Creating a national nutrition information platform: Learnings from Bangladesh

Kimberly Rambaud Lessons Learned Advisor at ‘Capacity for Nutrition – National Information Platforms for Nutrition’ Global Coordination, GIZ Belgium

Heather Ohly Nutrition Researcher at N4D

Barbara Baille Nutrition Advisor at ‘Capacity for Nutrition – National Information Platforms for Nutrition’ Global Coordination, GIZ Belgium

What we know: Since 2015, the European Union has been supporting countries to create national multi-sectoral, country-led, and country-owned information platforms for nutrition known as National Information Platforms for Nutrition (NIPN). A rigorous and independent study on the performance and progress of the NIPN initiative was conducted in 2022.

What this adds: The authors reflect on the specifics identified by the evaluation that led to the closure of the project in Bangladesh. While the project was seen as relevant, it lacked coherence and effectiveness and was not sustainable. The short duration and many challenges faced by NIPN Bangladesh did not prepare the ground for impact. Several interesting outcomes were observed, such as the increased demand for robust data, evidence, and analysis on nutrition to inform policy development. Overall, the study highlighted the complexity of multi-sectoral projects and the need for genuine stakeholder engagement throughout.

Background

The NIPN initiative was launched by the European Union in 2015 to support partner countries who are part of the global Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement. SUN countries have committed to delivering evidence-based programmes and interventions to improve human nutrition in their progress toward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goal 2: to ‘end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.’

The driving objective of NIPN is to create national multi-sectoral, country-led, and country-owned information platforms for nutrition. Each platform is intended to strengthen national capacities in nutrition data analysis to ultimately bolster the inclusion of evidence-based nutrition recommendations to better inform decision makers in the areas of policy, programming, and investment for nutrition.

Starting in 2018, nine countries took part in the NIPN Phase 1 initiative: Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire (N’dri et al., 2022), Ethiopia, Guatemala, Kenya, Lao PDR, Niger, and Uganda. Between 2020 and 2022, eight countries transitioned to Phase 2 of the NIPN project, while NIPN Bangladesh closed in February 2022. The following year, in 2023, Zambia began implementing NIPN, bringing the number of countries back to nine at the time the current article was written.

A global coordination team, managed by Capacity for Nutrition (C4N ), coordinates the nine NIPN projects at global level. In 2022, C4N-NIPN commissioned the group N4D to conduct a rigorous and independent study on the performance and progress of the NIPN initiative. The study included two country deep-dives, on Kenya and Niger, and a full audit of the closed Bangladesh programme. This article focuses on the learnings from NIPN Bangladesh. It aims to detail the lessons learned from the factors that led to the closure of the programme and to provide specific recommendations to support future design and implementation of successful national nutrition information systems.

Methodology

N4D used the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) criteria to assess the performance of the NIPN platform in Bangladesh in terms of relevance, coherence, effectiveness, impact, and sustainability. The study was driven by the research questions set out in Box 1. To answer each research question, the evaluators developed a set of judgement criteria/indicators that they explored either through analysis of secondary data (desk review of key strategic documents and data related to NIPN concepts and activities: theory of change, data landscape analysis and annual reports), or through the collection and analysis of primary data (interviews with NIPN stakeholders and partners). In their approach, the evaluators assessed the relevance of NIPN design at country and global levels to meet both the needs of target stakeholders and the aims and objectives of the initiative.

Box 1: Research questions for the evaluation of NIPN BangladeshRelevance How relevant was the NIPN approach in driving optimal policy and programme approaches to address malnutrition? Coherence To what extent was NIPN coordinating and collaborating with relevant initiatives and actors to achieve results? Effectiveness To what degree has NIPN achieved its intended results (direct outcomes)? Impact To what extent have NIPN activities implemented contributed to impact (indirect outcomes)? Sustainability To what extent have results been sustained to strengthen national capacities for evidence-based nutrition policy and programming? |

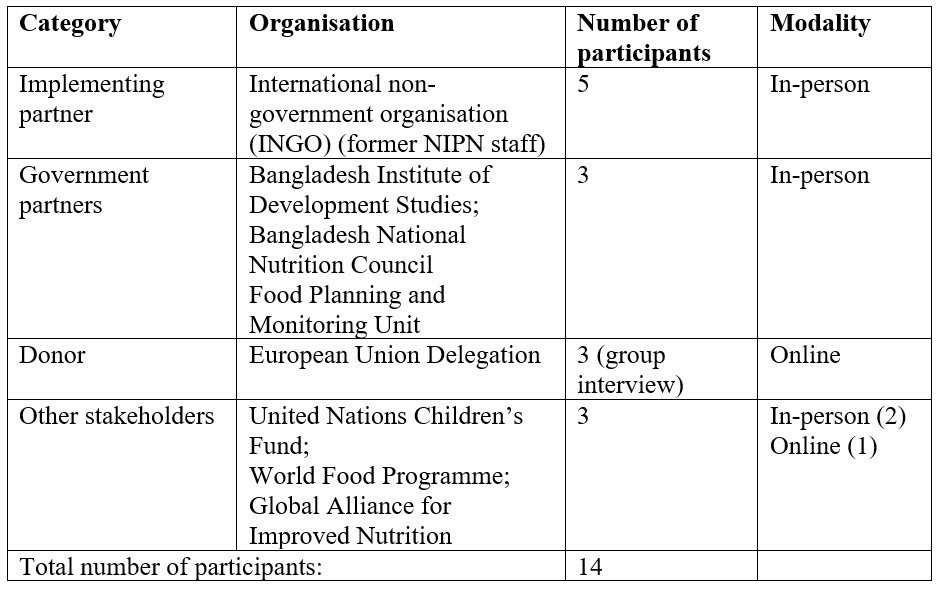

In April 2023, the N4D nutrition researcher interviewed 14 stakeholders and partners in 12 interviews (Table 1). Interview findings were triangulated with the previously completed desk review.

Table 1: Summary of interviews

Findings

Based on the desk review and in-depth interviews, the findings are presented in line with the five OECD-DAC criteria.

Relevance

There was unanimity among those interviewed that NIPN was a relevant initiative for Bangladesh. The nutrition data landscape is very fragmented, with a lack of coordination between sectors and within government. Additionally, data and information have historically flowed from programmes to donors individually and there has been no national information system to track progress. As such, respondents agreed that NIPN as a concept could add value to support the strengthening of data systems and using data to promote government-owned, multi-sectoral nutrition policies and programmes.

However, analysis showed that the method of implementation in Bangladesh was not appropriate for the national context nor responsive to the needs of the government and other key stakeholders. The donor-selected institutional arrangements for NIPN Bangladesh, with an INGO as the primary contract holder, was seen as less than optimal. Most respondents felt that the Government of Bangladesh should have had ownership of the initiative. Bangladesh is the only country in which NIPN was implemented by an INGO. The government partners and other national stakeholders were not invited to contribute to the decision-making process when contracts were awarded. This led to a feeling of lack of transparency and communication in the early stages of setting up NIPN Bangladesh.

Coherence

Multi-stakeholder projects are inherently complex, with many partners, stakeholders, and multi-sectoral committees. In Bangladesh, the evaluation showed that the inception period of six months planned to set up a NIPN platform was too optimistic given the complexity of the institutional landscape. Key activities such as reaching consensus on the institutional structure and developing the multi-sectoral committees took much longer than expected. In the end, it took around 18 months for the project set-up to be completed. Participants consistently referred to the lack of progress during the first 12–18 months of the project, which they felt was due to poor management, poor communication, and delays with approvals. Progress was particularly slow because the main guarantor was an INGO, which was unable to efficiently engage government officials. Due to the multifaceted nature of NIPN, the project was a challenge to coordinate, resulting in significant delays from the start and throughout. Key strategic documents lacked comprehensive planning and were insufficiently detailed, resulting in incoherent engagement across stakeholders.

Changes in leadership also created challenges with internal coherence. During Phase 1 (2018–2022), covering the majority of the project duration, three different technical directors for NIPN Bangladesh were hired, with the position left vacant in between appointments. Respondents highlighted that these three leaders had vastly different interpersonal qualities, experience, and leadership skills, which required adjustment periods with each change. Interpersonal challenges between one of the NIPN technical directors and the INGO Country Director also resulted in barriers to trust and rapport building, and ultimately internal coherence.

Effectiveness

After the delays, NIPN Bangladesh became fully operational in the second half of 2019. The first policy advisory committee meeting took place in September 2019. This is the first step in the NIPN approach, whereby the NIPN partners and stakeholders convene and discuss the most pressing nutrition issues and key governmental priorities in the country. This first meeting generated a series of policy questions for the data analysis unit to investigate. However, several respondents noted that the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, which was the government partner responsible for formulating and validating policy questions, was not suitable to host the policy component in the long term. As such, NIPN Bangladesh missed out on opportunities to provide valuable inputs to institutional stakeholders and to demonstrate its added value as a key player in the multi-stakeholder dialogue.

Despite challenges with the policy question formulation, NIPN Bangladesh made a concerted effort to generate evidence on national nutrition issues to support the country in strengthening national nutrition policies and interventions. It conducted 11 relevant studies; by the end of Phase 1, nine of these were in final or draft form.

Capacity-building activities were an important element for the effectiveness of NIPN Bangladesh. The platform demonstrated the ability to adjust to hybrid and remote formats during the ever-changing COVID-19 period, managing to train over 200 government stakeholders across 17 ministries. However, different members of staff were nominated to attend each course (presumably in an effort to ensure fairness), which limited the ability of individuals to complete the whole package of training. This ultimately resulted in fragmented coverage of skills development. Respondents also felt that institutional capacity strengthening had been insufficient. Overall, capacity development was viewed as impressive and well received, but inadequate to meet the needs of establishing a NIPN.

The hosting INGO and Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics had reached a formal agreement to establish a data repository. A server was purchased and data guidelines were developed, alongside procedures for managing and using data within the repository. Interviews revealed that no respondents knew about the status or whereabouts of the data repository. This is suggestive of a serious lack of accountability in regard to a crucial component of NIPN and a major gap in the effectiveness of the NIPN Bangladesh set-up.

Impact

Although the short duration and many challenges faced by NIPN Bangladesh were not conducive to achieving impact, respondents noted several interesting outcomes from the programme. For instance, NIPN increased demand for robust data, evidence, and analysis on nutrition to inform policy development. The studies conducted by NIPN Bangladesh were used by several stakeholders, including government and non-government partners such as the Food Planning and Monitoring Unit under the Ministry of Food and the Bangladesh National Nutrition Council.

Sustainability

NIPN Bangladesh attempted to develop a sustainability plan, but it was never finalised nor operationalised. This suggests that sustainability was considered at a late stage. Opportunities for longer-term impacts were therefore likely missed.

In addition, there was no formal consultation to inform NIPN partners and stakeholders of the reasons behind the discontinuation of the platform, nor was there an opportunity for course correction once they were informed. Finally, a cost extension was granted to allow for proper programme closure. Despite it being planned for nine months, the extension period was reduced to two months, which meant the team was not able to devise an exit strategy to tie up loose ends or properly conclude the project.

Lessons learned

Multi-sector nutrition information projects can strengthen collaboration across sectors and add value by delivering evidence-based recommendations to nutrition policy-making processes. The audit of NIPN Bangladesh provided useful lessons learned for C4N-NIPN, the European Union Delegation, and other interested parties that may want to use the experiences to support future programme design. The following lessons, derived from the findings provided above, aim to provide readers with concrete elements to consider when setting up and implementing similar programmes.

Appropriate institutional arrangements

The institutional arrangements of a NIPN are critical to its success and should empower national actors rather than international organisations. A robust context analysis during the NIPN scoping exercises can inform the different options. The experience of the NIPN in Bangladesh highlights the importance of optimal institutional arrangements and how they support the implementation and achievement of objectives. Without appropriate institutional arrangements, the NIPN’s ability to stimulate government interest and coordinate multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder input is severely restricted. This statement is also supported by the experience of other NIPN countries, where the financial support was directly awarded to national institutions during Phase 1 of the project (such as Kenya and Burkina Faso). In these countries, NIPN directors are civil servants who are affiliated to national institutions, illustrating government leadership and ownership.

Adaptation to context

NIPNs need adequate contextual analyses that are regularly updated and inform decision-making. The design of the NIPN in Bangladesh was aligned to the general strategy of NIPN. However, there was insufficient attention to the specific contextual risks that may cause delays. The design of NIPN Bangladesh should have included a comprehensive risk register with corresponding mitigating actions, so the achievement of outcomes would not be threatened.

Clear coordination strategy

An initiative that depends on effective coordination mechanisms and dialogue between implementing entities should have a clear coordination strategy.

Recommendations for nutrition information systems

The lessons learned from NIPN Bangladesh provide valuable insights for other NIPNs as well as other nutrition information systems more broadly. Building on the findings previously mentioned, respondents identified certain critical elements necessary for a NIPN, or other national nutrition information system, to be successful.

Ensure government leadership

Government leadership is a prerequisite to national ownership that will enable stronger coordination across ministries and other key national entities, and a position closer to the policy-making process. Embedding NIPNs within national systems allows the project to be developed in line with government ways of working. This does not guarantee success, but it can bypass the implementation challenges experienced in Bangladesh.

Transparency on contracting

Transparent processes via an open consultation process must take place to identify, filter, and secure partnerships with the most relevant stakeholders.

Human centred

The influence of human relationships on the uptake of an initiative should never be underestimated. Promoting open and regular communication is key.

Embed communications

A communications strategy should be designed based on stakeholder mapping to ensure effective reach to target audiences. It should be approved in the early stages and updated regularly.

Standard operating procedures

Clear and efficient processes and mechanisms, such as decision-making processes, must be set into place to promote clarity and accountability.

Capacity development

It is necessary to invest time in targeting and tailoring capacity development activities to the right audiences, rather than casting a wider net to reach many. Key individuals should be targeted to receive comprehensive training in their technical areas. Training of trainers should be prioritised to facilitate skill transference and scaling of skills.

Conclusion

The learnings from the Bangladesh evaluation can help inform and strengthen current and future iterations of NIPN. C4N-NIPN promotes and encourages the frank exchange of challenges from both a global level with partners and donors as well as peer-to-peer formats. Above all, NIPN Bangladesh highlighted the complexity of multi-sectoral projects and the need for genuine stakeholder engagement throughout.

For more information, please contact Kimberly Rambaud at Kimberly.rambaud@giz.de.

References

N’Dri F, Ake G, Mady R et al. (2022) Establishing an effective multi-sectoral nutrition information system in Ivory Coast. Field Exchange 68. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/68/nipncollaborationivorycoast

About This Article

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Kimberly Rambaud, Heather Ohly and Barbara Baille (2024). Creating a national nutrition information platform: Learnings from Bangladesh. Field Exchange 72. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25563471