Promoting infant and young child feeding in Lebanon: Lessons learned from programming

Lamis Jomaa Associate Professor at North Carolina Central University and Affiliate Associate Professor at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon

Kate Price Intern at the Humanitarian Health Initiative, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill (UNC)

Clara Hare-Grogg Intern at the Humanitarian Health Initiative, UNC

Astrid Klomp Former Nutrition and Health Coordinator at Action Against Hunger Spain (AAH), Lebanon

Aunchalee Palmquist Associate Professor of the Practice, Duke Global Health Institute

We would like to acknowledge the efforts of all AAH members who took part in the interviews and facilitated data collection. Thanks to Domanique Richards, from the Department of Nutrition Sciences at North Carolina Central University, for her support with the annotations for this article.

What we know: Lebanon, a country with one of the highest proportional refugee populations globally, is currently facing a multifaceted financial and health crisis. Despite the release of the Lebanon National Nutrition Strategy and Action Plan (2021–2026) and efforts by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and partners, challenges with the implementation and evaluation of infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programmes remain.

What this adds: AAH interviewees working in Lebanon outline environmental barriers to IYCF programming, suggestions to improve programming to support caregiver practices, and potential staff training tools that can be used to improve health and nutrition services. Further exploration of complementary feeding challenges is needed to fill the remaining knowledge gap, particularly in humanitarian and conflict settings, where the provision of safe, nutritious, and culturally appropriate complementary foods is key.

Background

In Lebanon, children continue to bear the brunt of one of the world’s worst economic crises. Among children aged under 2 years, 26% can be classified as severely food poor, with malnutrition posing a new threat to the health and development of infants and young children (UNICEF, 2023). Poor adherence to optimal IYCF practices is noted (Akik et al., 2017; Naja et al., 2023). Weak policy endorsements, poor implementation of baby-friendly hospital initiatives, and the strong influence of private industry that promotes the distribution and marketing of commercial milk formula, along with other cultural barriers, were all listed as obstacles to optimal IYCF practices in Lebanon and its neighbouring countries (Shaker-Berbari et al., 2021).

AAH has worked in Lebanon since 2006. Nutrition interventions, which have been incorporated into the overall response since 2012 (with increased attention from 2020 onwards), focus on promoting appropriate IYCF practices through knowledge sharing, one-on-one counselling, and group sessions. These were delivered by a multi-pronged staff intervention strategy at community level, with most interventions provided through home visits.

The aim of this study was to explore the challenges and opportunities faced by AAH community health workers and implementation team members in their promotion of appropriate IYCF practices among vulnerable Lebanese and Syrians in Lebanon. The study objectives were to examine the perceptions of programme workers regarding available tools, guidelines, and training, and to explore worker perceptions regarding existing opportunities and barriers to the promotion of IYCF in this context.

Study design

This qualitative study was facilitated through a collaborative effort between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Gillings Humanitarian Health Initiative (UNC-HHI), researchers from the Department of Nutrition Sciences at North Carolina Central University, and AAH Lebanon. Recruitment took place via purposive sampling, where a list of all current AAH Lebanon nutrition staff, as well as any health/nutrition staff who finished their contract within the last 2–3 months, was shared with researchers. Then, 13 potential voluntary interviewees were identified by the AAH health and nutrition coordinator, resulting in 12 interviewees responding. The positions covered were IYCF specialists (n=6), community nutrition officers (n=3), and managerial/supervisory staff (n=3). All interviewees had prior community-level experience and were national workers. Their years of service at AAH ranged from 1–8 years.

Semi-structured remote interviews were conducted from December 2022 to January 2023. Interviews were based on a topic guide that included questions about staff knowledge and skills, tools used to implement teaching interventions, gaps in resources, and what staff felt were biggest barriers to implementation of optimal IYCF counselling and education. Each UNC-HHI-trained interviewer followed the same structure with the same questions from the pre-approved topic guide. Interviews were 35–60 minutes long. Consent to record audio, clarify study aims, and obtain secondary verbal consent occurred at the beginning of each interview.

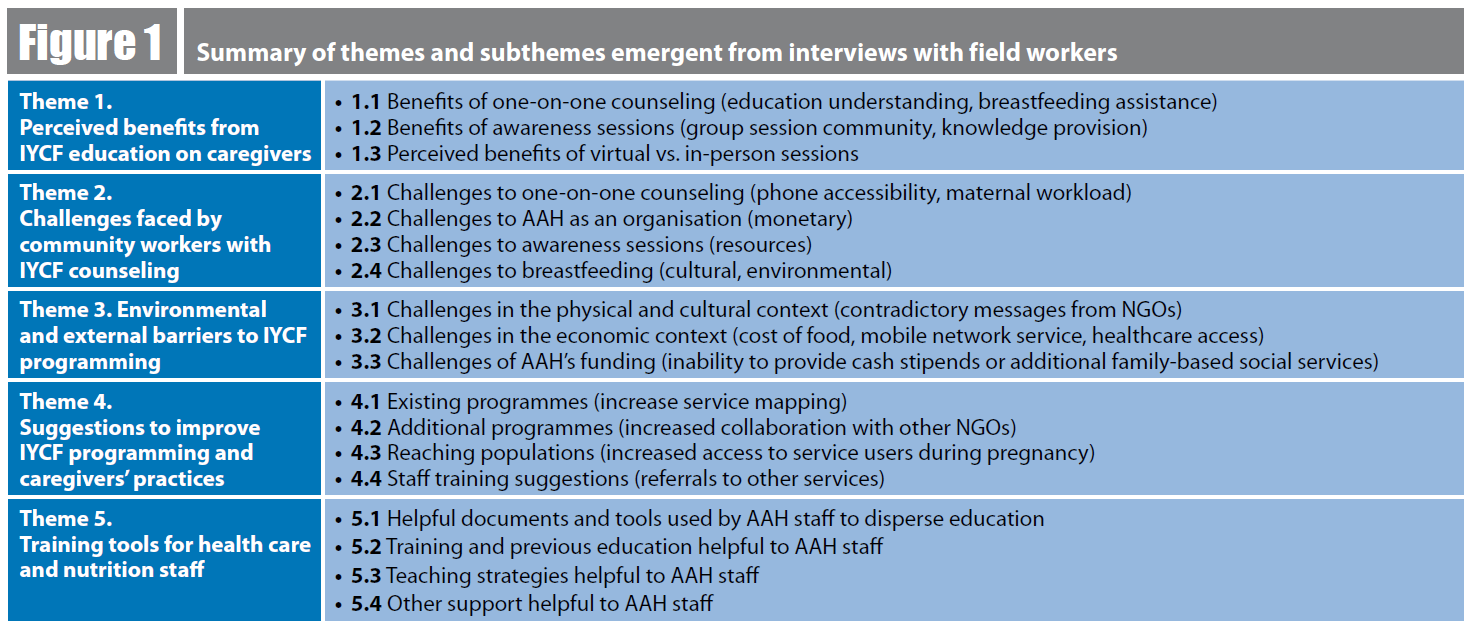

The UNC-HHI team created a preliminary coding frame for the first stage of analysis. Each research assistant coded 6 interviews for continuity and then checked several of their partner’s interviews to verify they used similar codes. Codes were grouped together under overarching themes and then organised into various sub-themes. The organisation of themes and sub-themes were refined through group discussion and are presented below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Summary of themes and subthemes emergent from interviews with field workers

AAH staff noted that one-on-one counselling and group sessions were particularly helpful for IYCF promotion. Counselling sessions improved understanding and gave staff opportunities to tailor intervention strategies to specific concerns, economic situations, and feeding misconceptions (theme 1). AAH IYCF specialists also felt that they could better assess mother and baby dyads in-person. The COVID-19 pandemic affected these in-person activities, but since restrictions have been lifted in-person interventions have resumed. However, the experience of conducting remote support during the pandemic was useful preparation in case of extraneous factors that may affect access – including conflict, which remains an imminent challenge faced in Lebanon.

In-person visits with added virtual messaging were considered the ideal mode for optimal IYCF promotion. This mixed modality of services allowed staff to assess the feeding and health-seeking behaviour of caregivers closely, while making sure that those who couldn’t attend sessions still had information communicated to them. The use of voice memos and photos through WhatsApp and other messaging services was also noted as advantageous by nutrition/health staff. Group sessions were also noted as positive, as staff saw an increased sense of community from shared experiences.

“… we see that the baby is drinking tea during breakfast. We advise them no, please don’t take tea with food, especially for the babies. So they say, yes. During follow up, we see that there is really a change. The baby is not drinking tea during breakfast, so there is really a change in thinking that makes sense…you see that the parents are changing their lifestyles, their beliefs.” – Interview 5

Challenges faced by community workers with IYCF counselling (theme 2) included phone accessibility issues affecting their ability to reach caregivers and schedule and/or conduct counselling services remotely, in addition to maternal workload and other competing demands that limit the ability to conduct counselling sessions. In addition, the lack of consistent and reliable internet services posed an issue in regard to people receiving voice memos. Many service users did not have reliable use of mobile phones due to financial instability, lack of stable mobile networks, or male partners in the house using the phone for work purposes.

“...the refugees won't have online resources available to them the whole time. Many of them do not even have cellular phones to use on daily basis. We cannot even call the beneficiary sometimes, so definitely being face to face with them in the field is way more practical. You can transmit the message much easier. We can provide ongoing questions and follow-up questions. So it's way easier to communicate back and forth.” – Interview 9

Interviewees also highlighted environmental and external barriers to IYCF programming (theme 3) that were related to the worsening economic circumstances in the country affecting food costs and the ability of service users to access food and other basic resources for their households. Cultural misperceptions and social practices that limited optimal breastfeeding practices from caregivers and/or affected their confidence in their ability to breastfeed their children were also noted as barriers. Tea remains one of the common beverages provided early, particularly among the Syrian refugee population in the country. Offering ultra-processed snacks and beverages to young children – i.e., sweetened juices and sodas – was another common practice highlighted by some interviewees. Reasons cited for early introduction of complementary foods include cultural beliefs that breastmilk alone becomes insufficient after 3–4 months, the perception that the child is old enough, and the onset of a new pregnancy (Nasreddine et al., 2012).

According to interviewees, service users often receive contradictory messages about nutritional guidance from different international organisations (like AAH) and certain local primary health care centres, where commercial milk formulas are often promoted by health professionals. Despite the release of strategies and policies to promote optimal IYCF practices, violations of the ‘WHO Code’ continue to be reported in this context (Shaker-Berbari et al., 2018; Mattar et al., 2023). There is a need to create a stronger enabling policy environment for breastfeeding that is free from commercial influence. In support of this, AAH positions itself within relevant coordination structures, such as the humanitarian nutrition sector and the national IYCF committee, and reports any violation of the law when this is observed. The organisation provides training to national staff and medical team members at primary health care facilities on ‘The Code’ and the Lebanese 47/2008 Law supporting breastfeeding.

Suggestions to improve existing programming varied among service providers (theme 4). AAH staff suggested a longer follow-up period and increased frequency of follow-ups to ensure programme effectiveness. They also expressed a desire for better coordination with primary health care centres and social services to offer psychosocial support and provide specialised services where needed. Increased service mapping, along with expanding interventions to include pregnant individuals, were also common suggestions. In addition, interviewees/staff suggested providing incentives like food parcels to retain families in AAH’s nutrition and IYCF programming.

With AAH implementing IYCF programming in certain areas of the country for the last 4 years, it is anecdotally noted that behavioural changes are slowly happening when programming is delivered within the same communities over a longer period. These promising results have led AAH to advocate for programming to continue beyond the 1-year project timeframe.

“I think we usually do our sessions within 2 weeks. I prefer if we could have another visit after 2 or 3 months to see if it was really a behavioural change or just a period and they changed during the period that you are visiting them.” – Interview 8

Furthermore, AAH staff highlighted the importance of getting more training on the use of various educational visuals and promotion tools to assist with their services, along with the engagement of community members as a source of peer-to-peer education (theme 5). AAH Lebanon continues to look at how staff training can be improved, specifically around complementary feeding, since the current training focuses heavily on breastfeeding promotion. Although the availability of trainers has been limited thus far, AAH continues to provide on-the-job training and supervision to improve the skills of staff through developments described below.

“I wish that I could have more training on the details of complementary feeding. For example, what can be given and what not? How much should be given to the child? If any of the food could cause an allergic reaction in the child, what are the signs, and how do we identify any risk on the child?” – Interview 3

What do these findings tell us?

This study utilised a diverse and well-trained team of researchers with national and international humanitarian experience. The standardisation of interviewing and probing methods, by trained interviewers, further increases our confidence in these findings. Nevertheless, sampling from a single international organisation does limit our ability to generalise these findings. Future research could also include interviews with service users (caregivers) to explore their perceptions and experiences. Using community perspectives to build interventions is essential to implement meaningful changes.

Environmental and economic factors were commonly cited as the biggest barriers to effective implementation of promotional IYCF sessions and their translation to behavioural change in the feeding practices of caregivers in this context. Most of the challenges raised by interviewees were focused on breastfeeding promotion, with less emphasis on challenges related to complementary feeding practices (beyond the ongoing economic hardships and limited access to food that households face). More programmatic considerations and research are needed to address knowledge gaps and needs for complementary feeding within high-risk, low-resource settings – particularly in humanitarian and conflict settings.

Since this study, new tools and training have been put in place by the organisation. Specifically, they have clarified the different roles of IYCF specialists and community nutrition officers: IYCF specialists now focus more on one-on-one counselling, with a special focus on breastfeeding promotion, while community nutrition officers now focus on providing supportive supervision for community mobilisers, who provide home group sessions. Anecdotal feedback suggests this change has improved staff confidence and enables AAH to better utilise resources to reach more children and their caregivers in Lebanon.

Community MUAC screening of both pregnant and breastfeeding women and children aged 6 months to five years was rolled out nationally in late 2022. AAH has integrated this into their programmes – thus referring women and children who are found to be malnourished to the nearest primary health care facility for follow-up.

Introducing joint IYCF and multi-purpose cash assistance has been strongly advocated for by AAH Lebanon as there is evidence that dietary outcomes improve when these two are combined (Global Nutrition Cluster, 2020). AAH has also changed its model for group sessions, as attendance was limited in the past. Now, community mobilisers are being trained and supervised to provide home group sessions within their local communities. Home sessions are considered a more organic form to implement group sessions, since transportation to and from a community location to health care sites remains a barrier in Lebanon. There is also now a greater understanding of the importance of male-led peer-support groups. In Nigeria, such programming encouraged all household members to utilise limited resources to ensure diverse diets (Atuman et al., 2023).

For more information, please contact Astrid Klomp at Astrid.Klomp1@alumni.lshtm.ac.uk.

References

Akik C, Ghattas H, Filteau S et al. (2017) Barriers to breastfeeding in Lebanon: A policy analysis. Journal of Public Health Policy, 38, 3, 314–326.

Atuman S, Langat O, Lellamo A et al. (2023) Father-to-father support groups in northern Nigeria: An emergency response initiative. https://www.ennonline.net/fex/70/father-to-father-support-groups-in-northern-nigeria

Global Nutrition Cluster (2020) Evidence and guidance note on the use of cash and voucher assistance for nutrition outcomes in emergencies. nutritioncluster.net.

Mattar L, Hassan H, Kalash N et al. (2023) Assessing the nutritional content and adequacy of food parcels among vulnerable Lebanese during a double crisis: COVID-19 pandemic and an economic meltdown. Public Health Nutrition, 26, 6, 1271–1283.

Naja F, Hwalla N, Chokor F et al. (2023) Infant and young child feeding practices in Lebanon: A cross-sectional national study. Public Health Nutrition, 26, 1, 143–159.

Nasreddine L, Zeidan M, Naja F et al. (2012) Complementary feeding in the MENA region: Practices and challenges. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases, 22, 10, 793–798.

Shaker-Berbari L, Ghattas H, Symon A et al. (2018) Infant and young child feeding in emergencies: Organisational policies and activities during the refugee crisis in Lebanon. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, 3, e12576.

Shaker-Berbari L, Qahoush Tyler V, Akik C et al. (2021) Predictors of complementary feeding practices among children aged 6–23 months in five countries in the Middle East and North Africa region. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 17, 4, e13223.

UNICEF (2023) Child Food Poverty: A Nutrition Crisis in Early Childhood in Lebanon. unicef.org

About This Article

Jump to section

Download & Citation

Reference this page

Lamis Jomaa, Kate Price, Clara Hare-Grogg, Astrid Klomp and Aunchalee Palmquist (2024). Promoting infant and young child feeding in Lebanon: Lessons learned from programming. Field Exchange Magazine 72. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25461115