political interest in resilience and AGIR seems to be waning too. For several important international actors, AGIR may have become just another in a sequence of initiatives without an overarching political significance and ambition. Other policy priorities, such as security, terrorism and migration, are gaining more traction and attention as well. Fortunately, this may not affect AGIR too greatly as it has been politically anchored in the region from the outset.

Also unclear is the extent to which development partners embrace the pro-active culture of a rights-based aid. Such an approach requires a high level of mutual accountability, as declared in Paris in 2005, and a need to address the deep inequalities that underpin a lack of resilience. There is also a question over donors’ internal coherence with regard to their own inter-sector coordination and the thrust of their wider development policies that should at the very least ‘do no harm’ to AGIR’s target groups. One new food and nutrition security programmes supported by several PTFP-AGIR members is raising concerns over the increasing private sector control of food and agricultural systems that may negatively impact on poor rural agriculture communities.

All information on AGIR is regularly updated on its official website hosted and managed by SWAC/OECD at http://www.oecd.org/site/rpca/agir/

More details on the progress of National Resilience Priorities, on-going in almost all countries of the West Africa Sahel region, is posted at http://www.oecd.org/site/rpca/agir/nrp-agir.htm

Footnotes

1This is a planning figure that is regularly compiled by the UNICEF WCARO Dakar Regional Office using data provided by its regional network of national nutritionists, government services and international agencies. The figure is based on a combination of prevalence figures, population estimates, incidence estimates and coverage realities/ assumptions.

2 European Commission's Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection

3European Commission's Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development

4The EDF is the EU's main instrument for providing development aid to African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries and to overseas countries and territories (OCTs).

5New Partnership for Africa's Development, see http://www.nepad.org