Conducting situation analysis as a first step to improve young children’s diets: examples from Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe

|

Key messages:

|

Introduction

In 2018 and 2019, as part of a broader programme to improve the quality of diets during the complementary feeding period in East and South Africa, 10 countries in the region undertook extensive country-level situation analyses that fed into a broader landscape analysis to provide key learnings and understandings about the barriers and enablers to improving the diets of young children.

Across the region, the country-level analyses allowed the identification of gaps faced by caregivers in providing their children with an optimum diet to support growth and development to their full potential. This provided the basis for refining, adapting and contextualising the complementary feeding Action Framework for improving the diets of young children aged 6–23 months according to individual country context.

This article illustrates the process and its outcomes using examples from three countries – Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe – and provides a strong illustration of actions that can be implemented in a concrete way as a result of conducting such an analysis.

The process

In each country, the process of conducting the situation analysis started with a consultative workshop. Under the leadership of the respective government ministerial departments – health, nutrition, agriculture and water – representatives from a wide range of agencies, civil society organisations, international non-government organisations and academia gathered to reflect on the Action Framework depicted in the programming guidance (UNICEF, 2020).

Over several days, the participants in each country took part in a series of thematic and sectoral discussions on the current state of young children’s diets in their respective context, based on existing situation analyses highlighting the drivers and barriers to young children’s optimum diets. Following this exercise, they identified strategic actions to be delivered through the four systems (health; water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH); food; and social protection) and at different levels, thus adapting the Action Framework to their respective contexts.

As a result of the process, each country implemented agreed actions that followed a systems approach and ensured the building of community resilience to accommodate the changing and volatile context, i.e. the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic amid pre-existing high poverty. The key results from this process in Ethiopia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe are described in the sections below.

Ethiopia

Nardos Birru is a Nutrition Specialist at UNICEF Ethiopia.

Charity Zvandaziva is a Nutrition Specialist responsible for Maternal, Infant and Child Nutrition at the UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO).

Hiwot Darsene is the National Nutrition Programme Coordinator at the Ministry of Health, Ethiopia.

Arnaud Laillou is a Regional Nutrition Specialist at the UNICEF West and Central Africa Regional Office (WCARO).

Ramadhani Abdallah Noor is a Nutrition Manager at UNICEF Ethiopia.

Stanley Chitekwe is the Chief of Nutrition at UNICEF Ethiopia.

We would like to thank the Ministry of Health (Ethiopia) and all participants, including government sector offices, partners and academia, for their commitment and contribution to the development of a child diets Action Framework for Ethiopia. We extend out thanks to GAIN for collaborating with UNICEF in the adaptation process. We would also like to acknowledge the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) for their funding support.

Findings from the child diets landscape analysis

The complementary feeding landscape analysis reviewed the national strategy and policies across four sectors (health, agriculture, social protection and WASH) to identify how they supported different aspects of complementary feeding and what good practices and opportunities there were for improvement. For each of the four sectors, the review found little or no reference to young children’s diets.

One of the main barriers identified for mothers to adopt age-appropriate complementary feeding practices was inadequate access to nutritious and safe foods as a result of absolute poverty, lack of purchasing power at the household level, and lack of market-level availability of diverse foods in pastoralist, remote and drought-prone areas.

A recent study showed that, although global food production increased in Ethiopia between 2011 and 2015, this growth was primarily within the cereal sector and at the expense of other food groups, which led to a decrease in production diversity (Baye et al, 2019). The scarcity of food transformation technologies and poor market linkages has further limited the availability of diverse food for children aged 6–23 months. A Fill the Nutrient Gap analysis1 conducted by the World Food Programme revealed that a nutritious diet for this age group would be four times more expensive than an energy-only diet, reiterating the need for strategies and actions geared towards increasing household purchasing power and the availability and affordability of nutritious foods. The lack of knowledge of caregivers and communities, compounded by cultural and religious beliefs, were additional challenges to diffusing age-appropriate infant and young child feeding (IYCF) key messages (Ethiopian Public Health Institute and the World Food Programme, 2021).

Identification of strategic actions

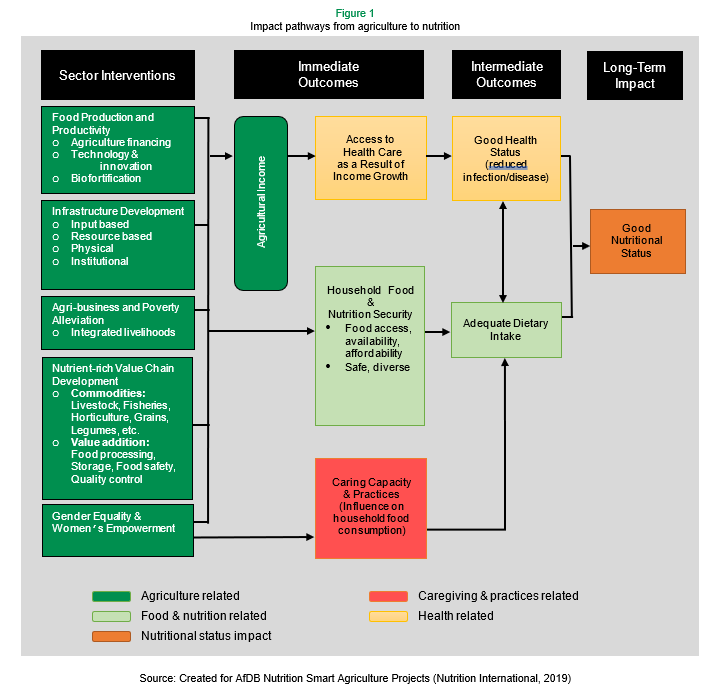

Following the review of the landscape analysis, participants delved into the barriers and bottlenecks to child diets in different contexts and across systems. Thereafter, the workshop participants identified strategic actions at the policy and institutional levels to be implemented through each of the four systems, according to the Action Framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Strategic actions identified to improve young children’s diets in Ethiopia

Workshop participants found that this exercise fostered productive multisectoral discussion and exchange, which was considered a positive outcome of this process.

A key recommendation from the workshop was the need to engage with the private sector. Considering the increasing production and marketing of commercial complementary foods in the country, participants believed there was a need to increase knowledge and common understanding among all stakeholders (including caregivers, communities and the private sector) towards promoting the production and consumption of nutrient-dense complementary foods. The private sector delivers health, WASH and nutrition services and products alongside the government. Strengthening partnerships and working together with the private sector would help ensure the appropriate products and services are delivered to children aged 6–23 months.

To promote diets that are of appropriate nutritional value, locally available and affordable for children aged 6–23 months, it was recommended to develop context-specific food recipes. UNICEF, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, took the lead to address this, and the initiative began by conducting a field assessment to identify locally available foods and examine eating habits of communities. The findings will inform recipes to be produced for Oromia, Amhara, Afar, Somali, Gambela and the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples (SNNP) and Sidama regions.

Cultural and religious beliefs play a significant role in driving IYCF practices. It was found that, without the involvement of religious and clan leaders and community volunteers in existing nutrition programmes, it would remain difficult to improve children’s diets and the uptake of nutrition services. Improving the nutrition literacy of these key community members was therefore included as crucial intervention. As a result, UNICEF has supported the government to develop orientation manuals for religious leaders, which are currently under review for endorsement.

Building on the outcomes of adapting the Action Framework at a national level, and considering the heterogeneity of the country, UNICEF has begun replicating similar consultations at the sub-national level to understand the different contexts and develop locally appropriate actions.

Tanzania

Tuzie Edwin Ndekia is a Nutrition Officer responsible for Early Childhood Nutrition at UNICEF Tanzania.

Charity Zvandaziva is a Nutrition Specialist responsible for Maternal, Infant and Child Nutrition at UNICEF ESARO.

Patrick Codija is the Chief of Nutrition at UNICEF Tanzania.

Kuda Mako-Mushaninga is Vice President for Scientific Affairs for the National Dairy Council.

Esther Nkuba is an Acting Director of Nutrition Education and Training at the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center.

Ruth Mkopi is a Senior Research Officer at the Tanzania Food and Nutrition Center.

Grace Moshi is an Acting Assistant Director of Nutrition Services at the Ministry of Health, Tanzania.

The authors are very grateful to the Global Thematic Fund for financing interventions to improve young children’s diets in Tanzania.

Findings from the landscape analysis

In 2021, as a result of recognising the importance of children’s diets as a key determinant of poor nutrition outcomes and their impacts on human capital in Tanzania, UNICEF Tanzania undertook two analyses. The Comprehensive Nutrient Gap Assessment analysis2 revealed that there were gaps in the consumption of iron and vitamin A during the complementary feeding period, as well as possible gaps in calcium, zinc and vitamin B12 (GAIN and UNICEF, 2021). The Children’s Diet Affordability Analysis (GAIN and UNICEF, 2019) indicated that a significant proportion of households struggled to afford nutritious foods to meet even half of the dietary requirements for iron for their children aged 6–23 months. The most affordable food sources recommended to fill the identified and potential micronutrient gaps included beef liver, chicken liver, small-dried fish, beef, eggs and dark green leafy vegetables.

Strategic actions and learnings

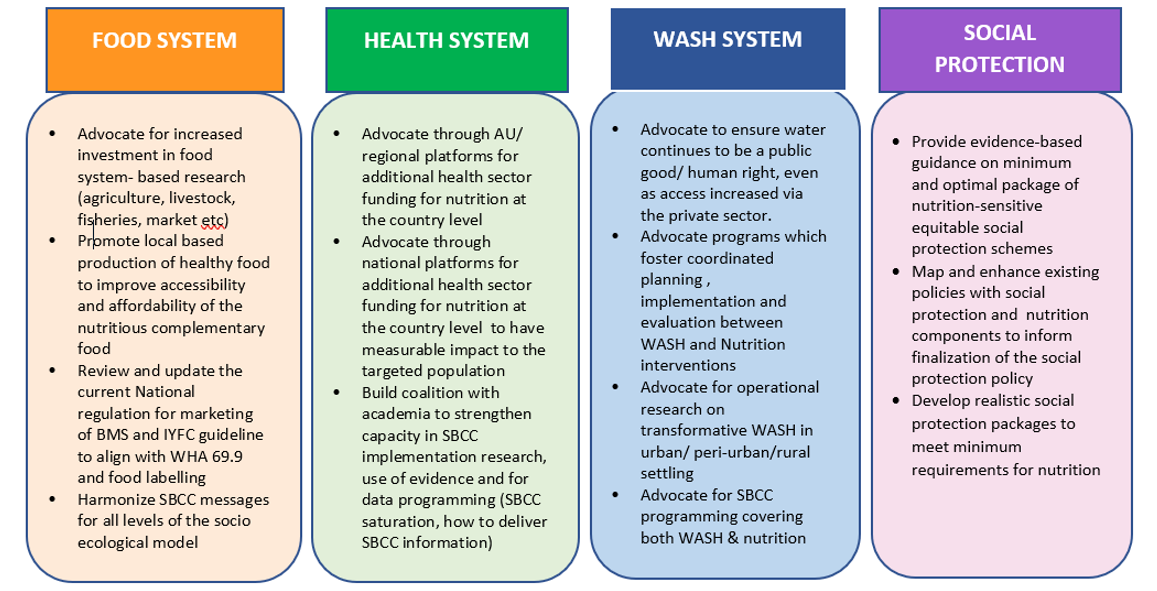

Technical consultations with key stakeholders from the government (ministries, departments and agencies), development partners (United Nations agencies and non-governmental organisations) and research institutes within each system (health, food, social protection and WASH) enabled them to define their policy priority actions and to highlight the relative contribution of each system to improving children’s diets in line with the country priority actions adopted at the regional level. Figure 2 summarises the key priority actions identified within each system.

Figure 2: Priority actions identified to improve young children’s diets in Tanzania

To ensure that this adapted Action Framework to improve children’s diets in Tanzania was translated into plans and action, priority actions were included within the second edition of the national multisectoral nutrition action plan (2021/22–2025/26). The goal to improve young children’s diets through increasing the proportion of children who consume a minimum acceptable diet from 30% to 50% by 2026 was among the commitments made by the Government of Tanzania during the Growth for Nutrition summit in Tokyo. This commitment will be monitored under the framework of the Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan.

Follow-up orientation sessions were also conducted for multisectoral teams at the regional and council level to enable them to customise the adapted complementary feeding Action Framework and to ensure the agreed actions were included in their comprehensive annual plans and budget. The actions that were prioritised for each sector will be monitored via the National Multisectoral Information System.

Next steps

The adapted Action Framework will be rolled out at the sub-national level (regional and local government authorities), with a target that over 90% (168) of Local Government Authorities in Tanzania will develop specific Action Frameworks to improve the diets of young children in their areas by June 2024.

Advocacy to ministerial permanent secretaries, department directors and nutrition focal persons will be conducted by the Prime Minister’s Office (which is responsible for providing leadership in nutrition coordination and for ensuring accountability and responsiveness across sectors), so that the agreed priority actions will be included within the plans and budgets of the four sectors. The Multisectoral Nutrition Action Plan Technical Working Groups will also ensure that agreed priority actions are part of both the strategic plans and the annual sector plans.

An accountability framework will be developed to monitor and document the implementation of priority actions at both sub-national and national levels as part of the existing Multisectoral Nutrition Information System. An Integrated Monitoring And Evaluation System will be the core system for collecting, analysing and reporting local and regional nutrition and related data, although there is a need to review and refine it to ensure the inclusion/capture of indicators from the other key sectors responsible for delivering the priority actions.

Zimbabwe

Dexter Chagwena is a Nutrition Consultant at UNICEF Zimbabwe.

Kudzai Mukudoka is a Nutrition Specialist at UNICEF Zimbabwe.

Kingstone Mujeyi is an Agriculture and Food Systems Specialist at University of Zimbabwe.

This article documents work conducted under a UNICEF nutrition and resilience programme implemented in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and partners in the Zimbabwe Resilience Building Fund Project (ZRBF). The ZRBF was implemented under the leadership of the Ministry of Lands, Agriculture, Fisheries, Water, Climate and Rural Development and the Ministry of Health and Child Care. The programme was funded by the European Union.

Programme description

A landscape analysis consultation was conducted in 2019 in Zimbabwe focusing on 18 districts where UNICEF was implementing the Zimbabwe Resilience Building Fund (ZRBF) programme, an integrated nutrition and resilience programme to improve complementary feeding practices among caregivers of young children aged 6–23 months. The landscape analysis consisted of formative research and a qualitative case study, which utilised a documentary analysis, an analysis of project monitoring indicators and a multi-stakeholder learning workshop and process evaluation analysis. The results of the landscape analysis were used to tailor ZRBF programme interventions to optimise positive impacts on young children’s diets, in conjunction with the adaptation and application of the complementary feeding Action Framework to the local context using a “systems thinking approach”. Integrated programming through the different systems – health, WASH, education, social protection and food – was coordinated through the multisectoral food and nutrition security committees (FNSCs) at district, ward and village level.

Programme implementation utilised the “care group model” – a community-level platform designed to promote optimal complementary feeding practices and related behaviours – to support recommended nutrition behaviours in target communities. Seven key behaviours were promoted to improve complementary feeding of young children and related facilitating actions, including improved handwashing by caregivers, household production and the promotion of diverse and underutilised nutritious food varieties. Other key approaches of the integrated ZRBF programme were contextualised social behaviour change and strengthening of local foods systems through the integration of nutrition-sensitive resilient food systems into value chains. Capacity building of multisectoral stakeholders on strengthening local food systems and the delivery of integrated nutrition-sensitive actions through different sectors were conducted through training, mentorship and assessments of the community food systems landscape and food environment.

The programme aimed to increase the capacity of at-risk communities to protect their development gains and achieve household and community resilience in the face of shocks and stresses. Since the nutrition actions were introduced as part of an existing resilience building programme, sequencing and layering of nutrition interventions on food security, resilience building and livelihoods interventions was prioritised with the aim of improving the diets of children from vulnerable households.

Programme outcomes

The integrated nutrition and resilience intervention was successfully implemented in all 18 districts despite differences in the way interventions were adopted between districts. Through a case-control evaluation, improvements on children’s diet quality were observed in target communities compared to similar communities not targeted by the ZRBF project. Caregivers in the targeted communities were three times more likely to offer children aged 6–23 months timely, adequate and diverse complementary feeding with continued breastfeeding for two years and beyond (OR 3.88 CI: 2.28-6.60; p<0.01) (Matsungo et al, 2022).

Strong partnerships between stakeholders facilitated effective integration of actions across sectors. In the 14 districts where stakeholder partnerships and sector collaboration were effective, nutrition actions were quickly delivered to communities, allowing wider coverage and adoption of recommended nutrition behaviours. In the remaining four districts, collaboration between stakeholders was a challenge, hindering the delivery of integrated actions and resulting in poor coverage of programme interventions.

Strong partnerships between stakeholders facilitated effective integration of actions across sectors. In the 14 districts where stakeholder partnerships and sector collaboration were effective, nutrition actions were quickly delivered to communities, allowing wider coverage and adoption of recommended nutrition behaviours. In the remaining four districts, collaboration between stakeholders was a challenge, hindering the delivery of integrated actions and resulting in poor coverage of programme interventions.

Learnings

The systems thinking approach proved effective in advancing actions to improve complementary feeding for young children within the resilience programme, as well as for the adaptation of the Action Framework for improving children’s diets. Strong government leadership, especially at sub-national level, was found to be key to the successful implementation of the Action Framework.

The programme provided key insights on factors that are key to implementing the Action Framework in resource-limited settings. Social and behaviour change communication focused on knowledge alone was not effective in improving children’s diets, even in the presence of complementary activities where production of diverse foods increased. Practical approaches or “learning by doing” were found to be more useful in changing behaviours. Resilience building interventions – including income generation, savings and loans associations, the production of more diverse and resilient crops and increasing market linkages – supported improved complementary feeding. In addition, community leaders played a key role in the success of the Action Framework delivered through various sectors.

Leveraging the nutrition-sensitive resilience building project (which was adequately funded) and utilising existing government structures allowed easy adaptation of the Action Framework for improving children’s diets, an approach that could be taken up by other low-income countries.

Conclusion

The three examples featured here show that an appropriate analysis of the situation and the use of the UNICEF Action Framework as a tool to help identify strategic actions can contribute to improving the diets of young children at the national level. Ethiopia and Tanzania have demonstrated that nationally led workshops result in policy changes and in a strong commitment to improving young children’s diets. In the case of Zimbabwe, the multi-system approach was complemented by the building of community resilience, and has the potential to lead to concrete changes and the creation of a positive environment to support long-term changes to improve young children’s diets.

For more information regarding the Ethiopia case study, please contact Nardos Birru at nbirru@unicef.org.

For more information regarding the Tanzania case study, please contact Tuzie Ndekia at tedwin@unicef.org.

For more information regarding the Zimbabwe case study, please contact Dexter Chagwena at dchagwena@unicef.org.

References

Baye K, Hirvonen K, Dereje M et al(2019) Energy and nutrient production in Ethiopia, 2011–2015: Implications to supporting healthy diets and food systems. PLoS ONE, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213182

Ethiopian Public Health Institute and the World Food Programme (2021) Fill the Nutrient Gap, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Public Health Institute and the World Food Programme. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000130144/download/

GAIN and UNICEF (2019) Affordability of Nutritious Complementary Foods in Tanzania. Geneva, Switzerland: GAIN. https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/gain-unicef-rising-project-affordability-of-nutritious-complementary-foods-in-tanzania-2019.pdf

GAIN and UNICEF (2021) Comprehensive Nutrient Gap Assessment (CONGA): Micronutrient Gaps During the Complementary Feeding Period in Tanzania. Geneva, Switzerland: GAIN. https://www.gainhealth.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/comprehensive-nutrient-gap-assessment-conga-micronutrient-gaps-during-the-complementary-feeding-period-in-tanzania.pdf

Matsungo T, Kamazizwa F, Mavhudzi T et al (2022) ZRBF The Care Group Approach, Infant and Young Child Feeding, Dietary Diversity and WASH Behaviours in Rural Zimbabwe: A Case-Control Study. ZRBF Learning and Process Evaluation Manuscript (in preparation).

UNICEF (2020) Improving Young Children’s Diets During the Complementary Feeding Period: UNICEF Programming Guidance. New York: UNICEF.

1 The World Food Programme’s Fill the Nutrient Gap tool analyses the nutrition situation in a country and identifies barriers to accessing healthy diets, platforms for reaching nutritionally vulnerable groups in the population and opportunities for policy and programme interventions to improve access to nutritious foods through multiple sectors, including agriculture, health, social protection and education.

2 This approach provides guidance on how to use various types of existing evidence to assess the public health significance of nutrient gaps in a given population, as well as the best food sources for those nutrients.