Women's nutrition: A summary of evidence, policy and practice including adolescent and maternal life stages

Publication details

Malnutrition - including undernutrition, overweight and obesity, and micronutrient deficiencies - disproportionately affects women and girls, with more than 1 billion women globally experiencing at least one form of malnutrition. While women and girls have a biological vulnerability to certain forms of malnutrition, such as anaemia, a number of economic, social and cultural factors contribute to gender inequalities that limit access to optimal nutrition for women and girls.

Global targets and guidelines

Currently, global targets focus on reducing maternal mortality, reducing the prevalence of anaemia in adolescent girls and women of reproductive age (WRA) (15-49 years), and addressing the nutritional needs of pregnant and lactating women and adolescent girls (PLW/G). With a view to achieving these targets, the following are key international guidelines that include the nutrition of women and adolescent girls:

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2016 antenatal care (ANC) guidelines, covering dietary counselling, balanced energy and protein (BEP) supplementation for undernourished populations, and appropriate micronutrient supplementation.

- WHO 2013 postnatal care (PNC) guidelines, focusing on iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation and nutrition counselling.

- A number of United Nations nutrition guidelines for populations in humanitarian contexts which include women and girls.

However, there are no guidelines that bring together all the nutrition recommendations for adolescent girls and women. In addition, guidelines are not always routinely updated to ensure that they remain relevant and reflect the latest evidence. Guidelines for humanitarian contexts are particularly piecemeal.

Indicators of nutritional status in adolescent girls and women, including short stature, underweight, anaemia prevalence, overweight and obesity, diabetes and raised blood pressure, are routinely included in global and national monitoring and reporting such as the Global Nutrition Report and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs). However, there is currently no routine monitoring of minimum dietary diversity, or other micronutrient deficiencies. Data for adolescent girls are absent, with adolescents 10-19 years often included with ‘other’ demographics, if at all. Guidance on how to assess certain aspects of nutritional status for women and adolescent girls is lacking, with no universal WHO definition of wasting currently available for PLW/G (including no agreed thresholds on mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC)). There is also a dearth of global data on pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and gestational weight gain. This makes it challenging to understand optimal pre-conception nutritional status and healthy weight gain trajectories during pregnancy, as well as how to intervene when necessary.

Nutritional vulnerability of women and adolescent girls

Increased nutrient requirements for menstruation, pregnancy and lactation make WRA and adolescent girls physiologically vulnerable to undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies. While the prevalence of underweight in WRA declined from 14.6% in 1975 to 9.7% in 2014, substantial burdens persist across Africa and Asia, reaching 24% in South Asia. In addition, declines in national prevalence mask ‘hotspot areas’ at the sub-national level in South Asia and parts of Africa. In areas of South and Southeast Asia, maternal short stature (< 150 cm) affects 40-70% of women. The focus in humanitarian and developing contexts has traditionally been on undernutrition but it is now critical to consider overweight and obesity due to their rising prevalence worldwide. The burden of overweight and obesity is particularly high in the Pacific Islands, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East, but very large increases have also occurred in regions such as South Asia, where underweight prevalence also remains high, resulting in a considerable double burden of malnutrition.

Limited data on the global prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies suggest that the highest burden is placed on women and children in lower middle-income countries (LMICs). Approximately one-third of WRA across LMICs are anaemic, 63.2% on average are vitamin D-deficient, 41.4% are zinc-deficient, 22.7% are folate-deficient and 15.9% are vitamin A-deficient. Substantial variations in the prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies are evident between countries. While micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy has documented benefits for micronutrient status and birth outcomes, complete repletion of nutrient status may not be achieved due to chronically deficient diets and increased nutrient requirements in pregnancy. In addition, while the supply and intake of micronutrients has increased globally, this does not necessarily equate to higher intakes in women, particularly in countries where gender inequalities influence intrahousehold food distribution.

Many factors, such as climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, have exacerbated the vulnerability to, and increased the burden of, malnutrition for women and girls, and will continue to do so. For adolescent girls, early marriage and pregnancy have serious adverse consequences for maternal and infant nutrition and health outcomes. Finally, within humanitarian contexts, women are among the most nutritionally at risk. Their existing vulnerabilities may reduce resilience to shocks and can often be further exacerbated by contextual factors that drive or result from humanitarian crises.

Nutrition interventions for women and adolescent girls

Nutrition-related interventions for women and adolescent girls include direct nutrition interventions, such as macronutrient and micronutrient supplementation, and food fortification; and indirect interventions, such as nutrition education and counselling, social protection programmes, sexual and reproductive health services, treatment/management of communicable and non-communicable diseases (NCDs), mental health services, breastfeeding support, nutrition-sensitive agriculture, and women’s empowerment interventions. However, much of the evidence from these interventions focuses on the health benefits for infants and children, with evidence on the nutrition and health outcomes of women often being absent or insufficiently powered to draw conclusions. Multi-sectoral programmes and those that are integrated into national health systems are likely to have the greatest impact and widest coverage. However, the coverage of interventions is largely not well-documented.

Macronutrient and micronutrient interventions

The majority of available evidence on maternal nutrition programmes and interventions focuses on macronutrient and micronutrient supplementation to tackle undernutrition and anaemia in PLW/G. Supplementation is a commonly used intervention to tackle undernutrition in adolescent girls and women, especially during humanitarian situations, with interventions often prioritising PLW/G based on the evidence of a positive impact on infant outcomes. For example, in humanitarian contexts targeted supplementary feeding is recommended by the Global Nutrition Cluster for all PLW/G up to six months postpartum who are moderately wasted. In such emergency contexts, blanket feeding programmes will often include supplementary feeding for all those within higher risk groups, such as PLW/G. In undernourished populations, BEP supplementation is recommended for pregnant women.

However, numerous gaps exist in the guidelines for macronutrient supplementation in undernourished adolescent girls and women, including the following:

- There is no updated WHO guideline on the detection and treatment of adolescent and adult moderate and severe wasting, including in girls and women.

- Guidelines on BEP supplementation for PLW/G are relatively new, and lack detail and implementation guidance. They are also confusing in places as to how they align with existing guidelines for lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS) and other supplementary foods.

- Standardised criteria for the inclusion of PLW/G in blanket feeding programmes are similarly lacking.

Antenatal micronutrient supplementation has established benefits for maternal anaemia and birth outcomes, with some of the latest evidence supporting the replacement of antenatal IFA supplementation with multiple micronutrient supplementation (MMS). However, IFA supplementation continues to be recommended in WHO ANC guidelines, with the exception of humanitarian contexts and ‘rigorous research settings’. IFA supplementation is also recommended for other sub-groups, including non-pregnant girls and women in high-burden contexts and postpartum women; however, limited evidence exists for this in practice across LMICs and implementation guidance on micronutrient supplementation in general is lacking, particularly outside of pregnancy.

Health interventions and integration

The nutrition of adolescent girls and women is integrally linked with the provision of health services, which provide important contact points for nutritional assessment, counselling and referral. However, in LMICs health systems often suffer from a host of issues, including inadequate human and financial resources, lack of availability and suboptimal quality of commodities, inequitable resource allocation and a lack of accountability mechanisms - factors which tend to be exacerbated in humanitarian contexts. While studies have demonstrated a relationship between dimensions of women’s mental health and nutrition, as well as between a lack of women’s empowerment (e.g., through domestic violence) and adverse nutrition outcomes, evidence on the mechanistic links between maternal mental health and nutrition, and on effective screening tools and intervention programmes, is needed. Overall, while ANC services are well-established within health systems, there is limited focus on the integration of postnatal nutrition services and services for non-pregnant women and girls, and a lack of tailored services for pregnant adolescent girls.

Other indirect nutrition interventions

There are insufficient indirect nutrition interventions for women and adolescent girls in LMICs, and there is also a lack of consideration of broader contextual factors (e.g., cultural norms and gender inequalities) within the development of interventions. Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is a fundamental human right, which mutually enforces the right to adequate food. Empowering women is one of the most effective ways to improve nutrition outcomes, both for women themselves and for other members of the household, and can help to break intergenerational cycles of malnutrition. However, recognition of the links between gender empowerment and women’s nutrition is largely lacking in guidelines and programming efforts. In addition, while numerous interventions link climate change to agriculture, they often fail to consider the specific impacts on women, who are likely to be the most affected by climate-related impacts on food security and nutritional status. More evidence is needed to inform the development of multi-sectoral programmes across health, social protection, education and agriculture which prioritise nutrition for women and girls in their own right, and to mainstream core principles such as gender equality and planetary health.

Gaps and Recommendations

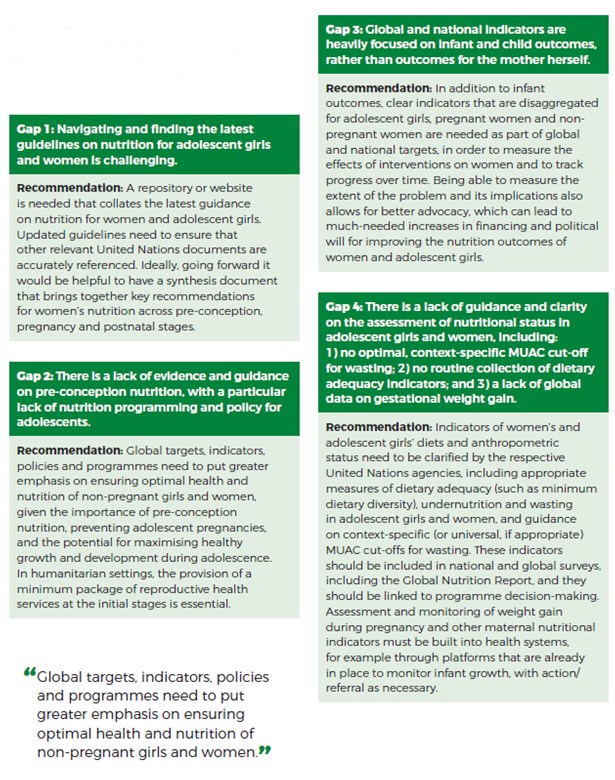

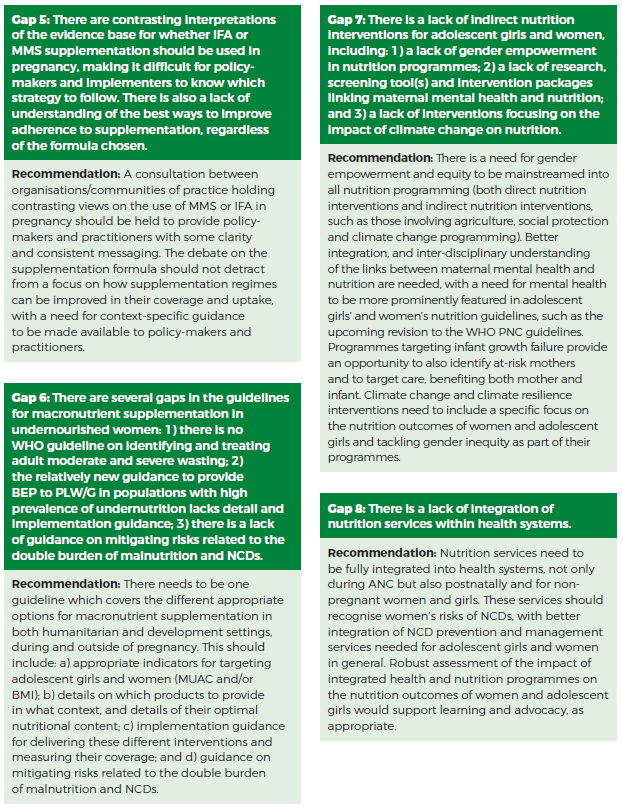

In reviewing the evidence, interventions and guidelines for the nutrition of adolescent girls and women, a number of key gaps and recommendations for progress were identified: