Link Nutrition Causal Analysis (NCA) for undernutrition: an analysis of recommendations

This article analyses some of the recommendations arising from Link NCA studies around the world and highlights the importance attached to considering community perspectives.

Carine Magen Fabregat is referent for Link NCA and qualitative methodology at ACF-France

The author thanks Margot Annequin for her contribution to the analysis and Lenka Blenarova (ACF-UK), Dieynaba Ndiaye (ACF-France) and Myriam Ait Aissa (ACF-France) for their review.

Background

Action Contre la Faim (ACF) is a humanitarian non-governmental organisation (NGO) that has been involved in the treatment and prevention of undernutrition for over 30 years. To strengthen the analytical basis of its programmes, ACF developed a structured methodology for conducting a causal analysis of undernutrition, in particular wasting, called ‘Link NCA’1. This method is multi-sectoral, local and participatory, combining quantitative and qualitative data analysis and consultation with local experts and/or the communities involved with tackling malnutrition.

Box 1: About Link NCA

Link NCA (Nutrition Causal Analysis) is an established participatory and results-oriented methodology for analysing the multi-causality of undernutrition to inform context-specific nutrition-sensitive programming. The Link NCA methodology was developed to help researchers to discover the causal pathways of undernutrition, considering multiple sources of data including statistical associations with a variety of individual and household indicators that depict the broader environment, changes in patterns of undernutrition over time and seasonally and recommendations for programming based on the consensus of risk factors likely to be the most modifiable by stakeholders.

To answer these questions, Link NCA studies employ a mixed-methods approach, combining both qualitative and quantitative research methods, and draw conclusions and recommendations from a synthesis of the results. The Link NCA is carried out in the following five steps: the preparatory phase, determining the parameters and methodology; the identification of hypothesised risk factors and pathways through a systematic literature review and initial interviews; community-level data collection including qualitative enquiry and possible quantitative nutrition surveys; the synthesis of the results and building a technical consensus through a final stakeholder workshop; and communicating the results and recommendations and planning for a response.

For more information see https://www.linknca.org/

Since the development of Link NCA, the method has been used by more than 40 studies around the world. This article presents the findings from an analysis of the recommendations made by NCA analysts and the communities involved in the studies. Overall, the analysis aimed to strengthen the ownership of Link NCA results by both the humanitarian actors and the affected communities through (1) clarifying the recommended sectors and intervention modalities according to the risk factors identified by Link NCA; and (2) comparing the recommendations produced by the communities and the analysts.

Methods

The final reports of 43 Link NCA studies, published on the ACF website and in the ACF archives, were used for this study. From these reports, three databases were created and analysed:

- A study database: n=43. This describes the context of the study and the content of the report: country, year of publication, language, funder, partnership context, crisis context, rural/urban context, recommendations etc.

- A risk database: n=725. The risk factor database includes, for each study, the malnutrition risk factors selected and prioritised during the final stakeholder workshop.2 The prioritisation of risk factors is based on a triangulation of the quantitative and qualitative results of each Link NCA and the scientific evidence available on a particular risk factor.3 Each line in the database corresponds to a risk factor. The sectors of activity and the prioritisation (major, important, minor) that are chosen at the final workshop were also entered.

- A recommendation database: n=1646. The recommendation database includes the recommendations issued by the analysts for the 43 studies. If the analyst separated the recommendations from the community, these were encoded separately.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

Five Link NCA studies were conducted in Ethiopia and five in Bangladesh followed by four in Kenya and three in Chad. One quarter of the studies (n=10) were published in 2017 with between two and six studies published annually since 2011. One third of the final reports were published in French, two thirds in English and one report was published in Spanish. Just over half of the studies (n=24) were conducted using the full Link NCA methodology incorporating qualitative analysis, a quantitative assessment of the prevalence of undernutrition and an analysis of the risk factors. Of the studies, 20% (n=9) did not include a prevalence study, with most conducting secondary analyses of existing data, and 10% (n=6) used only the qualitative methods. The largest funder of the studies was the European Union (n=11) followed by UNICEF (n=7). Eight out of 10 studies were carried out by ACF, either independently or in collaboration with other organisations. Four out of five studies (n=34) were conducted in territories with high stunting and five were conducted in refugee camps. The majority (88%) of the Link NCA studies presented risk factors for malnutrition with a median of 20 risk factors identified and ranked across the studies. Apart from three studies, all contained operational recommendations, of which 40% were collected by Link NCA analysts.

Risk factor analysis

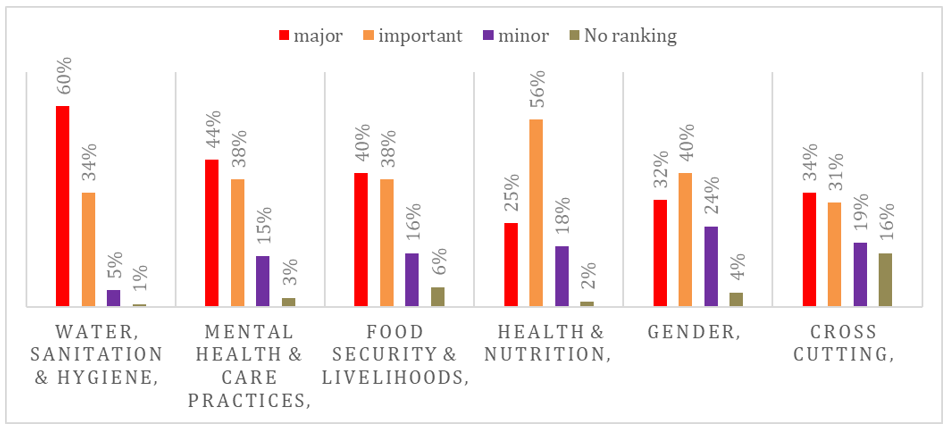

Figure 1 shows the ranking of importance of the identified risks by sector. Risk factors related to food security and livelihoods were identified more often than risk factors from other sectors. Risks related to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) were more frequently ranked as ‘major risks’ across the Link NCA results. These were also more likely to achieve consensus during final stakeholder workshops than other risk factors.

Risks within the health and nutrition sector were ranked as ‘important’ more often than those from other sectors.

Figure 1: Prioritisation of risks by sector

Overall recommendations

Of the 43 published studies, 40 studies made recommendations (from the analyst and/or from the community) where a risk factor was identified/hypothesised and prioritised, giving a total of 1,646 recommendations. Of all the recommendations, 49% came from studies where community recommendations were collected and 21% were community recommendations. These were listed separately by the researchers.

Of all of the recommendations, 29% were related to food security, 22% to health and nutrition, 21% to WASH, 12% to mental health and care practices and 10% to gender. These figures differ slightly from the distribution of risks because multiple recommendations are often issued for the same risk. However, as with the risk factors, recommendations relating to the food security sector were the most numerous followed equally by recommendations for the health and nutrition and water and sanitation sectors.

Community recommendations vs. analysts

Of all the Link NCA studies, 40% (n=17) collected community recommendations through a community workshop/meeting at the end of the survey. The studies conducted by ACF within a consortium collected more community recommendations than studies conducted by ACF alone or by another organisation. While the results must be interpreted with caution due to the small size of the study, it appears that community recommendations were more likely to be collected by analysts in stable contexts rather than during acute crises, in rural settings rather than in refugee camps and in studies using a full Link NCA methodology. For those studies where community recommendations were collected, an NGO’s response plan was more likely to already be in place.

When comparing the recommendations made by the communities with those made by the analysts, there were differences in the distribution of recommendations by sector. Overall, the community recommendations related more to food security and livelihoods and gender than the analyst recommendations. Recommendations around health and nutrition, mental health and care practices were represented more in the analysts' recommendations. The community recommendations were more focused on improving access, building or rehabilitating and distributing inputs than the analysts' recommendations with 43% of the community recommendations relating to improving access to essential services. Among the analysts, recommendations for raising awareness were most common (23%). The reasons for these differences in the distribution of recommendations between the community and the analysts are likely to be many and varied. For example, the relative importance given to gender issues by the communities compared to the analysts may reflect possible gender bias among the experts at the final stakeholder workshops and a tendency for analysts to favour more easily operational interventions such as awareness raising than those of gender-related social transformation. Ultimately, the reasons are perhaps less important than the differences which highlight the importance of a community’s involvement in decision making for its own issues.

Strengths and limitations of community recommendations from Link NCA studies

While the Link NCA methodology adopts a participatory approach, more than half of the Link NCA studies did not incorporate the community recommendations and/or did not highlight these in their final reports. For those studies that did collect the community recommendations, these were often included as annexes and lacked visibility in the reports despite the fact that they differed to the recommendations made by the analysts.

Whether related to women's capacity to make decisions about their children's care, their economic independence, workload and access to contraceptive methods or the involvement of men in the response to malnutrition, women’s voices are rarely heard in scientific publications or in Link NCA expert workshops. However, the collection of qualitative data during Link NCA studies provides an opportunity to investigate and vocalise such areas that may be under-represented in nutrition programmes.

This Link NCA review highlights the need to systematically collect and feature community recommendations in Link NCA reports. This would ensure that community knowledge and perspectives are valued and contribute to a global community health approach in which those affected are involved in the co-construction of the response (Bouville, 2001). This is in line with the Inter Agency Standing Committee commitments to Accountability to Affected Populations[4] and would also contribute to a paradigm shift in humanitarian aid (Ryfman, 2011) with benefits at all levels. Such benefits would likely include better adapted and more appropriate programmes that are, in turn, more effective, a more just and ethical aid relationship that avoids the vertical relationship of power. Above all, the amplification of the voices of those who suffer the consequences of poverty would be better achieved. Consulting communities and prioritising their recommendations can also address the challenge of responding to the large number of risk factors identified in the studies.

Compared to other survey methodologies, Link NCA provides a dominant place for qualitative investigation. This presents an opportunity for NGOs to reposition themselves with the affected populations, to intensify dialogues and to gain a deeper understanding of the determinants of, and responses to, malnutrition (Freeman Grais, 2016). Giving a voice to those affected by malnutrition is particularly urgent in the context of escalating community needs amidst limited resources (Aperçu Humanitaire Mondial, 2022), the need to improve coverage and sustainability of programmes (Blanárová, 2016) and the weakening legitimacy of NGOs in the field.

Box 2. Example of the proposed use of the Link NCA methodology to inform the implementation of the MAM’Out project in Burkina Faso

The MAM'Out project aims to evaluate two innovative approaches to prevent wasting in the Tapoa province of Burkina Faso. The first approach is a child-centred, educational and home-based family development strategy to mitigate the contextual factors affecting households vulnerable to undernutrition. The second consists of a seasonal and multi-annual cash transfer (CT) programme, providing a safety net to economically and nutritionally vulnerable households with children less than two years old. In order to fully adapt this intervention to the Sahel households' context, a deeper analysis of the causes of undernutrition using Link NCA will be conducted. This will help to determine the relevance of CTs in this setting as well as identify the appropriate criteria for targeting the CT programme.

Conclusion and next steps

This analysis of recommendations does not cover all the issues raised by the Link NCAs but it does highlight the need for humanitarian actors to work with greater awareness of the perspectives of individuals and communities. This is part of a global movement to recognise people's capacity to act, critique and exercise their will as humanitarian stakeholders and having their own political agency. Box 2 provides an example of how Link NCA is being used to tailor a CT programme targeting undernutrition more appropriately to the needs of the community. The co-construction of aid projects with the communities concerned should move from intention to action. This approach is all the more urgent as it will respond, at least in part, to the obstacles encountered by NGOs in the field: greater needs, fewer resources, poor coverage of and adherence to interventions and their fragile sustainability. For Link NCA studies, documenting the implementation and follow-up of community recommendations is paramount if the sector is to meet these aims.

For more information, please contact Carine Magen Fabregat at cmagenfabregat@actioncontrelafaim.org

References

Aperçu Humanitaire Mondial (2022, OCHA) https://gho.unocha.org/fr

Blanárová L, Rogers E, Magen C and Woodhead S (2016) Taking severe acute malnutrition treatment back to the community: practical experiences from nutrition coverage surveys. Frontiers in Public Health, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00198

Bouville JF (2001) L'importance de la prise en compte du contexte interculturel dans l'acceptation d'un message pour la santé : l'exemple du projet PAAN d'éducation nutritionnelle. Face à face, 3. http://journals.openedition.org/faceaface/580

Brequeville B (2013) Les ong doivent inscrire leurs actions dans une logique de transformation sociale. https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/FR-Bertrand-Brequeville-septembre-2013.pdf

Freeman Grais R (2016) Responding to nutritional crises in Niger: research in action in the region of Maradi. Face à face, 13. http://journals.openedition.org/faceaface/1045

Ryfman P (2011) Malnutrition et action humanitaire. Perspectives historiques et enjeux contemporains. Savoirs et clinique, 13: 60-70. https://doi.org/10.3917/sc.013.0060

2 The term ‘stakeholders’ should be understood here in a broad sense: technical experts, field workers, community leaders, traditional and religious leaders, political leaders, community-based organisations, official institutions and NGO representatives.

3 Chapter 7 of the methodological guide, available at https://linknca.org/methode.htm.