Adolescent Girl Power Groups in Bangladesh: Placing gender equality at the centre of nutrition interventions

By Melani O’Leary, Asrat Dibaba and Julius Sarkar

Melani O’Leary is currently a Nutrition Technical Specialist at World Vision Canada and has over 15 years of experience designing, assessing and implementing health and nutrition programmes in the international development and humanitarian sectors.

Dr Asrat Dibaba is currently the Chief of Party for the ENRICH programme at World Vision Canada. Asrat has over 20 years of work experience covering a range of countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia as a clinician, health and nutrition programme advisor and regional health director.

Julius Arthur Sarkar is currently the Acting Project Manager and Monitoring and Evaluation Manager for the ENRICH programme at World Vision Bangladesh. Julius has over 20 years of work experience in marketing and national and international non-governmental organisations in Bangladesh.

Location: Bangladesh

What this article is about:

Deeply entrenched gender norms in Bangladesh result in discriminatory attitudes and practices that affect the ability of girls to fulfil their right to good nutrition. The article presents the impact of Adolescent Girl Power Groups (AGPGs) promoted by a multi-year maternal and child health and nutrition project in Thakurgaon district, Bangladesh. The AGPG intervention resulted in improved nutrition practices and in shifting gender power dynamics at household and community levels.

Key messages:

- An empowerment approach that puts gender equality at the centre of multi-sector responses to nutrition is critical to breaking intergenerational cycles of malnutrition in Bangladesh.

- Girls need to exercise agency over strategic life decisions, have access to and control over resources and experience informal and formal structures around them as enabling their opportunity to improve their rights to good nutrition.

- The AGPG model is an effective approach to empower adolescent girls to claim their nutrition-related rights and act as agents of change in their families and communities.

ENRICH was a programme supported by the government of Canada through the Partnerships for Strengthening Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PS-MNCH) Initiative. The authors would like to thank the study participants and ENRICH staff in Bangladesh who participated in the data collection.

Background

Adolescent girls in Bangladesh face numerous threats to both their nutritional wellbeing and their human rights including gender-based violence (GBV), gender-based food taboos and child, early and forced marriage (CEFM). Bangladesh has the third highest rate of child marriage globally with 59% of young women married before 18 years of age (UNICEF, 2020). CEFM is a driver of early childbearing with pregnancy at an early age and close birth spacing both contributing to high rates of malnutrition among adolescent girls, with national estimates from 2014 reporting stunting at 26% and underweight at 11% (GAIN, 2018). Adolescent girls also experience high levels of micronutrient deficiencies which are particularly critical for pregnant adolescents as the risk of maternal mortality is doubled for pregnant women with anaemia (Daru et al, 2018). Pregnant adolescents are also more likely to give birth to premature and low birth weight babies. These infants are more likely to suffer from subsequent stunting during childhood and give birth to small infants themselves, creating an intergenerational cycle of undernutrition. Ending the practice of early marriage and ensuring optimal adolescent nutrition is fundamental to improving the nutrition of girls and future generations.

In Bangladesh, gender norms tend to result in discriminatory attitudes and practices that affect girls’ ability to fulfil their right to good nutrition. Cultural bias towards sons negatively impacts resources invested in girls’ nutrition and contributes to parents’ perception of daughters as an economic burden and their marriageability as an ‘asset’. Less than half of Bangladeshi females 10-49 years of age have access to an adequately diverse diet and adolescent girls (aged 10-16 years) are at least twice as likely as boys to go to sleep hungry, skip meals and take smaller meals (GAIN, 2018). Gender inequality is thus both a cause and a consequence of malnutrition among adolescent girls in Bangladesh.

A gender-based analysis, conducted in March 2018 by World Vision (not publicly available), revealed that adolescent girls continue to be restricted by longstanding social norms. It was found that within this patriarchal community men typically make decisions regarding food consumption, education, CEFM and health issues and primarily control and manage the resources that influence nutrition-related decisions for both their daughters and wives. In addition, women and girls have poor access to information about nutrition and have few avenues to shape nutrition services or policies. Within this context, World Vision identified that placing gender equality at the centre of nutrition interventions was essential. Girls who have control over their diet are less likely to suffer from anaemia, miss fewer days of school, have better school performance and have more energy (Nutrition International, 2019). Giving girls agency over their diet and sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) helps girls to avoid unintended pregnancies, attain higher levels of education and has a significant impact on their overall wellbeing throughout their lifetime and for subsequent generations.

Programme description

In 2016, World Vision launched the ‘Enhancing Nutrition Services to Improve Maternal and Child Health in Africa and Asia (ENRICH)’ project in Thakurgaon District, Bangladesh. The five-year project, implemented in partnership with Nutrition International and Harvest Plus and funded by Global Affairs Canada, aimed to reduce maternal and under-five child mortality through nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions to reduce malnutrition in the first 1,000 days of life. The project added a focus on adolescent SRHR and nutrition in 2017.

ENRICH sought to address the discriminatory gender norms that impacted the ability of girls to fulfil their right to good nutrition by overcoming systemic barriers and empowering girls to make their own strategic life decisions (Batliwala & Pittman, 2010; O’Leary et al, 2020). The foundation for the intervention was to understand that girls needed support to define and act on their own goals, alongside ensuring that they had access to and control over the necessary resources and had an environment around them that championed their rights to good nutrition.

ENRICH established Adolescent Girl Power Groups (AGPGs) in five sub-districts of Thakurgaon district of Rangpur to equip adolescent girls with the knowledge, skills and confidence to serve as change agents and promoters of gender equality. Overall, 16 AGPGs were established, reaching a total of 320 girls. Initially, the project conducted community meetings in villages with parents and adolescent girls to gain buy-in and select group members. AGPG participants had to meet the following criteria: school-going adolescent girl, aged 10-19 years, unmarried, living within one of the designated communities and willingness to participate. All ENRICH project staff were trained on the AGPG approach and key discussion topics. From these, 16 female ENRICH project officers were selected as AGPG community facilitators to mentor the groups and support meetings. The training covered basic nutrition topics, SRHR, a male engagement model – MenCare (World Vision, 2013) – and women’s and girl’s rights.

The AGPG activities used a co-design process, allowing members to define the group priorities and agendas for each meeting. Each AGPG democratically elected their leader and met monthly in members’ homes with bimonthly progress meetings held to follow up and plan future meetings. Facilitators assisted with AGPG goal setting and achievement, including developing and reviewing personalised, individual action plans. The AGPG participants received multiple training sessions (over approximately 10 days) on topics such as gender equality, life skills, SRHR and adolescent nutrition. Following the training, the AGPGs were provided with pictorial flip charts and guides for group discussions.

To promote girls’ access to and control over resources, AGPG members were supported with financial literacy and mobilised within the groups to practice individual and collective savings. These collective savings were used for group activities and occasionally to help members within the group. Although most of the AGPG members received a one-off vegetable seed donation, the decision to turn these into income-generating activities (IGAs) (by investing in additional tools from their savings) was entirely led by the adolescents themselves. ENRICH also established community-based nutrition gardens and the girls received health services from their local community clinics including a regular supply of iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets.

ENRICH also worked with parents to champion girls’ rights by, among other activities, promoting intergenerational dialogues. Girls were guided through sessions on how to advocate for their needs and how to make informed life decisions. Alongside this, ENRICH implemented the MenCare Model where men were trained on gender equality and essential nutrition actions and were encouraged to change their perceptions about traditional gender norms. Community facilitators also acted as a liaison between the girls and their parents, discussing issues such as birth registration, GBV and female access to education.

The AGPG intervention was also complemented by other supportive activities to tackle gender-based sociocultural norms such as engagement with religious leaders. AGPGs spread awareness of nutrition and gender equality issues through community and school-based outreach activities such as community theatre.

Finally, the project targeted formal institutions and regulatory frameworks that created barriers for adolescent girls. This included campaigns organised by AGPG members to advocate for gender-responsive and adolescent-friendly SRHR services. Some AGPGs were also supported to establish relationships and communication with relevant government agencies (for example, health units, women’s affairs, police administration) as well as strategically selected civil society organisations. For example, the AGPG members advocated for and coordinated with health units to organise health camps providing free treatment to the community. Similarly, the project coordinated stakeholders to campaign against GBV and CEFM and push local government to act.

From 24th March to 31st May 2020, the government imposed a lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions were placed on gatherings. Most in-person AGPG meetings and activities were put on hold, shifting to virtual engagements, with in-person activities allowed to restart in July 2020, following social distance protocols.

In September 2020, a cross-sectional survey was conducted among all 320 AGPG members (aged 11-22 years) to assess the contribution of the AGPG model on the adolescent girls’ agency and power. Additional qualitative methods included focus group discussions and key informant interviews with AGPG members, leaders and parents. A second quantitative survey was conducted in July 2021 using a web-based data collection tool. The sample included 160 randomly sampled adolescent girls.

Results/outcomes

The AGPG initiative reached 320 adolescent girls directly and 31,294 girls indirectly. The groups were formed in mid-April 2018 and the same groups continued to operate until the completion of the project in June 2021. Over the three-year implementation, there was only one adolescent who dropped out when she got married at the age of 19. In general, older members of the group did not leave but instead took on leadership roles within the groups.

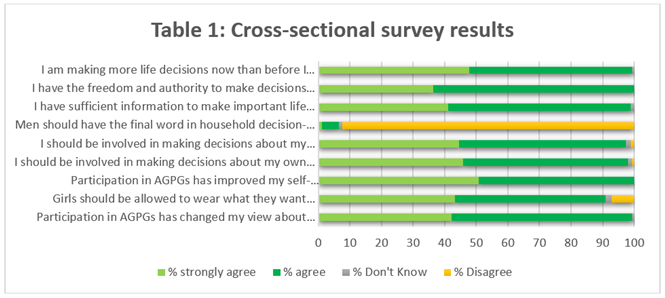

The results of the surveys indicated that AGPGs increased the power, agency and status of participating girls within their families and communities. The cross-sectional survey results (Table 1) concluded that participation in the AGPGs had changed adolescent girls’ views about gender equality with most girls rejecting gender-based stereotypes and expectations. A strong rejection of male-dominated decision-making was expressed and girls reported making more positive life decisions now than before they had joined the AGPGs.

The AGPGs have contributed to this change by empowering adolescent girls through increased knowledge and confidence and by influencing health-seeking behaviour. Frequently cited changes were improved hygiene practices and more regular consumption of foods with higher nutritional value. Moreover, many AGPG members now report that they attend health facilities to collect IFA tablets and seek advice.

The results also suggest that the AGPGs were instrumental in shifting some gender dynamics inside households. Girls and parents spoke about how daughters were comfortable advocating for themselves and parents had become more responsive to their daughters’ opinions, with most being opposed to harmful practices such as CEFM, dowry and GBV. Parents said they noticed an increase in their daughters’ ability to add their voices to family discussions since joining the AGPG. The majority of girls agreed that sharing these opinions translated into real change as their opinions were taken seriously by their parents. Parents confirmed that daughters were influencing household decisions such as the consumption of rice biofortified with zinc. As a father of an AGPG participant expressed, “Previously, I thought that parents have sole authority to decide about the children. But now I’ve started to give importance to my daughter’s opinion. I do listen to her.”

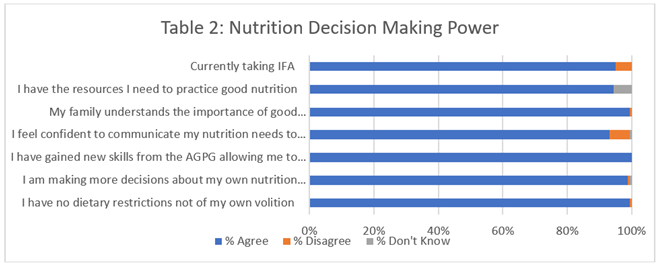

During the second survey, participants also reported more control over decisions related to diet with 87% of girls stating that they make their own decisions about what, when or how much they ate. The majority of girls (84%) said they experienced a change in this norm since joining the AGPGs. Although in 81% of households the father eats first, 58% of girls stated that they experienced a change in this practice since joining the AGPGs with more families eating meals together at the same time and fathers ensuring that food was available for everyone in the household. Furthermore, 99% of girls stated that they currently did not have any dietary restrictions that were not of their own volition, with 81% explaining that this was a change since joining the AGPG. Significant progress was made in decision-making power related to nutrition practices (Table 2).

The AGPGs also contributed to economic empowerment, granting girls more control over financial resources and supporting IGA within the groups. Furthermore, as the girls participated in the IGA during their leisure time, no negative impacts on schooling were observed. Anecdotally, there was a positive impact on schooling and more broadly. As one girl noted during the focus group discussions, “In the past, girls had no choice to buy anything without family permission. Now they can do it by their own decision.” In the quantitative survey conducted in 2021, the AGPG members specifically reported more decision-making power over financial resources with 94% of girls reporting that they could make their own decisions about what to do with the money they received. Significant shifts were also noted concerning parent’s attitudes towards girls’ education and their status within the family. Increased freedom of movement was also referenced as an example of shifting attitudes resulting in expanding opportunities for girls.

Survey respondents referred to the AGPGs as a source of collective power that has catalysed positive changes in their communities. As a group, the AGPG members identified strategies to challenge discriminatory gender norms and promote gender-responsive health, nutrition and hygiene practices. The community has come to view the AGPGs as a source of trusted information that can help to solve some community-level problems. The facilitators spoke of the collective impact of the AGPG, “One person’s voice can be refused, but if 20 girls raise the same voice, it will be accepted.” AGPG community facilitators also attribute some of the progress that the groups have achieved to the existing rapport between World Vision and the families already involved with the ENRICH project. The AGPG’s connection to World Vision and the ENRICH project adds credibility to the information shared with their parents, contributing to AGPG status within the community.

Successes, challenges and lessons learned

The project experienced many successes, a few challenges and some important lessons learned. One key success was the active participation and leadership of adolescent girls within the AGPGs. The co-design approach provided girls with opportunities to define group priorities and to interpret success on their terms. An additional success factor was the girls’ pre-existing feelings about the need for greater gender equality in their families and communities. For many, this desire to learn more and engage with their community for the sake of creating change was what prompted them to join the group. Future programming should expand on this by creating new opportunities for girl-led initiatives.

Another success was the MenCare model which proved to be a successful approach for engaging community decision-makers, pointing to the need for both approaches (AGPGs and MenCare) to be implemented in the same geographic area. ENRICH also engaged other traditional power-holders, such as faith leaders, through targeted workshops. Although the workshops were effective, more transformative change might have been possible using the Channels of Hope model (World Vision, 2021) and by expanding the target audience to include other decision-makers such as elders and community leaders.

Parental engagement was another success as it helped girls to exercise much of what they were learning in the AGPGs. Parents seemed to perceive this increase in girls’ status and position in the community as a boost to their own family status, sharing their sense of pride over community benefits resulting from their daughters’ knowledge and instruction.

The income-generating activities for adolescent girls were another success, enabling girls to translate knowledge into action. Parents also cited this intervention as important for building economic resilience within their families during the pandemic. The girls’ involvement in IGAs allowed them to generate savings that helped their families to procure basic household items while they had less income. The families also consumed vegetables and eggs from AGPG activities during this time of financial strain. Since IGAs were not intentionally planned in the project activities, future AGPGs should include and expand upon them.

One of the lessons learned from the project was that future activities should consider building on the MenCare approach. While the implementation of the MenCare approach was successful in changing male perceptions about the value of girls in the family, future programming should incorporate specific dialogue tools or guides for fathers to encourage intra-household dialogues. Most fathers said that despite improved communication with their daughters, they still found it challenging to discuss reproductive health topics including menstrual hygiene and family planning. The project also missed an opportunity to deliberately engage mothers who have a unique and trusted insight into the obstacles faced by females in their communities. Future programming should mobilise and strengthen women’s groups.

Given the entrenched gender norms in Bangladesh, the project encountered some challenges when targeting gender-transformative attitude shifts. Initially, the campaign against CEFM was faced with community resistance. Some community members felt that since this was a longstanding practice for generations, there were no problems with it. MenCare leaders were instrumental in meeting with these community members to support a better understanding of the risks involved in child marriage. The project also faced some resistance from elders in the community who felt that adolescent girls should not play a role in educating elderly people. The community facilitators played a part in resolving this challenge over time.

Although the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic introduced new challenges, participation in the AGPGs brought several benefits to the girls and their families, strengthening their resilience to the pandemic’s impacts. AGPG members were instrumental in disseminating critical COVID-19 information received from the AGPG groups. Although the girls were not meeting in-person, they received emotional and psychosocial support from AGPG facilitators and continued to connect with AGPG friends via mobile devices during isolation.

Finally, adolescent girls were at increased risk of GBV during the pandemic and AGPG facilitators felt that the open conversations within families about resolving conflict helped to lower the rates of GBV in AGPG families. More inclusive communication and decision-making that considered the needs of daughters, discouraged GBV, raised awareness of the negative impacts of early marriage and improved knowledge about cost-effective and nutritious foods are likely to have helped to protect girls during the lockdown.

Conclusion

The results of the project highlight the potential for the AGPG model to empower adolescent girls to claim their nutrition-related rights and act as agents of change in their families and communities. The AGPG model points to the transformative power of an empowerment approach and ultimately demonstrates that progress towards improved nutrition outcomes is possible when girls exercise their agency over strategic life decisions, have access to and control over resources and experience the informal and formal structures around them as enabling their opportunity to improve their right to good nutrition.

The approach has resulted in a strong promise for sustainability. Alongside the knowledge and skills to continue their advocacy efforts, the AGPGs have demonstrated significant motivation to continue working together. The groups have prepared their annual plans through to the end of 2021 and are continuing to follow their implementation even in the absence of support from ENRICH project staff. The financial literacy and saving skills, along with their IGAs, will continue to ensure that the girls can access and control the financial resources that they need to act upon their goals. Finally, as part of the handover and sustainability activities, ENRICH conducted meetings with multiple stakeholders to identify options to sustain interventions beyond the project’s life. To date, significant progress has been made towards embedding the AGPGs within both government structures and community-based mechanisms. Additionally, the project has linked AGPGs with community clinics for the ongoing supply of IFA and access to health services.

For more information, please contact Melani O’Leary at melani_oleary@worldvision.ca

References

Batliwala, S and Pittman, A (2010) Capturing Change in Women’s Realities. Awid.org. https://www.awid.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/capturing_change_in_womens_realities.pdf

Daru, J, Zamora, J, Fernandez-Felix, BM, Vogel, J, Oladapo, O, Morisaki, N et al (2018) Risk of Maternal Mortality in Women with Severe Anaemia During Pregnancy and Post Partum: A Multilevel Analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 6(5), E548-E554.

GAIN (2018) Adolescent Nutrition in Bangladesh. Gainhealth.org. https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/adolescent-nutrition-in-bangladesh-2018.pdf

Nutrition International (2019) Frequently Asked Questions: Weekly Iron Folic Acid Supplementation (WIFAS) for Adolescents. Nutritionintl.org. https://www.nutritionintl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WIFAS_for_Adolescents_FAQs_2019.pdf

O’Leary et al (2020) A Gender-Transformative Framework for Nutrition. World Vision. https://a5ccf6e5-ee39-4de1-a5a4-d7406d103f94.filesusr.com/ugd/c632d7_a7d415dcfd8b483288c8de14fa3d4744.pdf

UNICEF (2020) Percentage of women 20-24 years old who were first married or in union before they were 18 years old. Girlsnotbrides.org. https://atlas.girlsnotbrides.org/map/

World Vision (2013) A MenCare Manual to Engage Fathers to Prevent Child Marriage in India. Worldvision.org. https://www.worldvision.org/wp-content/uploads/MenCare-Manual-India-Prevent-Child-Marriage.pdf

World Vision (2021) Channels of Hope. Wvi.org. https://www.wvi.org/faith-and-development/channels-hope