A peer-to-peer model to improve maternal, infant and young child feeding in Rwanda

Annet Birungi is a Social and Behaviour Change Specialist at UNICEF Rwanda.

Samson Desie is Nutrition Manager at UNICEF Rwanda.

The authors would like to thank the broader UNICEF Rwanda team and UNICEF HQ for their support in developing this work.

|

Key messages:

|

Background

In Rwanda, one in three children under five years of age is stunted and only 17% of children 6-23 months are fed a minimum acceptable diet (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda et al, 2021). This is despite the finding that the percentage of caregivers with comprehensive knowledge of optimal maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) increased from 22% to over 90% between 2013 and 2017 (Rwanda Ministry of Health and Rwanda Biomedical Centre, n.d.). Intensive communication and education campaigns have been delivered to caregivers regarding best practices for MIYCN. Yet, these campaigns appear to have little impact on the overall goal of improving diets which is an important factor in reducing stunting rates. This indicates that shifting knowledge and attitudes is insufficient to address child undernutrition and that it requires multi-sector approaches that ensure food availability and accessibility at the household level, while improving nutrition services and care practices such as food selection, preparation, feeding, and hygiene.

UNICEF, in collaboration with the Rwandan Government, conducted a comprehensive ethnographic study between November 2019 and September 2021to understand the household-leve drivers of nutrition outcomes among pregnant and lactating women and young children. The study deployed an anthropological approach using qualitative methods to study people in their cultural setting with the aim of understanding why nutrition outcomes among children under five were sub-optimal despite a good understanding of adequate MIYCN practices in the population. This preliminary study revealed gaps in the knowledge-capability-pratice chain and recommended a move towards focusing on the final section of the chain where knowledge and capability are translated into better dietary choices (Birungi et al, 2022). It is against this backdrop that the peer-to-peer approach has been modelled and implemented in selected areas since June 2021.

The peer-to-peer approach aimed to build resilience amongst caregivers to better adapt to shocks, such as pandemics and disasters, and to ensure optimal child nutrition under such conditions. The approach targeted five socio-economically diverse districts (e.g., predominantly rural or urban, subsistence agriculture, cattle keepers, or day labourers) to ensure the sample was nationally representative, reaching over 1,540 children under five years of age and their caregivers.

Methods

Design of the peer-to-peer approach

Formative research informed the design of the peer-to-peer approach. A desk review of MIYCN social and behaviour change interventions was conducted to identify suitable interventions that could be adjusted or replicated in Rwanda. Subsequently, a tool was developed and tested to identify the caregivers of children without malnutrition who demonstrated successful MIYCN behaviours/practices known as ‘positive deviant households’ or ‘doers’ and caregivers of malnourished or at-risk children (‘non-doers’) through focus group discussions and interviews. Doers who demonstrated best practices and volunteered their involvement were then selected, grouped and trained as peer supporters. The respective enablers and challenges experienced by doers (peer supporters) and non-doers of successful MIYCN behaviours/practices were explored further and used to inform the framework of the peer-to-peer approach.

Selection of peer supporters

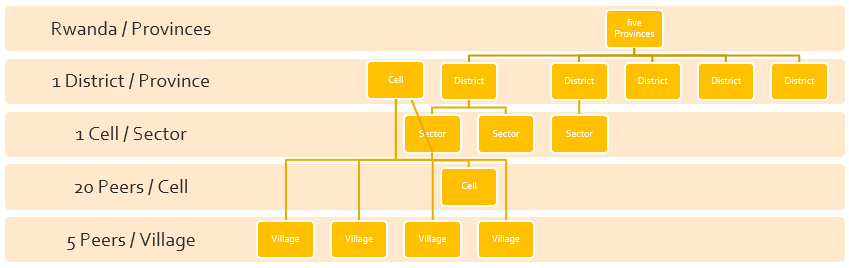

A total of 110 peer supporters were recruited in the pilot phase across the five districts. In each district, one cell was selected per sector, with four villages in each cell then chosen for initial piloting (Figure 1). Each cell had approximately 20 peer supporters, with one acting as coordinator for the village peer supporters. Each village, comprising 10 households, had five peer supporters, one of whom acted as the leader.

Figure 1. Peer-to-peer model structure

Capacity development of peer supporters

The goal of the peer-to-peer model was to create self-help groups of parents equipped to provide practical support to other parents through frequent, accessible, flexible, and supportive interactions. Peer supporters received a series of training on interpersonal communication and mentorship to enable them to transfer knowledge and skills effectively to their fellow parents/caregivers. Peer support focused on food selection, the use of food available in the household, and the preparation of age-appropriate food (e.g., the healthiest ways to cook vegetables, soups, porridge, and purees). Peer support was also given on the timely introduction of complementary foods from six months of age, optimal meal frequency and volume, the optimal nutrient status of pregnant and breastfeeding women, and effective hygiene practices – such as optimal hand washing, faecal disposal, and the treatment of drinking water. Appropriate food safety and storage as well as the involvement of men in childcare were also included. Peer supporters were also trained how to take mid-upper-arm circumference measurements and about the subsequent referral of identified malnourished cases.

Intervention

During implementation, each peer supporter conducted twice-weekly hour-long home visits to five households with at least one child under five years of age. The households were identified in consultation with community health workers regarding nutritional status, and with local leaders and social workers regarding economic status to ensure homogeneity across household economies. Households were then categorised according to the nutritional status of their children.

Face-to-face communication was the preferred channel through which peer supporters interacted with their peers to select food, cook together, and explore age-appropriate ways to feed a child, including breastfeeding, complementary feeding and the use of multiple micronutrient powders (MNPs). Nevertheless, short messages and telephone calls were effective mitigations implemented during periods of COVID-19-related restrictions. Training activities for community health workers on risk communication and community engagement activities were conducted via Zoom, WhatsApp, email, and over the telephone (Birungi et al, 2021). Key messages on MIYCN were disseminated through print and electronic media channels as well as via community radio stations. Peer supporters used their own resources such as airtime for calls, WhatsApp, and SMS bundles to ensure continuity of their tasks as well as the continual exchange of information. Simplified visual education materials on nutrition-related topics were found to be useful even in areas where parents and peers had low literacy rates. Peer supporters also supported their peers to establish home gardens to produce vegetables and fruits, thereby reducing daily food costs to meet nutritional needs.

Monitoring and reporting

Each peer supporter provided monthly reports based on a diary of tasks that they maintained. Reports were then compiled and sent up through each level: village, cell, community health worker, and district health hospital. After the reports were approved at the district level, they were sent to the National Early Childhood Agency – the relevant government body – for analysis. The reports contained quantitative information on the support provided, changes in MIYCN practices and behaviours, and malnutrition cases and referrals, as well as an exploration of observed challenges, lessons learned, innovations, and opportunities. To ensure sustainability, the production and dissemination costs of the reporting formats were covered by the district budget.

A key sustainability mechanism was the consistent engagement of government leadership and the training of relevant staff at both central and grassroots levels throughout the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation stages. Key staff at district and community level were trained on data collection, routine monitoring, and supportive supervision to enable the scale-up of the model following the piloting phase. Peer supporters worked under the supervision of trained local authority staff in collaboration with the National Child Development Agency staff, including progress monitoring of the frequency of home visits, group discussions, and the time each peer supporter spent with a peer. In addition, peer supporters met monthly at cell level to share experiences, challenges, and solutions.

Evaluation

To determine the effectiveness of the peer-to-peer intervention, baseline (May 2021) and endline (July 2022) household surveys were conducted in the intervention and control areas on key MIYCN indicators (minimum acceptable diet, meal frequency, minimum diet diversity, consumption of MNPs, and hand hygiene for caregivers of children under five years). District-level anthropometric data was also collated and focus group discussions were conducted in collaboration with health centre management teams. At endline, a total of 560 households with pregnant and lactating woman and/or children 6-23 months were selected for the quantitative survey through the random sampling of 20 selected intervention villages and 20 matched control villages. A total of 25 focus group discussions were held across the intervention and control villages, among groups of six to eight mothers, fathers and community health workers.

Results

Although the control and intervention groups were not homogenous for certain indicators at baseline, a general trend of intervention efficacy can be seen across the results (Table 1). Both minimum dietary diversity and minimum meal frequency improved significantly for children aged 6-23 months in the intervention group compared to the control group.

Misconceptions from mothers about MNP usage, mainly regarding the perceived side effects, are among the factors currently limiting their use (Dusingizimana et al, 2021). The intervention contributed to an increased uptake of MNPs whereby the use of MNPs increased by 14.8% (P<0.001) in the intervention group compared to a slight decrease in use among the control group. However, both the intervention and control groups optimised their preparation of food with MNPs with almost all participants mixing the powders with cooked or semi-solid foods by the end of the study period.

Table 1: Assorted complementary feeding indicators for children aged 6-23 months

|

Indicator |

Control |

Intervention |

||||

|

Baseline (%) |

Endline (%) |

P-value |

Baseline (%) |

Endline (%) |

P-value |

|

|

Minimum dietary diversity 6-23 months* |

22.3 |

25.6 |

0.658 |

24.0 |

74.6 |

<0.001 |

|

Minimum meal frequency (6-23 months)** |

54.5 |

42.3 |

0.075 |

62.5 |

86.6 |

<0.001 |

|

Micronutrient powder use in the last six months? |

71.4 |

69.3 |

0.827 |

70.2 |

80.6 |

0.087 |

|

How do you prepare food with micronutrient powders? |

||||||

|

Cook with child’s food |

0 |

0 |

- |

5.8 |

0 |

0.034 |

|

Mix with cooked solid or semi-solid food |

88.4 |

99.0 |

0.006 |

84.6 |

100 |

<0.001 |

|

Mix with water |

11.6 |

1.1 |

0.006 |

9.6 |

0 |

0.003 |

*Proportion of children 6–23 months of age who received foods and beverages from five or more food groups during the previous day and night.

**Proportion of breastfed and non-breastfed children 6–23 months of age who received solid, semi-solid, or soft foods (but also including milk feeds for non-breastfed children) the minimum number of times or more.

At endline, 96% of homes in the peer-to-peer zones had established home gardens and 21.2% of children aged 6-23 months consumed vegetables and/or fruits at endline compared to 7.5% at baseline. After receiving training on the importance of having animal source foods to promote child growth and development, many peers adopted animal rearing practices to provide households with access to protein as well as organic manure for their home gardens. Saving groups allowed members to contribute a small amount of money every week and training was given on bookkeeping and saving financial resources. For example, in Gatsibo district, peer-to-peer beneficiaries created a saving groups composed of 25 members where each member contributed RWF 200 (£0.16) each week to make a total of RWF 5000 (£4.11), enough to buy small domestic animals for two members.

The endline survey results also indicated that 100% of intervention households reported effectively boiling their water for drinking compared to only 41% of control households. Household reported use of improved toilet facilities improved from 47% at baseline to 89% at endline in the intervention areas. Ninety-five percent of respondents in the intervention groups reported washing their hands with clean water and soap at three out of five critical handwashing moments, compared to only 45% of those in the control groups, indicating that the model may have had an impact on improving reported hygiene practices in homes.

The results of the endline survey indicated that, for the majority of respondents, fathers supported child and family nutrition in their household and accompanied their spouses for antenatal check-ups four times during pregnancy. The fathers’ prioritisation of their children’s nutrition was indicated by a large increase in the reporting of fathers allocating funds to buy food from 59% to 82% in the intervention villages. The ‘meaningful support’ of husbands towards nutrition for their lactating and pregnant wives increased to 87% (endline) from 51% (baseline), including the provision of animal source foods. Meaningful support was measured by the level of attendance of husbands to antenatal visits which included nutrition counselling.

The engagement and empowerment of community members within the design of the peer-to-peer intervention showed that he/she can be a positive agent of change in the community. For instance, Monique Muhawenimana, one of the peer supporters in Nyamagabe District noted, “I was happy to be selected as a peer. Since we have been involved throughout the process, I feel confident and empowered to help my fellow mothers to prepare nutritious food for their children like how have been doing for my children. I will continue to be an important member of the community even after the project phase out.”

Challenges

The peer-to-peer model was a new approach in Rwanda and it took some time for the partners to understand and embrace it. This was addressed through consistent engagement and trainings.

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged the implementation of the peer-to-peer approach due to the restrictions placed on gatherings and home visits. In-person interaction between peer supporters and non-doer peers was reduced depending on COVID-19 case numbers in the country. The use of phone-based messaging, including voice messages, WhatsApp messages and some peers using video recordings, bridged the gap in the absence of home visits as network connectivity is widely good throughout the country. Utilising mobile phones for optimal MIYCN advice was found to be acceptable and beneficial in the community, as was the advice given around selecting foods that were available and affordable to households according to their socio-economic status.

Conclusion

Human centered design approaches that apply insights and evidence from behavioural sciences provide a promising approach to influencing the behaviours and practices of parents and caregivers. The peer-to-peer approach worked well in this context and the regular support structure promoted positive behaviour change.

The endline results suggest that peer-to-peer activities contributed to improved infant and young child feeding and hygiene practices for households in five districts of Rwanda in a way that communication and education campaigns have not. The approach created ownership and empowered parents and communities to plan and address issues around malnutrition with key problem-solving and socio-economic competencies, even in the context of a pandemic. Continuous monitoring, evaluation, supervision, and refresher training were required to keep the peer supporters updated especially during the project’s infancy. Looking ahead, UNICEF has handed over the peer-to-peer model to the district leadership and National Child Development Agency for a proposed scale-up plan that considers the specific challenges faced in each district.

For more information, please contact Annet Birungi at abiringi@unicef.org

References

Birungi A, Koita Y, Roopnaraine T et al (2022) Behavioural drivers of suboptimal maternal and child feeding practices in Rwanda: An anthropological study. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 19, e13420. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13420

Birungi A, Limwame K, Rwodzi D et al (2021) A risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) response to support maternal, infant and young child nutrition in the context of COVID-19 in Rwanda. Field Exchange 65, May 2021. p46. www.ennonline.net/fex/65/covid19rwanda

Dusingizimana T, Weber J, Ramilan T et al (2021) A mixed-methods study of factors influencing access to and use of micronutrient powders in Rwanda. Global Health Science and Practice, 9, 2, p274-285. https://www.ghspjournal.org/content/9/2/274

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR), Rwanda Ministry of Health (MOH) and ICF (2021) Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2019-20 Final Report. Kigali, Rwanda, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

Rwanda Ministry of Health and Rwanda Biomedical Centre (n.d.) Rwanda 1000 days’ campaign assessment report (not available in print).